The Tragedies That Gave Us Fire Escapes

|

| They're there...but do we see them? |

Unnoticed and ignored though they may be by the general public, fire escapes become a huge part of life to those who live in the buildings they're installed on. For well over a century they've been used as patios, romantic meeting places, outside storage, clothes lines, and a quick way for teenage couples and BFFs to get to and from each other's apartments. The building residents are, however, far from the only people who've found uses for these iron stairways.

Note that in none of these examples...real-life or cinematic...were these fire escapes actually being used as, well, a fire escape. You know, to escape from a fire. Sometimes I think people have actually forgotten that their original and primary function was to allow the upper floor occupants of a multi-story building to exit quickly and safety in event of fire by allowing them to bypass the fire floor as well as the heat and smoke filled hallways and stairways above the fire. Once fire escapes became a legislated part of multi-story building construction and took on the form that became so familiar to everyone, they generally did exactly what they were designed to do, saving more than a few lives...

both civilians and firefighters...while they were at it. (Of course, they also had some drawbacks as well...we'll take a look at these, as well as some of the benefits when we discuss their history further along in this, er, 'learned tome')

The forerunners of those iconic tenements began popping up in the mid 1820s, but we can thank a potato famine and the people who would bring us green beer, pizza and, ultimately, Ferraris, for the huge influx of immigrants that occurred during the 1840s and 1850s. Many of them came from Ireland and Italy, and all of them had to be housed somewhere.

These buildings were all but built to burn, so there had obviously been more than a few fires in them, and there had probably been some fatalities as well, but what really amazes me is the fact that a major loss of life... ten or more...had never occurred when one of these tender boxes lit off at Oh Dark Hundred. Apparently luck had been shining on the tenement dwellers of New York, fire-fatality wise at any rate, over the last two decades or so.

Unfortunately, that good luck came to a sliding, screeching stop in February and March of 1860,

when at least thirty people died in a pair of tenement fires...and we're obviously here to take a look at those two fires, but first we need to take a look at the fire department that would have responded to them.

As you can likely well imagine, the New York Fire Department of 1860...160 years ago...was nothing like the present day F.D.N.Y. For one thing, it was an all-volunteer department, and wouldn't become a paid department for another five years. The then New York Fire Department boasted fifty engine companies, sixty or so hose companies, and seventeen ladder companies. All but one of the rigs were hand-pulled to incident scenes, and the great majority of the engines were hand-pumped rigs, though there were a few steamers in service by then. The steamers, BTW, were also hand-drawn with a single exception, that exception being a single self propelled steamer.

None of the ladder rigs had aerial ladders...the turn table mounted aerial ladder wouldn't become common for a bit over two decades. All of the ladders were hand raised, including the big 40 footers that were the longest ladders in the department.

These 138 companies were loosely organized under a central commission with a salaried Chief Engineer (What we call the 'Chief of Department today) who was elected from the ranks of the department.

The guys received alarms via citywide bells that rang the number of the fire district...there were eight districts...where the fire was located. I'm making an assumption here, but a citizen who discovered a fire had to run to the nearest bell tower or possibly fire or police station to turn in the alarm. There was a rudimentary telegraph system connecting the various bell towers, possibly the police stations, and a few of the fire stations.

The firehouses doubled as social clubs for their members, but most also had bunk rooms, and by 1860...and well before, in fact...duty crews slept at the stations most nights to ensure a quick turn-out on night calls. (We'll talk about this in a little bit in 'Notes)' The 'Bunking In' system actually worked fairly well, but there were problems. There were some...er...spirited rivalries between companies, and the occasional fight broke out on scene or enroute over who got to a hydrant first/ who would get first water on the fire, etc, to the oint that the actual reason they were there in the first place...that'd be the fire...kind of got forgotten in all of the excitement. Thing is, it often wasn't the firefighters themselves involved in these fights, but rather, the 'runners'...hangers-on who ran with the companies and who tended to be ruffians and hooligans and such...who caused the problems.

Don't let these problems give you the wrong idea...the firefighters of the old Volunteer Department were every bit as courageous and gung-ho as the modern firefighter is today, and they saved countless lives and, yes, saved a few buildings if they could get to the scene early and get water on the fire quickly...but there were also more then a few occasions where they lost entire blocks in a fire that would have been little more than a single alarm working fire involving a floor or two of a single building even ten years later, much less today.

