The Iroquois Theater Fire

Dec 30, 1903

Fireproof Firetrap

Fireproof Firetrap

America's Worst Loss Of Life In A Single Building Fire.

Ahhh, Chicago! The Windy City! Home to The Cubs, Al Capone, John Belushi, and, of course, Ferris Bueller.

Chicago boasts one of the most colorful histories of any city in the U.S. and is every bit as loaded with history, drama and mystique as it's East Coast arch rival, New York City. In fact, when you get right down to it, The Windy City's history and legend just may be a scosh more colorful than The Big Apple's.

Wait...you didn't know New York was Chicago's arch-rival?

Oh yeah...A spirited, but one-sided rivalry began between these two legendary cities towards the end of the 19th Century, when Chicago finally edged past Philadelphia to become the second most populous city in the U.S. (A title the Windy City would hold until the mid 20th Century, when L.A snagged the #2 spot for themselves.). Second, I might add, only to New York. The good citizens of Chicago found that they did not like being 'Number 2' and most especially, didn't like being 'Number 2' behind The Big Apple.

New York, on the other hand, pretty much ignored the fact that they'd gained a brand new Arch-Rival...Go back in time and ask any Chicagoan from 1903 which city they considered their arch-rival, nemesis, and city to beat at all costs and they'll tell you, with little hesitation and a good bit of enthusiasm, 'New York'.

Go to New York and ask that very same question, however, and the answer won't be Chicago. In fact, New Yorkers really didn't, and indeed, still don't, consider themselves to even have a rival ...they pretty much knew, and indeed, know they're #1. Chicago wasn't even on their radar as a rival.

That fact did absolutely nothing to dispel The Windy City's desire to one-up The Big Apple, which is why, as soon as they snagged that #2 spot, Chicago began doing everything in their power to blow past New York in every possible category.

One of the categories they decided to try to one-up New York in was Theater. Which is kind of like your local high school football team deciding to take on the New York Jets.

Don't get me wrong here...Chicago had a pretty solid presence in Theater at the turn of the 20th century. The city was home to thirty-six theaters in 1903, but that was still just a fraction of the number of playhouses in New York. The New York theater scene had blown past The Windy City's theater scene decades earlier and was still pulling away steadily.

After all, in the U.S. the New York Theater scene pretty much was (And indeed, still is) THE THEATER. Broadway had, by then, become...

'BROADWAY!!'

...And All Things Theater looked towards The Big Apple for their cue.

Needless to say, this made the New York theater scene hard, if not impossible, to top. Chicago, however, was not only going to try to beat The Big Apple at their own game, they were going to try to do it with a single theater...a Megatheater, encompassing every possible modern luxury feature and safety technology known to man, to be called The Iroquois Theater.

Unfortunately, while they were at it, they managed to surpass New York, and every city in the U.S. in one category that they didn't even want to compete in. When the Iroquois Theater burned with an over-capacity house attending a matinee performance of Mr Bluebeard on December 30th, 1903, it resulted in 602 deaths...The highest death toll ever recorded in a structure fire in the U.S, a record that stands to this day.

And yes, you read that right. Just over six hundred people...the majority of them women and children...died on that frigid December afternoon, and the events that led to their deaths began in the spring of 1903, when a pair of enterprising gents named Will J. Davis and Harry Powers bought a couple of lots near Randolph and Dearborn Streets, in Chicago's already legendary 'Loop' (named after the system of elevated trains...the legendary 'El'...that served Chicago's main business district), with intent to erect the afore-noted theater to end all theaters there.

It's a good bet that these two gentlemen needed some backing from somewhere in order to tackle such a huge task...not only financial backing, but professional backing as well, the latter to ensure that major plays (The forerunner of today's first-run blockbusters) were performed on their theater's stage.

Enter The Theatrical Trust.

As I noted in my post about the Brooklyn Theater Fire, several theaters would be owned by a single corporate entity, just as movie theaters are today. Think Regal Cinema's, Or, maybe, kinda think Regal Cinemas, because, if you go by percentage of the nation's theaters owned rather than hard numbers, the New York based Theatrical Trust...the syndicate that owned and controlled the vast majority of the nation's major theaters in the late 19th/early 20th Century...made Regal look like a small town business owner.

I'm not sure if Will Davis and Harry Powers approached the Theatrical Trust to inquire about backing, or if The Trust, with it's pulse on all facets of the theater industry, heard of the plans for a new theater and contacted them with an offer to provide financial and professional backing (And to provide themselves with yet another source of profit), or if, possibly the plan to build the Iroquois was a collaboration between the team of Davis and Powers and The Trust from the outset, but whichever way that collaboration came to be, the Iroquois ended up under the collective thumbs of the Theatrical Trust.

Wait, Rob, you ask...just what was this 'Theatrical Trust' of which you speak?

That organization's story could fill an entire book all it's own, much less a blog post, but I'll try to hit the high points here. The Theatrical Trust was run by a Good-Cop/Bad Cop-style pair named Marc Klaw and Abraham Lincoln Erlanger from an office on (Where else?) Broadway, in New York. The two of them were also named as producers of the majority of the plays that were performed in theaters owned by The Trust.

That organization's story could fill an entire book all it's own, much less a blog post, but I'll try to hit the high points here. The Theatrical Trust was run by a Good-Cop/Bad Cop-style pair named Marc Klaw and Abraham Lincoln Erlanger from an office on (Where else?) Broadway, in New York. The two of them were also named as producers of the majority of the plays that were performed in theaters owned by The Trust.

The Theatrical Trust's Good Cop/Bad Cop team, Marc Klaw(L) and Abraham Erlanger (R). These two pretty much controlled the entire American theater scene in the early 20th Century.

|

Though the Theatrical Trust...also known as The Syndicate...had only been around since 1896, by 1903 it had an iron-fisted grip on just about all of the major theaters in the U.S. They controlled which theaters got major productions and which ones got second or third rate plays, and by the same token they controlled which producer's plays were performed in major markets and which ones went to second and third rate theaters in smaller cities. Underhanded tactics were pretty much the norm, and Klaw and Erlanger were not well liked by anyone in the entertainment industry, be they actors/managers/theater owners or members of the press.

They were said to have had the 'Good Cop-Bad Cop' method of doing business down to an art form, with Klaw being the sophisticated and eloquent speaking 'Good Cop', while Erlinger was the harsh, rude, demanding 'Bad Cop'. Utilizing this method, they regularly intimidated theater owners/producers/ etc into doing their bidding. That being said, getting under the wing of The Trust all but ensured a theater's success...as long as they kept Klaw and Erlinger happy.

Keeping those two happy would play a huge part in the disaster to come...but we'll get back to 'The Trust' in a bit.

Now...lets take a look at the beautiful death-trap that the team of Davis and Powers planned to build.

Ok, obviously they didn't build it to be a death trap...they intended for it to be the be-all and end-all in both luxury and safety, and if everything had gone right, they just may have done just that...but then again, if every thing had gone right, I wouldn't be writing a blog post about the place.

First off, when the property for the Iroquois was purchased, it did not include the lot at the actual corner of Randolph and Dearborn. That lot was already occupied by the seven story Real Estate Exchange Building, the very same office building that's located at that intersection today, now named the Delaware building.

This meant that The Iroquois would have to be built around the Real Estate Exchange, giving it an 'L' shape. ( HMMMM...beginning to sound a bit like another ill-fated theater, ain't it??)

Of course, while the Iroquois, like the Brooklyn Theater, was 'L'-shaped, and while the two theaters did share a vaguely similar layout, that's where the similarities between the two stopped.