Almost all of the 'New York' style hand engines had hose reels with 200 feet of 2.5 inch hose on them, and almost every engine company also ran a small two wheeled 'jumper' hose reel that could be either hand pulled or hitched to a tow hook on the rear of the engine. These little rigs usually carried anywhere between 400 and 600 feet of hose, and were called 'Jumpers because their size and relatively light weight allowed them to be 'jumped' over curbs and obstacles. The reels on the engine and jumper allowed the engine companies to lay in to the scene...if the hydrant was close enough...and get at least a couple of lines in service as soon as they could get water without having to wait for a hose company to get on scene.

The department, as noted above, also had 60 or so dedicated hose companies. The hose wagons were generally four wheeled carts with a single hose reel carrying from 600-1000 feet of hose. All of the hose was 2 1/2 inch hose, and in 1860 all of it would have been riveted leather hose. The members of the hose companies were likely tasked with stretching the attack lines and any additional lines that were needed., and I believe they also actually made the fire attack, assisted by the crews of the engines who weren't manning the 'brakes'.

Ladder rigs were long, open frame wagons carrying several ladders of various lengths. All of these rigs had a rear tiller...actually a second tongue attached to the also steerable rear axle...as well as the tongue and ropes at the front used to pull the rigs to the fire. The tiller, of course, was used to help steer the rig around corners on the narrow streets of the day, foreshadowing that most American of fire rigs, the tractor drawn aerial ladder.

Just shy of 2000 firefighters ran around 350 actual working fires every year, along with around 150 'other' alarms. (That's for the entire department, BTW...not for just any one single company.)

| |

|

Gas streetlights had been on for a couple of hours by then, casting circles of soft orange light around their poles, while that same glow lit the windows of larger businesses and of residences in the more affluent areas of the city...but not of the six story brick tenement at 142 Elm Street (Today's Lafayette Street).

That early in the evening there were likely a few candles burning in the twenty occupied apartments on the second through sixth floors, but no gas lights...as noted above gas lighting was not one of the amenities included with the apartments.

The building wasn't entirely without heat...the apartments did have fireplaces in the front rooms, as well as cook stoves, and coal fires were likely burning in at least some of the fireplaces, pumping coal smoke through the common chimneys that served each stack of six apartments and maybe barely warming the sharp chill inside the tiny flats. These fireplaces were far more effective at adding to the sulfurous cloud of coal smoke that hung over the city than they were at actually heating the iceboxes that the occupants called home.

|

| This is similar to the way each floor of the Elm Street building was laid out...four two room apartments with the narrow public hallway and stairway in the center of the building. There was a fireplace in each of the combination sitting room-kitchens, and the entire family shared the single bedroom. These buildings were thrown up quick and cheap and were uninsulated, making them ovens in the summer, and freezers in the winter. The fireplaces and cook stoves provided the only source of heat. The was also no lighting other than candles or oil lamps, so the stairways were pitch black at night (And not much better during the day). As the residents of the building at 142 Elm Street discovered, these buildings were also fire traps. |

The first floor of the tenement was divided into a pair of stores...a small grocery on the south side, and a bakery on the north...with the public entrance for the stairway that led to the apartments between the two stores. The building also had a basement...also likely served by the public stairway... that was used as storage by both first floor businesses, and the bakery had a large supply of hay stored in it's section of the basement. Sometime between 7 PM and 8 PM that evening, a fire started in the bakery's basement and quickly extended to that hay, filling first the basement, then the public hallway with heavy smoke that rolled into the narrow stairway and surged upward as if it was going up a chimney.

So no one was worried at first. Until heavy smoke pushed into the rooms, burning everyone's eyes and sending their lungs into spasm. One of the apartment's occupants may have opened the door to the hallway, and let hell into the room as heat and dark, toxic smoke instantly filled the room from floor to ceiling. By the time that happened, it was beyond too late.

The stairwell was already stuffed with smoke before the fire really got rolling...hay is notorious for producing heavy smoke, especially when it's smoldering...but then the hay lit up, and flames quickly rose to the basement's wooden ceiling...actually the underside of the first floor's flooring...and started rolling across it, heating everything in the room until it flashed over, sending flames surging up the stairs into the both the public hallway and the stairwell, cutting off escape well before most of the occupants even knew the building was on fire.