**

Front view of the Iroquois...or actually the former Iroquois, as this photo was actually taken a year or so after the fire, during the theater's short stint as Hyde and Behman's Theater. The striped canopy over the front entrance, and the bust of an Iroquois Indian that once resided above the front entrance were both removed after the post-fire renovation. Though it was no longer The Iroquois by the time the pic was taken, you can very much still see the level of grandeur that Architect Benjamin Marshall designed into the building

|

A Stereograph pic of the intersection of Randolph and Dearborn Streets, with the by then former Iroquois Theater visible obliquely dead center of the frame. The large, dark brick, multi-story building at the corner of Randolph and Dearborn is the Real Estate Exchange Building, which still stands today as The Delaware Building. The cigar store visible at the front of the building is both where the Iroquois ticket receipts and cash drawer would be taken for safe keeping and where the first telephone report of the fire was called in from. A MacDonalds occupies that same space today.

A quick word about stereographs. This is actually half of a double image, The two images were taken from almost identical angles and the side-by-side double image was placed in a stereoscope viewer which had a clip for the photo, mounted on a wooden rod six or so inches in front of an eyepiece that sort of looked like a very early version of the old Viewmaster toy. When you looked through the eye piece at the photo, it...sort of...appeared to be in 3D. Very popular at the turn of the 20th Century, valuable collectible today.

|

Artists drawing of he lobby of The Iroquois. You can definitely see how lovely the lobby was...and looking at the set up of the balcony stairways, how dangerous it would have been in a fire. The three first floor doorways visible lower mid-frame are the entrances to the parquet and orchestra levels of the auditorium, just above them is the 2nd floor promenade where the Dress Circle entrances were located. The 'Hanging' landing above that promenade separated the 2nd and 3rd floor promenades. The 3rd floor promenade, where the Gallery entrances were located, is above the hanging landing, at the very top of the frame. That hanging landing was an artistic...and very dangerous...touch, but it didn't trap as many people as you might think, because most of the Dress Circle and Gallery occupants never made it that far before becoming trapped in the exits and on the promenades.

And then there were the iron accordion gates...we'll talk about them later.

|

**

The very first differences between the two were size and decor.

Lets get this one out of the way first...the Iroquois made the Brooklyn Theater look like a hovel. While the Brooklyn Theater's decor had been ornate and attractive, the Iroquois took 'Ornate and Attractive' to the next level. The Iroquois was designed to one-up the most ornate play-houses in Europe and...most particularly...New York, with copious use of marble, exotic woods, and plush fabrics. It was breath-takingly beautiful inside and, unfortunately as it would turn out, much of that beauty came at the cost of safety.

As for the relative sizes of the two buildings, even though the Iroquois and Brooklyn Theaters were both designed to have the exact same seating capacity...1600 seats....The Iroquois was a far larger building. The Iroquois' lobby wing, where the main entrance, lobby, facilities such as checkrooms and restrooms, entrances to the Auditorium's main floor, and the stairways providing access to the balconies were all located, was six stories tall, and fronted 45 feet on Randolph Street...three stories taller and nearly twice as wide as the Brooklyn Theater''s entrance wing...while the 120 foot long auditorium wing, containing the auditorium, stage, and back stage areas, fronted 110 feet on a narrow vacant lot off of Dearborn Street, a third again larger than The Brooklyn Theater in all dimensions.

The only part of the Iroquois that wasn't considerably larger that the Brooklyn Theater was the auditorium... as in the actual audience seating area...itself. In fact, dimensions-wise they were about the same size. Both theaters also boasted two balcony levels, but this is where the Brooklyn Theater was actually a little better than the Iroquois. Because of an architectural design error, the Iroquois' second balcony...home to the theater's least expensive seating, tucked up against the theater's ceiling, and known as the Gallery,... had far more steeply pitched rows of seats than those in the Brooklyn Theater's 'Family Circle', with a twenty-five inch rise between rows...far steeper than even modern football stadiums. So steep, in fact, that brass railings were installed between rows to assist people walking to their seats, as well as to keep those already seated from tumbling head over heels if they tripped while standing back up.

**

The first floor floor plan of The Iroquois, showing the theater's 'L' shaped design. The fire exits were along the north wall, directly opposite the entrances to the auditorium...this was true on both balconies as well. The square with a cross with-in it was the elevator, the six levels of dressing rooms would have been between the elevator and the theater's back wall. The light bridge where the fire started was on the the 'Stage Right' side of the stage (Left side as you face the stage), hard by the elevator, with he buildings main electrical switchboard tucked beneath the light bridge.

The two stage doors are also visible...the Dearborn Street stage door, located hard by the dressing room wing near the building's southwest corner, and the Couch Place stage door, which was a 'Wicket Door', with a small personnel door nested within a larger scenery door, located on the other side of the stage at the building's's northwest corner. Keep the Couch Place stage door in mind...it would play a huge and tragic part in the fire.

|

**

The Iroquois' stage and backstage areas, however, with a total square footage of 5,750 square feet, were far larger, than those of the Brooklyn Theater. The Iroquois boasted six levels of dressing rooms, situated along the backstage area's south wall and served by an electric elevator, which was considered an extremely high-tech feature in 1903. There were also stage offices and dressing rooms below the stage, accessed by a stairway on the south side of the back stage area..

Of course, there were two major differences in the layouts of the Brooklyn and Iroquois theaters. The first was the way the auditorium was oriented to the lobby. The Brooklyn Theater's auditorium was actually located to the side of the lobby, with the entrances to the lower level to your left as you entered the lobby and a stairway accessing the first balcony ahead of you. As you walked in to the Brooklyn Theaters first level through one of those entrances, you were at the rear of the auditorium, with the stage directly in front of you.

The Iroquois lobby, on the other hand, was far larger. You entered the Iroquois through one of six elaborate glass and mahogany doors to find yourself in a lavishly decorated forty-five foot wide, fifty foot deep, six story high marble and mahogany lobby, called the grand stair hall...with ornate stairways on either side of you and the three entrances to the first level of seating (The Parquet and Orchestra level) directly ahead of you. If you had an Orchestra or Parquet level ticket, when you entered the auditorium through one of those three entrances to the Orchestra Level, you were at the side of the auditorium with the stage to your left, and the sides of the rows of seating directly in front of you. The entrances to both balcony levels were, of course, oriented similarly.

The second, and biggest, major difference between the two theaters was access to the balconies. The Brooklyn Theater featured separate stairways for each balcony with a separate outside entrance for the Family Circle (Topmost balcony). If you read the Brooklyn Theater post, you may remember that that very circuitous Family Circle entrance/Exit path became a death-trap.

The Iroquois architect managed to make his stairways even worse by having the exit paths from the two balconies meet in a restricted space. I'll take a more detailed look at this when I discuss the fire itself, but lets take a look at how you'd access the balconies.

If your ticket had been for a Dress Circle or Gallery seat, you'd climb one of those twin stairways, both of which climbed through a series of five 'straight through' landings, until they reached a balcony above the Parquet Level entrances. When you reached that balcony, you could either go straight, and enter the first balcony level, called the Dress Circle, through any of three ornate doors, or you could turn (Depending on which stairway you climbed) either right or left, and climb yet another set of steps that passed through a long 'hanging landing' before turning 180 degrees and climbing to a similar balcony serving the Gallery's (the topmost balcony level) two entrances. Then, owing to the top levels extremely steep pitch, if your seat was at the very rear of the balcony, you had yet another short staircase to climb before reaching your seat.

Theses balconies, promenades, stairways and landings were elaborate, beautiful, allowed everyone to see and be seen, and, owing to the fact that they created numerous pinch points, they were deadly in a fire. Keep them in mind...they become real important here in a bit.

The differences in size and grandeur and access between the two buildings, while notable, were far from the biggest differences. Will Davis and Harry Powers, as you recall, intended the Iroquois to be one of the safest, most modern, most technologically advanced theaters in the U.S, if not the world. That backstage elevator was just one of the theater's technological innovations.

First, speaking of electricity, the theater's lighting would be all electric. OK, this wasn't really that new...The very first electric, incandescent lighting system to be installed in a theater (Both stage and house lighting) was installed in London's Savoy Theater in 1881, with Boston's Bijou's Theater getting the first theatrical electric lighting system in the U.S. a year later, so electric lighting in commercial buildings had already been around for a couple of decades.

By the time ground was broken for The Iroquois on May 1st, 1903, electric lighting in large commercial buildings...the ones located in major cities at any rate...was very common, and every new theater was being built with electric lighting for both house and stage lighting, so electric lighting in the Iroquois was pretty much a given from the git-go.

Electric lighting in Rural areas was a different story, though. Electric lighting in homes... especially rural homes...still lagged behind electricity in urban commercial buildings by miles in 1903, so many people still considered electric lights to be just shy of actual wizardry. People who traveled from their kerosene lamp lit rural and small town homes to see a play in Chicago would stare in unabashed wonder at these flameless sources of illumination that required only the flip of a switch to light.

Much of the Iroquois theater's new technology was safety and exit technology related. The Brooklyn Theater Fire, along with the even deadlier Ring Theater Fire, in Vienna, Austria five years later, taught a slew of lessons RE: Theater Fire Safety, and the Iroquois' owners planned to heed all of them.

**

A cut-away schematic of the theater, looking in from the Couch Place side of the building. The ventilator above the stage was actually supposed to be a smoke/heat vent that could be opened in event of a fire to vent heat and smoke straight up and out, keeping it out of the auditorium. The vents were never completed, and were boarded over at the time of the fire, with tragic results. The ventilator and fan above the gallery, however, was completed, and running.

The area beneath the stage...the Sub-Stage...was not just open space., It contained dressing rooms, workshops and storage as well as the coal bin for the furnaces, which were in the basement, adjacent to the sub-stage. The chute for the coal bins was used to rescue several trapped dancers.

The scenery flats were hung vertically in the two fly galleries, which became fully involved very early in the fire, trapping both a group of German aerialists...one of whose number would become the fire's first fatality when she fell to her death...and aerialist Nellie Reed.

|

**

Almost every theater fire started either on-stage or back stage, sending smoke, heated gasses, and fire into the auditorium. The proscenium arch ( archway that separated stage from auditorium) was an integral part of the building structure in the Iroquois (And all modern theaters) but it was also the weak point of the theater, fire safety wise. A fire starting backstage and gaining headway could and would pump smoke and heated gasses through the proscenium arch and into the auditorium to endanger all of the theater's occupants, causing multiple deaths...especially in the balconies...long before flames swept through that arch to finish off any trapped occupants who the smoke hadn't already suffocated.

The Iroquois was designed to prevent that from happening.

The roof over the stage would be equipped with a pair of big smoke vents, cable operated from the main switchboard...a flip of a switch would drop counterweights which would slide the covers down tracks, opening the smoke vents and venting fire and smoke straight up and out, there-by preventing it from rolling out into the auditorium. My bet is that the mechanism that held the counterweights in place was either designed to release them automatically in the event of a power loss, or was supposed to be backed up by a fusible link.

To prevent flames from roaring into the auditorium through the proscenium arch, the Iroquois would have a weighted, fire proof asbestos curtain that could be dropped in the event of a fire, completely separating stage and auditorium, holding the fire backstage and on stage long enough for the theater to be safely and calmly evacuated. The curtain would be manually dropped, though, rather than automatic, but there was a sound reason for this...a manually dropped curtain wouldn't be disabled if the fire killed power to the building.

A sprinkler system as well as standpipes and fire hose were included in the plans. The former should keep a fire from ever getting much beyond the incipient stage, with the latter making quick work of any fire that the sprinklers didn't snuff. At least that was the way it was supposed to work.

The Iroquois was...theoretically, at any rate...also well equipped with exits as well as exterior fire escapes. There were nearly thirty exits, nine of which were dedicated fire exits on the north side of the auditorium, with the fire exits on the first level emptying directly onto Couch Place, which ran between Dearborn and State Streets, paralleling the theater's north side, while the second and third level fire exits emptied onto a pair of exterior fire escapes that also emptied into Couch Place. In theory, a capacity crowd in the auditorium could be emptied in around 4-5 minutes. Note here that I said 'In Theory'.

Basically, no fire on stage at the Iroquois should ever get past the incipient stage. If a fire, somehow, did manage to get rolling on stage, the fire-curtain should contain it, the smoke vents should pull the smoke, heat, and fire straight up and out, helping to keep it out of the auditorium, the sprinkler system should knock it down before either fire curtain or smoke vents became necessary in the first place, and the hose lines should be all but redundant. Our theoretical fire shouldn't be more than an inconvenience to the audience, who should be exiting calmly and quickly through the nearly thirty exits available to them as the fire department rolled up.

That's also what should have happened when the actual fire started, while the story about that same fire in the New Years Eve edition of the Chicago Tribune should have been a short filler article about a minor fire causing the evacuation of the city's newest theater during a matinee performance of Mr Bluebeard. But that's not the way it happened...not even close.

To tell the story of the fire, we first have to continue with the story of the theater itself.

Will Davis and Harry Powers handed off design of the building to a twenty-nine year old architect named Benjamin H. Marshall, who would ultimately become one of Chicago's most renowned architects, then contracted construction of the theater out to the George A. Fuller Construction Company...one of that era's premiere national construction firms. I'm going to give them the benefit if the doubt, at least in the beginning, when that ceremonial first shovel full of dirt was turned, because I truly think they started out with the full intent of building the most luxurious, most modern, and most importantly, safest theater the U.S. had ever seen.

Unfortrunately, shenanigans went hand in hand with the construction of the Iroquois almost from that ceremonial first shovel of dirt on Ground-Breaking Day.

Then as now, the Christmas Holiday season was when a lion's share of the entertainment industry's profits were realized so, when construction started on 5-1-1903, the tag-team of Klaw and Erlanger made it clear to Will Davis and Harry Powers that they wanted the Iroquois to open it's doors well before Christmas, 1903. In fact, they wanted it open in late October, in time for the opening of the 1903 Theater season.

Of course, with all the dictatorial control that The Theatrical Trust may have held over the industry, and all of the original good intentions that Will Davis and Harry Powers may have had when construction started on the Iroquois, there were a couple of things that none of them could control. Like Labor issues. And the weather.

The inevitable delays due to weather and such things as materials not being delivered on time, pushed the opening date back first a week or so, then a month, then six weeks until, finally, a firm opening date of November 23rd was announced to a Windy City public who had been reading about this amazing new theater, watching progress of construction, and anticipating it's opening for months.

Then that date was threatened, first by the year's first major snow, which hit on November 5th, extremely early even by Chicago standards. This storm was followed up by a couple of days of freezing rain, a combination that would have delayed construction further even without causing rail line delays that kept Fuller employees from making it to the site.

As if that wasn't bad enough, the project was also hit with a One-Two-Three punch of labor problems.

Just as the weather began to moderate a bit, only eleven days before the theater's grand opening, the New York Bricklayers Union...1000 men strong...struck every Fuller Construction contract in the Big Apple. .I'm not a hundred percent sure how a labor problem in New York would affect a construction site in Chicago, and a full explanation of the labor politics involved is far beyond the scope of this blog, but basically, with the bricklayers not working in New York, no one else could...or would... work either, and this led to across the board work stoppages. These stoppages included sites in The Windy City, once again slowing the final stages of construction at the Iroquois to a crawl.

They got that one sorted out, and then, even as the bricklayers went back to work, another, far more serious strike took place only a week or so before the theater was supposed to open, when the iron and steel workers union struck Fuller Construction. As Fuller tried to sort out these labor problems, the third, and likely most damaging, punch was thrown.

On November 14th...three days after the theaters new, firm opening date was announced...3000 streetcar motormen went on strike in a violent work stoppage that had the multiple effects of delaying workers trying to get to their jobs (Including the Iroquois site) and keeping the public from getting to places of business. The strike's violence also made husbands hesitant to allow their wives and children (Who made up a huge percentage of Holiday theater-goers) to venture down-town. The strike wouldn't be settled until November 25th...two days after the Iroquois' grand opening...and I can just about bet that the strike affected attendance those first two days. And trust me, Klaw and Erlanger did not need anything to either delay the Iroquois' opening or cut down on attendance.