The heavy smoke would have quickly filled the building from the top down, surging up the stairwell and spreading across the upper part of the building, first rolling into the sixth floor apartments almost before the occupants could react, then 'mushrooming' and spreading downward, quickly charging the entire building with smoke. As this was happening, flames burned through the floor of the bakery, rising to and rolling across the ceiling and heating the interior of the small store until it, too, flashed over, blowing the bakery's front windows out and allowing flames to bend upward into the night sky, lighting Elm Street up like noontime.

|

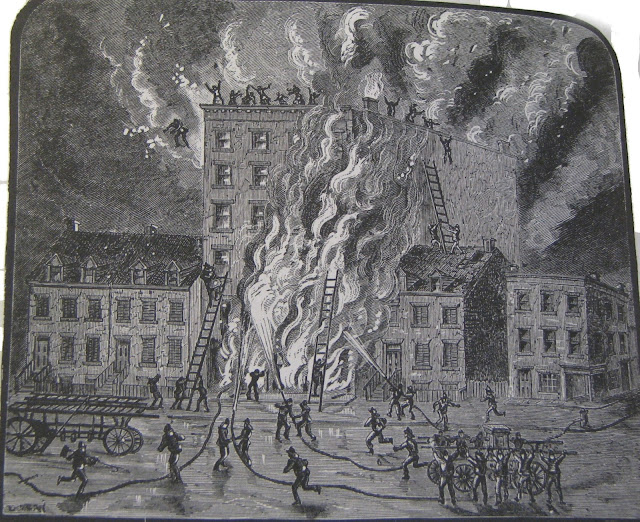

| An engraving of the Elm Street Fire, from 'Our Firemen:The History Of The New York Fire Departments From 1609 to 1887. I believe this same engraving appeared in the New York Times. This isn't entirely accurate, but it's still a good representation. People had already started jumping before fire department arrived on scene, but firefighters still managed to make some pretty spectacular rescues in the fire's early stages. Sadly, they weren't able to rescue at least 20 residents. |

Most of the occupants of those sixth floor apartments may have died almost before they knew anything was wrong, suffocating in their beds as the smoke mushroomed across the top of the building, but a few woke up to find their apartments filling with smoke. They stumbled out into the hallway to find they couldn't make it down the stairs and...somehow...climbed a ladder up to a roof scuttle, and dragged themselves out onto the roof. The problem was, 142 Elm was unusual as it wasn't built in a row of tenements...it was a single six story building in the middle of a block of two and three story storefronts. Once they got to the roof, they had no way down, other than to jump.

The occupants of the lower floors had time to either escape or die horrible deaths as they tried to. The stairwell was already stuffed with smoke and flames when one of them gathered their family and tried to make it out the door and down, only to be chased back inside as a dark, noxious, hot wall of poisonous death boiled into the room. The ones who didn't breath in a lung full of super heated air and collapse to the floor in agony did the only thing they could do...they headed for the windows and threw the sashes open. But they faced the exact same problem as the sixth floor residents who were now trapped on the roof...they had no way out of the building now other than jumping from the windows.

Most of the building's second floor residents would make it out by doing just that. A family of five named Wise would be the sad exception. The Wises lived in one of the front second floor apartments...probably the one over the grocery store...and the fire was probably well advanced when they became aware of it, because only the father and a 3 year old child made it out.

Wise may, in fact, have been one of the first people to become aware of the fire, but it was already too late when he and his family sprung out of bed as their apartment filled with thick, nasty smelling smoke. They didn't have time to dress, so they bolted from the bedroom still wearing their night clothes. Mr. Wise scooped up his youngest child...a three year old boy...and they ran for the door to the hallway, yanking it open, then cowering back as a storm surge of dark, super-heated smoke rolled in on top of them. Fire rolled in through the door and started running the ceiling as he turned and ran for the front window, yelling for the rest of the family to follow him as he threw it open.

When Wise threw the window open it created a draft that pulled the flames already rolling across the ceiling towards it, giving the five Wises only seconds to make it out. Wise held his son against him tightly as he looked out of the open window and down at the sidewalk twenty or so feet below him. Smoke was eddying around his body and his back felt like a slab of bacon in a frying pan as he climbed over the windowsill, only to find that it was just as bad there. Their apartment was above the grocery, but the entire first floor was charged with smoke...in fact, fire had likely cooked through the wooden floors of both stores by then...and smoke was pushing from around the store's front door and streaming upward. He was coughing and hacking on the smoke, and his son was crying...

I don't know if he dropped his son, or landed on him, but Wise couldn't stay astride the windowsill...he pulled his other leg across, turned himself so he was sort of sitting on the sill (This may have been when he dropped his son)...and pushed off. That twenty foot or so drop felt more like twenty stories as he fell, the second or so he was in mid-air seeming to last forever, and then his feet slammed into the sidewalk and his knees bent, and he may have even clocked himself with a knee as he tumbled, but he sprang up, bruised but otherwise unhurt, and looked around for his son, who he could hear crying. He quickly found him, lying nearer the street, one leg turned and bent unnaturally. The child wailed in agony as his broken leg dangled when his dad picked him up, but he had to get away from the building. Fire was boiling out of the front window of the bakery, only feet away,, and standing on the sidewalk in front of the building was like standing just inside the open door of a furnace. Wise turned and jogged out into the street and away from the building.