As if the weather and labor problems weren't giving the Theatrical Trust enough headaches, the Trust was having other problems of its own. That iron grip they had on the Entertainment Industry had apparently been smeared with a little bit of grease because it was beginning to slip a little, and in fact, had been slipping for the better part of a year..

Several well known entertainers and a few successful theater owners had split off from the Trust to start their own syndicate and produce their own plays and thanks to this, neither of 1902/03's two biggest hits...the magically legendary Babes in Toyland in 1903, and a little play called The Wizard Of Oz the year before...were Theatrical Trust (AKA Klaw and Erlanger ) Productions.

Klaw and Erlanger were getting just a bit desperate to turn things around, but they had both a plan and a play to turn it around with.

While the Theatrical Trust couldn't claim either of the last two years' really big hits, they had had been finding success with family oriented musicals...all imported from London's Drury Lane Theater Company. They chose one of them to kick off the Iroquois reign as Chicago's Premiere Theater. The play they chose was a (for the time) special effects packed musical and dance fantasy called Mr Bluebeard that had opened at New York's Knickerbocker Theater the previous season.

They had really gambled on Mr Bluebeard being a success, by the way, because it was not an inexpensive production. To bring the production to life, a company comprising over 350 people utilized hundreds of set pieces, lights, special effects, and costumes (Most of which had to be altered to properly fit American actresses), all of which had been shipped across the Atlantic at Klaw and Erlanger's expense. Then those 350+ people had to be paid. Total outlay, before the first prop was carried through the Knickerbocker's scenery door had been around $150,000. That's just shy of four million 2017 dollars.

But their gamble had paid off. Mr Bluebeard had enjoyed a successful run, making a tidy profit, and the Trust decided to extend their rights to the production for another season (Bet that wasn't inexpensive, either) so they could open their newest and finest theater with it.

They even already had a home-town favorite...A Chicago native of amazing comedic talents named Eddie Foy...starring in the play, and had courted him for months before signing him at the then unheard of salary of $800 a week (Just over $21,000 in today's money).

SO the Trust had the tools to, despite several theater owners jumping ship, make the 1903 Chicago theater season a major success, and maybe even make their own home town's already iconic theater scene pause for just an instant and take notice.

But first they had to get the Iroquois open for business, and, frustrated to no end by all the problems and delays, they told Fuller Construction's honcho's to get the building open on November 23rd no mater what it took and, most importantly and ultimately tragically, no matter what wasn't finished.

'What about Inspections and being Certified for Occupancy, and such?' Fuller's brass may have asked. Klaw and Erlanger's reply? It was something to the effect of 'If free tickets had to be offered and palms had to be greased, so be it.'

Let the shenanigans begin.

Of course, said shenanigans had actually already started, probably before the first construction delay reared it's head, in the form of cutting corners to save money.

One item...That reinforced asbestos fire curtain...is a perfect example. And, OK., before anyone else brings it up, yep, we all know that asbestos has been proven to be dangerous to life and lung, and that inhaled asbestos fibers cause one of the most horrible modern diseases (Asbestosis) to ever be discovered, but in 1903 none of this was known, and asbestos was considered a miracle material that rendered anything it was even near fire-proof, at least according to those who manufactured and sold items made from it.

The curtain, originally, was to be made of asbestos fiber and reinforced with a brass wire frame, rendering it semi-rigid and fire resistant. Properly constructed, this curtain would have weighed somewhere between 3000 and 4,000 pounds, and would have been manually raised and lowered using a geared winch/cable/counterweight system. The base of the curtain was fixed to a rigid metal rod fitted with rollers on each end that would be slotted into a vertical track on either side of the stage. This way, when lowered, the curtain would form a semi-rigid fire-resistant barrier between a back-stage fire and the audience that, along with the stage roof vents, would hold the fire long enough to give them time to calmly exit the building.

I don't know how much this curtain would have cost, but I have a feeling that they weren't cheap. So Fuller, with full knowledge of Will Davis and Harry Powers, instead ordered a curtain that was made chiefly of wood pulp, with some asbestos fiber...enough to meet building codes...woven through it. There was no wire mesh frame to provide rigidity, though there was a metal rod slotted into a track on either side of the stage, but the tracks were wooden rather than metal.

This Faux-asbestos curtain may have met the then existing building codes, and it certainly saved money...to the tune of about $56 ($1550 in 2017), but it was just about as fireproof as a paper towel. Which meant that that $56 was saved while robbing the theater's patrons of a a major safety feature while giving them the impression that it was, indeed, still there.

And it got worse...The sprinkler system that had been in the original plans (And that was actually required by Chicago building codes) was somehow deleted from the actual construction process. The standpipes, with multiple hose connections, were installed...but without hose or fittings. They would have been useless anyway, because the standpipes hadn't been connected to the city water system, nor did it have a roof mounted water tank large enough to both supply water to the system and pressurize it. While there was a water tank on the theater's roof, it was a small one whose purpose was to supply water pressure to flush toilets.

There was also no fire department standpipe connection to allow an engine to pump into the system, supplying it. So the standpipe was nothing but a useless, empty pipe. Even worse, these 'oversights' were somehow 'missed' by building inspectors. Spoiler alert...That's going to be a recurring theme here.

Remember that high-tech roof venting system above the stage? Those construction delays... especially, most likely, the problems with the iron workers union...delayed completion of the automatic roof vents above the stage and back stage areas (Probably delaying installation of the tracks that the missing counterweights, which opened the vents, slid up and down in). Make that 'prevented completion', as in, when the theater opened on November 23rd not only was the roof venting system not finished, it apparently wasn't going to be finished anytime in the immediate future. In fact, boards were actually nailed over the roof vents themselves, apparently to prevent cold air from entering through them.

A large ventilator above the auditorium, which was part of the normal heating and ventilation system and was designed to draw air up and out of the auditorium, was completed and operational. These two facts alone would be a huge factor in the fire, and the deaths resulting from it.

Then there were the fire escapes. While some sources say they weren't finished, leaving only blind platforms hanging over Couch Place, photographs (Including the best known photo of the fire) say otherwise...the fire escapes were there. There were nine exits leading to these exterior fire escapes alone. But there were still a bunch of problems with these exits.

First, the way the exits were set up was a major problem in and of itself. The fire exits utilized 'stacked' doors, with double glass doors (Equipped with difficult to operate bascule locks) inside and windowless iron doors (Equally difficult to open.) outside. So even getting out of the fire exits onto the fire escapes posed a major problem.

Then, once the theater patrons got out of the fire exits onto the fire escape landings, things got even worse. They could only assume that if a exit was provided, that a way to safely reach the ground would also be provided, and this should have been a given. This, as we'll see, would turn out to be a lethal assumption.

The stairs were there, but were were poorly designed. We'll go into just what these design flaws are later, as we examine the fire as it's in progress, but lets just say that the stairs would be completely obstructed before the evacuation really got under way, leading to a choice between burning to death or a forty foot drop to just about certain death on the cobblestones of Couch Place.

You'd think it couldn't get any worse but it could and did. As preparations to open the theater began, and newly minted ushers and cashiers and elevator operators and all the other people needed to run a major stage theater were trained, one thing was missing in that training...what to do in case of a fire (Or any other emergency for that matter)

So as commemorative programs for the Grand Opening were ordered and printed, and rehearsals for the performance were held and last minute inspections were allegedly supposedly carried out...the inoperative roof venting system was nailed closed and covered, the fire escapes were death traps waiting to happen, and no one who worked in the place had a clue as to what to do if it caught on fire.

And these weren't, by far, the only hazards in the new, supposedly uber-safe theater. They were just the most obvious. OK, you ask, why didn't the fire inspections, or final inspections by the building department or somebody find these problems and forbid the theater from opening until they were corrected?

Anyone by any chance remember me mentioning shenanigans? Eight or so weeks before the theater opened, city Building Commissioner George Williams submitted a study on Theater Fire Safety, with the intention being to amend the building codes, bringing the hammer down on the unsafe practices that were still all too common in theater construction and management. Problem was, the proposal, and new ordinances, were shelved pending further study.

Me thinks the timing on shelving this proposal was not coincidental.

Of course, even with action on this study tabled indefinitely, the theater shouldn't have opened with a single...much less multiple...major fire hazard(s) still existing, because the Iroquois' owners hired a retired Chicago firefighter named Bill Sallers, to act as the 'House Fireman'. His primary duty was attending each performance to ensure that the theater's exits and exit paths were clear and unobstructed, inspect the in-house fire equipment to ensure it was in good order and ready for use, and ensure that the theater wasn't over-crowded as it filled before each performance. Also, if a fire got going anyway despite all of the precautions, he was there to make the initial attack on it, to, hopefully, hold it until CFD rolled in.

His secondary duty (And to be technical, primary duty before the theater opened ) was to clue the owners and builders in on fire hazards so they could be corrected before they actually became safety issues.

Awesome idea in theory...but there were lots of problems in practice.

Lets take a look at 'Checking exit paths and fighting incipient fires' first.

There were no exit signs, (The architect felt that they'd be 'distracting') and some of the exits were hidden behind draperies (Wouldn't want an ugly ol' fire exit marring the theater's elegant decor, now, would we?). Several of the exits utilized difficult to operate Bascule locks, which were common in Europe, but rare in the U.S., meaning very few people on this side of The Pond could operate them in broad daylight when they weren't panicking...much less in choking, smoke-filled darkness when they were.(Those big, ornate, brass Bascule locks sure were pretty, though!!)

**

The infamous Bascule Lock. I wish I could have found the legend that identified the numbered parts, but it wasn't included. Best I can figure out, you had to pull the latch, marked '1', towards you, which rotated the locking pins at the top and bottom of the door away from the lock plates, allowing you to swing the door open. Not at all intuitive when you're used to twisting a knob and either pulling or pushing the door.

Now! Imagine encountering this beast in a building full of smoke when you're terrified, can't see, can't hardly breath, and have several hundred panicking people behind you trying to push through the door.

**

|

On top of that, during performances the theater management locked accordion gates across the landings on the stairways between the upper gallery and the Dress circle, to keep Gallery patrons from sneaking down to better seats...Sallers was not provided with a key.

Now! Lets take a look at the 'Controlling Incipient Fires part of the deal.

He couldn't control a small fire if it got started for the simple reason they left him virtually no equipment to fight a fire with. Or, for that matter, even to report one with.

Of course the sprinkler syste...oh, wait, there was no sprinkler system. It had, as noted above, disappeared from the theater's final plans. The standpipes were still there...but they were useless. The only firefighting equipment that was retained were six...count 'em...six three foot long tin tubes, each about an inch and a half or so in diameter, each filled with about three pounds of a dry chemical known as Kilfyre. It was intended to be thrown (Forcibly, as the label indicates) onto the fire, and it was actually designed to be used on minor household fires, chimney fires in particular.

**

The infamous Kilfyre extinguishers. Six of these three foot long, inch and a half diameter tubes, filled with a dry chemical fire extinguishing agent, were all of the fire fighting equipment that The Iroquois could muster. It even had a model name...'The Monarch'. The discharge end was apparently on the bottom of the tube...the directions stated to 'Yank Down (Thus Removing Cover) Hurl Contents Forcibly with sweeping motion into the base of the flames. It also advised the user...in bold type...to

ALWAYS THROW FORCIBLY NEVER SPRINKLE

It could also be used on flue fires (Chimney fires) by pouring some of the contents into a container and tossing it into the fireplace or stovepipe opening below the fire.

The thing may have been OK on a small fire burning on the floor or the classic 'Pan On The Stove' fire, and may even have been effective on chimney fires, but it was...as Bill Sallers was to find out...absolutely useless for stopping a fast moving fire running up a vertical surface, such as curtains, located above the user.

|

**

Those six tubes of Kilfyre, folks, were all Bill Sallers had available to him in the event of a fire at the Iroquois..

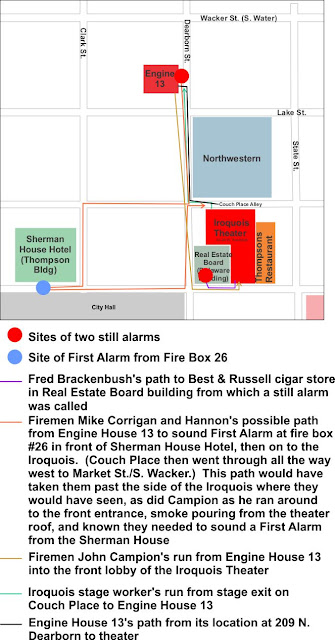

And reporting a fire? Wasn't happening, not quickly anyway. There was no fire alarm box in or even near the building...closest one was at the corner of Clarke and Randolph, in front of the famous Sherman House Hotel (The very hotel where most of the first-billed cast of Mr Bluebeard were staying), nearly two blocks from the theater. First Due Engine 13's firehouse was actually closer to the theater than the nearest box.

'How 'bout a Telephone?' You ask. Good luck with that...Even though telephones had become a part of urban life by late 1903, especially in commercial and government buildings, there wasn't a single phone back stage in the Iroquois, and only a couple, apparently, in the entire building.

The situation should never have gotten anywhere near that bad, though, because, as noted above, Sallers was actually hired well before the theater opened, and was supposed to point out fire hazards to the owners and management of the theater so they could be corrected before they became an issue.

He should have pointed these problems out to Mssrs Davis and Powers, and if that didn't yield any results, made a bee-line to the fire department and reported the issues to them.

Didn't work that way. Or even close to that way.

Oh, Sallers was, indeed aware of all of these problems and hazards and had pointed them out to Mssrs Davis and Powers, who equally obviously, simply ignored him...after advising him that his job depended on him also ignoring the problem. Remember, The Trust wanted the theater opened before the Christmas Holiday Rush at all costs.

Also, Sallers had previously had been fired from a similar job at McVickor's Theater for over-zealously attempting to enforce fire regulations. And now he was being told he was in danger of losing this job as well. SO , with his job on the line, and knowing the threat to fire him was not an idle one, Sallers made absolutely no mention of the theater's many issues to the Fire Department...even though CFD Engine 13 was quartered less than a block away, on Dearborn Street, literally with-in sight of the new theater.

Then again, as it turned out, even if he had mentioned it, it may not have made any difference.

Say What???' you ask. 'Read on', I say.

Sallers was actually called out on the fact that he never notified the Fire Department of the theater's many fire safety issues, and it was Engine 13's Captain that called him out on it.

Back in 1903, firefighters pretty much lived at the stations. There was one 'platoon' rather than the three or four shift system departments use today, which meant that the twelve or so firefighters watched this huge new theater that they were not only first due on, but less than a minute away from, take shape and form daily for six months. It would have been nice to have taken a tour of the place as it neared completion, to see just what they would be facing if caught a run there, but the technology of the era...or actually, the lack of technology...got in their way. The lack of radio communications back then prevented the guys from going 'In the district' to tour the theater as it was being built because they'd have no way to receive alarms.

This didn't, however, prevent Engine 13's captain, Patrick 'Paddy' Jennings, from touring the theater, possibly on one of his two or so times monthly days off, with Bill Sallers in tow. He, after all, would be in command of the first in engine if they caught a working fire at the theater, so he felt like he should familiarize himself with the theater's layout, features, and hazards so he could tell his guys what they would be up against should they have a fire there. Not as good as the entire company roaming around the place and seeing first hand what kind of problems they could potentially face, but better than nothing.

He'd also heard that, due to the theater's ultra-modern, high-tech fire safety technology, any fire call at the Iroquois would likely be more of an inconvenience than anything else and he wanted to see just how true this was. He'd quickly find out that this was far from accurate.

Paddy Jennings about had a major conniption as he looked at the disaster waiting to happen, and (Probably very colorfully) demanded to know why Sallers hadn't swung by #13 and let him know about the theater's many and varied fire safety problems.

Simple, Sallers replied...he didn't want to get fired. As noted above, he literally feared for his job if he brought up the fact that the theater was a very luxurious fire trap...a situation he was, theoretically at any rate, hired to prevent.

Captain Jennings replied , bluntly, that if a fire got going during a performance and Sallers' complicity in the lack of fire protection became known, that the families of the inevitable fatalities would find and lynch him. Jennings was pissed.

He didn't have an actual Fire Prevention Bureau to contact...Chicago wouldn't have one until 1911...but he did have a Battalion Chief, quartered in the same house as Engine 13, so as soon as he returned to quarters, Jennings made his way to the Battalion Chief Jack Hannon's third floor office and laid his findings out, telling the Chief that 'If a fire gets going on stage or back stage, it'll be frightful' (I have a feeling the actual conversation may have been a scosh more colorful.)

The thing is, Chief Hannon simply answered 'What can we do about it, Paddy? They've got Bill Sallers there, they know all about the problems and don't seem too worried about it'.

The unspoken conclusion of the discussion was 'Just Drop It...something my mind definitely struggles to get around even though it was a far different time and era.

Believe it or not...it gets even better. While there wasn't a Fire Prevention Bureau, there was a building department, and they were responsible for inspecting public buildings to ensure that they met building codes and that they were safe for occupancy. New construction had to be certified safe for occupancy before the first paying customer was allowed inside.

Responsibility for inspecting the Iroquois as it was being built fell to Deputy Building Inspector Ed Loughlin, who passed the Iroquois with flying colors without even filing a written report...he simply told his boss that the building was completed, safe, and OK for occupancy.

So, as the theater's grand opening loomed, the building was actually far from finished...but no one apparently cared. Worse, it was actually certified for occupancy despite all of the unfinished and/or faulty/poorly designed/non-existent fire safety equipment and fire escapes.

The public didn't have a clue. Half page newspaper ads espoused the theater's luxury, modern features, and, ironically, safety, and plans were made by people from a radius of a couple of hundred miles of Chicago to bring their kids into the big city over the Holidays to see Mr Bluebeard, which would've been a once-in-a-childhood treat for rural kids back in the first decade of the last century.

Interestingly, a seemingly minor incident provided both a bit of foreshadowing of the coming disaster as well as final chance to avoid it. The sets for Mr Bluebeard included dozens upon dozens of scenery flats, many of them delicate bordering on lacy and all of them heavily painted with oil paints to the point that they were, basically, solidified gasoline. All it would take would be a tiny spark...

Supposedly Will Davis stopped by the theater one afternoon shortly before it opened to see the sets being off loaded from a couple of big freight wagons and carried in through the scenery doors off of Couch Place. He took one look at the heavily painted, highly flammable scenery flats, went goggle eyed, and said 'That has got to be the most goddamn flammable mess of scenery I've ever seen in my life! No way it's going in my theater!'

He supposedly actually told the teamsters and stagehands who were carrying it inside to carry all of it back outside...but then reconsidered. Erlinger had an absolutely volatile temper, Klaw and Erlinger owned a percentage of the theater and the production, so pissing them off could mean he was out of a job, and delaying the opening of the Iroquois by so much as an extra day was a perfect way to piss them off.

So he told them 'Ok, take it in...we'll try to get along with the damn stuff!'

Among the items that were taken in were a big pedestal-mounted carbon arc spotlight, which used an electric current arcing between a pair of carbon rods to create a bright, directable beam of bluish-white light. While they created plenty of light, they also drew an immense amount of current. And they had a bad habit of shorting when they pulled too much current, creating a spark when they did so.

All of the elements of the disaster were in place.

******************************************************************************

Satellite view of the intersection of Randolph and Dearborn today. The building at the intersection's northeast corner is the Delaware building, formerly the Real Estate Exchange Building, and is the only building still standing that was around in 1903. The 'L' shaped Iroquois was built surrounding it on two sides. The eastern third or so of The Real Estate Exchange was partially razed in 1924, along with the former Iroquois Theater and much of the rest of that block, to make way for the United Masonic Temple Building, which also contained The Oriental Theater. The Oriental, of course, is still there, and still thriving.

I've also indicated the approximate footprint of the Iroquois as well as the location of the Iroquois' exterior doors, and the location of Thompson's Restaurant, next door to the theater, which became a 'Field Hospital' of sorts during the fire.

|

Christmas has always been a kids holiday...Oh sure, adults exchange gifts as well, but just about everything about the commercial side of Christmas was created with kids in mind, from stockings and Santa to holiday entertainment, and Mr Bluebeard was not only no exception to the rule...in fact, it was a kid's dream come true. On steroids.

Mr Bluebeard was loosely based on the fable about a wealthy, violent monster who had married and killed 7 wives, and his eighth wife's attempts to avoid the same fate after she went into a forbidden room in Bluebeard's castle and discovered the bodies of wives 1-7. OK, I can see the horrified, questioning looks as everyone asks, mouth agape, 'That was a kids play???'. As originally written, it wasn't...to make it kid-friendly, the story was given a happy ending (All seven deceased wives came back to life), put to music, and Americanized a bit.

While it wasn't a Christmas-themed play, it was still very much a kid's play, with lots for kids to love... Exotic and colorful (And, as noted, highly flammable) backdrops, amazing special effects (Most made possible by the same thing that would cause the fire...electric lighting), spectacular musical numbers performed by huge, gaudily dressed dance troupes, whimsically costumed characters, a baby elephant (Actually a couple of actors in an elephant costume), Eddie Foy in hilarious drag (He was a brilliant comedian, and reviews of the play said he was seriously underused...he'd also be considered the hero of the day.) and an aerial ballet featuring a dancer who actually 'flew' out over the audience, on a wire.

Of course the dangers weren't apparent, and had remained dormant for the nearly a year that Mr Bluebeard had played in the U.S, during both it's run at Broadway's Knickerbocker Theater, and a mini-tour of the Midwest it embarked on to keep the profits rolling in while the Iroquois was under construction. Klaw and Erlanger knew that the play's appeal to children made it perfect for the premier run at what promised to be the nations most luxurious, safest, most technologically advanced stage theater, so they went all out, even as they sweated the construction delays.

The Iroquois had been advertised heavily and constantly...or as constantly as a world without electronic communication would allow...with all of the major Chicago papers running articles about both the theater and the play, as well as half and full page ads, for weeks before the opening, which was timed well despite it's being a month into the new theater season. November 23rd was the Monday of Thanksgiving Week, and Thanksgiving, then as now, was pretty much the kick-off of the Holiday Season, though it was dozens of times more low-key in 1903 than it is today. Then as now as well, theaters made a big hunk of their annual profits over that five or so week period. And, As I've noted, Mr Bluebeard was the perfect play to make said profits with.

A capacity crowd turned out for Mr Bluebeard's premiere Chicago performance despite the still on-going motorman's strike, and though the critics were a bit disappointed in the play's weak plot, they raved about the special effects, colorful costumes and sets, dance numbers, and in particular, Eddie Foy's performance, and were very impressed with the Iroquois.

While the critics weren't quite sure what to make of the play's weak plot, the target demographic loved it...kids, generally, could care less about the plot's sophistication, or lack there of, as long as it's fun to watch.

**

Yep...souvenir programs were very much a thing even 115 years ago. Here we have the front cover of the inevitable souvenir program, available to those attending the grand opening and premier performance at the Iroquois on November 23, 1903. The picture on the left is an an enlargement of the illustration on the cover.

|

Mr Bluebeard starred Home Town Boy Eddie Foy, shown here in a head shot from the era, and in costume (And drag) as Anne, the ugly sister of Fatima. He would end up being considered one of the heroes of the fire.

|

**

The play enjoyed pretty good attendance right on through the first couple of weeks of December, though not quite as high as owners and producers had hoped, but that would soon be a non-problem. Remember, Mr Bluebeard was basically a kids play. And one thing that hasn't changed much over the past century and change is the amount of time kids have off for Christmas, at least here in the U.S.

Traditionally, kids in just about every school system in the U.S have gotten two weeks...Christmas Week and the week between Christmas and New Years...off for Christmas. This has been happening for at least the last century and a quarter or so, and it's likely what the kids in Chicago had as a Christmas Break in 1903....very probably from Monday the 20th to Monday, Jan 4th, 1904. And that's exactly what Klaw and Erlanger were counting on.

Twice a week (Saturday and Wednesday) Matinee performances were added during those two weeks, bringing about exactly what Klaw, Erlanger, Will Davis, and Harry Powers had hoped for. With the kids out of school, parents decided to give them a special treat, in the form of shopping in the many high-end stores 'In The Loop', lunch at a good restaurant (Many of them probably ate at Thompson's, a popular restaurant right next door to the Iroquois) and finally, attending the afternoon matinee performance of Mr Bluebeard.

Because the men of the house had to work, it was usually the moms, or sometimes aunts or nannies, who brought the kids to the afternoon matinees, and they showed up in droves, as did groups of high school kids, especially the girls. During an interview after the fire, Eddie Foy would note that the play had enjoyed big crowds the entire week after Christmas, crowds that seemed to get larger with each successive night.

And then came December 30th.

The day before New Years Eve, 1903 dawned clear and frigid in Chicago, with a little bit of snow on the ground and temps hovering right around zero. This was shaping up to be a cold winter in Chicago (And would, in fact, end up being the coldest on record) but the frigid temps didn't do anything to slow the influx of moms, kids, and families who converged on Chicago's Loop from thirteen states and eighty-seven cities.

People had planned day-trips around this performance. Remember, back in 1903 going into Chicago wasn't just a simple affair of getting into the trusty Family SUV and jumping on I-55 or I-94. For the vast majority of families it entailed making a trip into town by train, which meant round-trip train tickets also had to be purchased, then everyone had to be up early, bathed, dressed, and at the train station, ready to go when the train rolled in to the station. It's a good bet that lunches may have been made and packed, unless a lunch in a restaurant was planned.

It was a day loaded with excitement for the kids, who were already in the middle of that sensory-overloaded week-long sugar-high giddiness that's the awesomeness of Christmas as a child. The train ride, day in the big city, and seeing Mr Bluebeard were just icing on the cake (And very likely part of many of the kids' 'Santa Claus' )

Of course, they also had to get tickets to the show. Back then, of course, there was no buying tickets online ...you had to actually go to the theater's box office and purchase them. They could still be purchased in advance at the box office, but you pretty much had to live in Chicago to do so. Those coming from out of town had to buy tickets at the door.

**

A ticket to Mr Blue Beard from Dec, 30, 1903...but this was one of the tickets that would never be sold. This one...in the Orchestra section, on the auditorium's first level...was for the evening performance which, of course, was never performed.

|

One of the ticket stubs from the fatal performance, held by an occupant of orchestra section, on the theater's first level of seating. Just about everyone on the auditorium's first level made it out safely, so this stub was very likely held on to by a survivor..

|

**

The Iroquois' box office was located in a vestibule between the theater's inner and outer exit doors (Two groups of six identical glass and mahogany doors). With that afternoon's matinee performance starting at around 2PM, a crowd was already queuing up at the box office well before 1PM, filling the vestibule up to overflowing, then probably forming a line that extended down Randolph Street. With school out for the holidays, the line was packed with moms and kids as well as groups of teens.

The tickets kept selling, until all 1600 seats had been filled, and this made Davis and Powers more than happy because, as I noted above, crowds, while good, had been disappointingly short of being a full house. So they told the ticket-sellers to keep on selling standing room tickets until they managed to stuff another anywhere from...depending on the source...two to five hundred more people inside the theater. According to many witnesses there were people standing four deep along the back walls of all three levels as well as standing or sitting on camp chairs and stools in the aisles. (Though actual records seem to refute this....more about that in 'Notes')

They sold so many tickets, in fact, that the show's star...Eddie Foy...even got shut out. Being on the road constantly, he didn't get anywhere near enough Family Time, so his wife and kids were in town over New Years to visit him, and he tried his best to get passes for them to attend the Wednesday afternoon matinee...but he was too late. By the time he tried to get passes, all of the seating had been sold out, and they were well into 'Standing Room Only' mode. After a quick parental discussion a very fortunate decision was made...his wife would take the kids shopping (Or maybe take herself shopping, with the kids in tow) instead. There would, after all, be other chances to see Eddie perform.

The oldest Foy child, six year old Brian, begged his dad to take him anyway, so Eddie relented and brought him along, trying one more time to get him a seat...or possibly even just a folding chair...near the front,

No room, though a folding chair was likely what he sat on when his dad, instead, took a look at the wings of the stage and realized he could stow Brian on stage...or just off stage. There was an alcove of sorts, just off of 'Stage Right (The left side of the stage to the audience) hard by the main switch board and beneath one of the 'Fly bridges' that both supported lighting equipment and provided access to the overhead scenery storage known as the fly gallery. That would be a perfect place for Brian to watch the show...And lets be honest here, a six year old boy would much rather be back stage, where he could watch all of the action. And next to the switchboard, where he'd get to 'supervise' the high-tech stuff? Even better in the mind of any six year old boy!

So Eddie grabbed the afore-mentioned folding chair and placed it in the alcove, let stage managers and the electricians running the switchboard know where he was putting Brian so they could keep an eye on him, then headed for his dressing room to begin the likely long, drawn-out process of becoming Anne, the the ugliest of the seven ugly sisters of Fatima, who was the lust-object of the titular Mr Bluebeard. (It's a good bet that Brian tagged along to watch this process, too.)

And, as a now fully costumed Eddie brought Brian back to his place of honor next to the switchboard, he glanced through a small opening in the curtains to see a huge crowd awaiting the performance. Every seat in the house filled, with people standing along the back walls.Among them, he'd note later, were 'More mothers with kids than I've ever seen at any performance...

Meanwhile, as Eddie Foy installed his son next to the switchboard and glanced out at the crowd, just above them, on the Fly-bridge, electrician William McMullen was probably in the process of testing a big carbon arc spotlight, maybe even letting their new 'assistant' throw the big knife switch that sent power to it.

The entire theater was humming with the energetic controlled chaos that's a major stage production as the clock ticks down the last half hour or so to show-time, and the audience could feel it. Young girls tittered and giggled (And checked out the actors) and young guys preened (And checked out the young girls...some things haven't changed in 115 years.) and kids all but shivered in anticipation as moms and dads pointed out details of tech and beauty.

And finally, the curtain opened and the houselights dimmed. All of us have been in a movie theater when the lights finally dimmed all the way and the feature started, and you, as it's been said, can almost hear the silence. It was the same as the houselights dimmed at the Iroquois that long-ago afternoon, but even more-so, spiced with youthful and childish anticipation...

The show had started. Over a third of the audience had just begun their last hour or so of life.

The first act went off without a hitch, much to the delight of the audience, especially the kids. The song and dance numbers were spectacular, the special effects amazing, and everyone loved the young, lovely, petite and very talented teen dancers of the Pony Ballet as they cavorted and swirled across the stage. The antics of Eddie Foy were hilarious, what they had gotten to see of them so far. He'd hit his stride in Act 2, when he would, among other hilarity, dance with an elephant (OK, again, it was a couple of actors in an elephant costume...)

It was probably about quarter to three or there-abouts when the curtain dropped on Act 1, kicking off a general rumbling and jostling of activity among the audience as moms took kids to the rest room, and the men-folk gathered in the smoking room to enjoy cigars, as others headed for the 'Crush Room', as the huge foyer was also called, to mingle during intermission.

If you think there was a lot of activity in the audience, back stage things went into overdrive. Flymen heaved on ropes to raise the old backdrops and lower new ones into place while Prop-men quickly and efficiently organized various set-pieces so they'd be available in the right order.

One of the biggest jobs was handled by riggers as they set up the wire for lovely young dancer Nellie Reed's aerial ballet...she'd actually fly out over the audience dropping flowers...and as some of the riggers strung her flying wire, another assisted Nellie in donning the leather and steel 'Greek Corset' that she wore beneath her costume. This beast looked like the top half of a leather suit of armor (And was probably just as comfortable) and came complete with a hook on the back that allowed the wearer to be attached to the flying wire.

Nellie Reed, who would be one of only two fatalities among the Mr Bluebeard cast when, while still attached to the wire used for her aerial act, she became trapped above the fire.

|

Early in the second act, a double octet...a group of sixteen dancers...would dance to the hit song 'In The Pale Moonlight', the exact breed of performance that the big carbon-arc spotlights were designed for.. Up on the flybridge, Bill McMullen slid a blue-tinted sheet of isenglass into a pair of guide slots on the front of the spotlight he was manning that evening. This would give the lighting for the octet a blue glow, simulating a moonlight effect. Of course, In The Pale Moonlight' wouldn't be performed for another fifteen or twenty minutes or so, but he also wouldn't need that carbon-arc light until then, so now he was ready to go.

The house lights flashed several times in the traditional signal that intermission was over and Act 2 was about to begin.

*****

The second act kicked off just as smoothly as the first, keeping the hundreds of kids in the audience wide-eyed with wonder. Eddie Foy once again had the audience in stitches as he cavorted with the dancing elephant, then, as his first scene in Act II ended, he checked on Brian, who by by then was probably happily in Coolness Overload. Once he made sure Brian was OK, Eddie headed for his dressing room to touch up his make-up and get ready for his second performance of the act, a fantasy sequence as the Old Woman Who Lived In A Shoe.

Nellie Reed's aerial act was also flawless and awe-inspiring, made even more so by the use of lighting. Some of these lights were housed in twenty inch tall, five inch wide retractable reflectors, called 'Front Lights', mounted on either side of the proscenium arch. They were hinged vertically, and when not needed could be swung into wells in the arch's wall, so they'd be out of the way of the curtain, and most importantly, the fire curtain. Nellie Reed's aerial performance was the only time during Act 2 that the front lights were needed, and once she finished showering the audience with flowers, stage hands should have swung the lights on both sides of the stage back into their wells. And they did just that, swinging the lights on the stage-right side of the stage closed. The one on the stage-left side, however, didn't catch completely, and bounced back open a couple of inches. In the tumult of activity that's a major stage production, no one noticed.

The Octet's sixteen performers were waiting in the wings as Eddie Foy headed for his dressing room to make his quick costume change, and it's a good bet that he quietly and good-naturedly bid all of them 'Break a Leg...theater's traditional Good Luck Omen...as he passed. Eddie heard the orchestra swing into 'By The Pale Moonlight as he started touching up his stage.make-up.

Up on the fly bridge, Bill McMullen called for both the houselights to dim and and power to his big carbon-arc spotlight. Brian Foy probably watched wide-eyed as the chief electrician twisted a rheostat, dimming the house lights all the way down, as he closed the arc light's knife switch at the same time. The effect worked perfectly...The sixteen opulently costumed dancers gracefully entered the stage, followed by a circle of diffused blue light, just as the houselights faded out, giving the impression that the moon was rising and that they were indeed dancing in the moonlight...

In certain 'Down Front' seats, the two flybridges...one on either side of the stage...were visible from the audience. Simple fix...both flybridges were concealed by vertically hung gauze curtains, hung close to it in such a way that the lights and fly bridges were both hidden from the audience.

The curtains were within just a few feet of Bill McMullen's spotlight, which was hazardous in and of itself, considering the fact that those big old carbon-arc spotlights generated about 4,000 degrees (Yep...you read that right) at the electrical arc between the electrodes...but the electrodes were actually pretty well isolated, and wouldn't be the problem. The huge amount of power the things drew, however, would. These lamps drew a tremendous amount of current...more than any building's electrical system was really designed for at the time. Because of this, a small defect could be a killer...a short could toss sparks around among all of the combustibles on a stage, igniting a firestorm.

It almost happened a couple of months earlier, in Cleveland, while Mr Bluebeard was touring. An arc light sparked, setting the curtains on fire, but that one was caught quickly and extinguished before any damage was done. And it's probably exactly what did happen that afternoon at the Iroquois, about fifteen or so minutes into the second act.

Bill McMullen was following the Pale Moonlight dancers with the blue spot, concentrating on that task diligently, when a couple of loud 'POP!!'s startled him at the same instant a bright blue flash lit up the wall behind the light...and the flash didn't entirely disappear...it just turned orange, and...

Bill jerked his head around and looked up and to his right, where a small flame was working it's way along the bottom edge of one of the gauze curtains that was hung to obscure the fly-bridge. These curtains were thin and lacy and burned fast, so what started as a fire the size of the palm of his hand quickly grabbed hold of the curtain and started climbing, just a dozen or so feet below hundreds of highly flammable, vertically hung scenery flats, supported by miles of manila rope. He knew he had to stop the fire.

**

Artist's rendition of the very early moments of the fire. Once those curtains got going, there was no stopping it with the entirely inadequate fire equipment that Bill Sallers had available to him. It only took minutes for the fire to reach the scenery flats stored in the fly gallery and 'Go for a hayride'. Both levels of the fly gallery were likely fully involved well less than five minutes after the fire started.

|

One of the post fire investigative photos, take from roughly the same point of view as the painting. The photo was taken from the Gallery...note the brass rails that were installed between the seats because of the Gallery's extremely steep pitch between seats.

The light bridge where the fire started is just out of view to the left of the stage. The building's main electrical switchboard was directly beneath the light bridge. You can see the Dearborn Street stage door, which I've labeled, at the rear corner of the stage as well as the tiers of dressing rooms immediately to the left of the stage door. Numerous cast and crew members as well as Eddie Foy's son escaped through this door before the backdraft and scenery collapse.

The scenery on stage would have become fully involved quickly as burning debris fell on it (And would have burned quickly due to it's lightweight construction.). Had the fire curtain worked properly and actually been fire resistant, it very well might have held the fire long enough for the theater to be evacuated, or at least to have significantly reduced the death toll, Unfortunately, while being lowered, the 'fire curtain' got hung up on a side light on the right side of the stage, leaving that side of the curtain 20 feet above the stage. On top of that, curtain was actually flammable, making it useless even if it had lowered properly.

Note the extreme heat and fire damage above the stage's proscenium arch. When the fly galleries and gridiron 'backdrafted', sending a fireball down onto the stage, then out into the auditorium, it rolled out from beneath the proscenium arch and across the ceiling, into the Gallery and Dress Circles, dooming anyone left in them. The useless fire curtain lit up and collapsed into the orchestra pit and first few rows of first level seats seconds later, about the same time the ropes holding the scenery flats aloft burned through and sent tons of burning scenery slamming into the stage, taking out the main switchboard and plunging the theater into flame-lit darkness.

The lack of debris on stage is notable as well. The scenery consisted of painted canvas stretched over lightweight wood framing, and would have burned fast and hot, even though the falling scenery partially snuffed itself by burying a lot of the fire when it hit the stage. It wouldn't have taken long at all for the entire pile of fallen scenery to re-ignite, and the debris would have burned fast, consuming the combustibles on stage in a matter of minutes. Engine 13's crew made quick work of what fire was left back/on stage once they took a hose line inside through the Couch Place scenery door.

**

|

Bill McMullen dived across the fly bridge and grabbed the curtain (Likely burning his hand while he was at it), tearing at it as he tried desperately to yank it down, and when that failed, he tried to beat the fire out with his hands. The fire climbed out of his reach in well less than an instant, causing both of his attempts to stop it to failed miserably. Even worse, as the fire climbed, it extended to the other curtains hanging near it, kicking a cloud of dark smoke ahead of it as it boiled upward, .