Someone came running up behind him as he moved away from the building, calling out and asking if all of his family had made it out. There was a sudden flaring glare above them as Wise turned to reply...he instead looked up, horrified, to see fire rolling up and out of the window he'd just bailed out of, cascading up and across the front window of the third floor apartment above his. By saving himself and his young son, he'd cut the rest of his family off from escape.

Even as he looked up, tears running down his face, the nearby district 5 fire bell began banging out the alarm...five bongs, a pause, then five more, repeated over and over, the distinct and unique tones of the fire bell crisp and clear in the cold night air, as the city's other bells joined in. Someone...either another occupant who'd made it out, or a neighbor...had run to the nearest police station or maybe the bell tower itself or, even more likely, Lady Washington Engine 40's fire house just a short block or so away at 173 Elm Street, to turn in the alarm, but it was far, far too late.

The alarm could well have been turned in by one of the seven member White family, six of whom were home when the fire broke out. Another one of them may have been the person comforting Wise as he stared at the flames rolling from his apartment window. Issac White and his boisterous and energetic brood lived in the other front second floor apartment...above the bakery where the fire started... and had also been chased out of bed as smoke filled their apartment, but there were very likely two differences in their escape, and one of them was a biggie

First, they smelled smoke and realized the danger earlier...a couple of them may have been awake, and, being over the bakery, smoke was probably pushing through the floorboards, alerting them to the fire sooner than the Wises across the hallway. They likely also tried to make it out through the hallway, and also got a face-full of heat and smoke as Issac White opened the apartment's door...but instead of leaving the door open as they retreated towards the window, he slammed it closed, and ordered his family to the front windows.

All six of the seven who were home...seventeen year old Gustave was absent that night...were coughing violently as Issac White shoved the window open. Smoke was pushing hard from around the bakery's front door, and likely pushing from around the window frame as well, streaming up the front of the building, and the window that the Whites were escaping from was directly in the path of all that smoke. White first helped his wife climb over the sill and, knowing they had only minutes, told her to 'Bend your knees when you land'...I'll drop Pauline (Their youngest) and Louis to you'...then watched as she pushed off of the window sill...he waited just long enough to see her land and leap up..

It was probably about then that eleven year old Louis possibly called 'DAD!!' and he looked back to see the faint outlines of two of his children...seven year old Pauline and eighteen year old Esther...crumpled on the floor, coughing violently.

'Hurry up! For God's sake, Zack,, Hurry up!' What Issac White couldn't see, his wife could...flames were rolling along the ceiling of the bakery. He held Pauline out of the window, and let go...he didn't have time to aim, but his wife sidestepped beneath the window and managed to catch Pauline...going down and landing hard on her backside as she did, but Pauline...who grabbed her mom tightly and sobbed in terror...was safe.

Issac got ready to pass Louis...who, at eleven, was pushing being as tall as his dad, and was already taller then both of his older sisters...out the window, but he handed the still semi-conscious Esther off to his dad. 'I can jump Dad' Louis told his dad between violent coughs. " 'Liza and I can help Esther down..." He looked over at his 20 year old sister Eliza. 'Sis, you go first..."

Issac looked towards the apartments door. The crack beneath the door was glowing bright orange, the apartment was so packed with smoke he could hardly see his kids only a couple of feet away.

" 'Liza, can you make it? He asked his daughter, helping her over the sill.. 'Yeah...' she answered, quickly gauged the distance to the sidewalk, then let go, her nightgown billowing and hair flying as she fell. Louis was already climbing over the window sill as Eliza landed perfectly, then rolled towards the street to get out of the way. He pushed off even as he climbed over the sill...out of the corner of his eye, he saw something fall, then saw their cross-the-hall neighbor going out of the window of the other 2nd floor front apartment. Louis landed hard but un-hurt, as his mom ran to help Mr Wise.

The temperature in the apartment suddenly spiked hard...Fire had burned through the upper part of the door, and was beginning to roll across the living room ceiling, reaching hungrily for the open window. Issac knew they only had a few seconds to escape. 'Esther, Honey, are you ready? He asked her even as he helped her over the sill. He didn't have time to get fancy...he turned her so she was facing the window, even as she nodded, coughing. White glanced down and let her go.

Issac pulled himself through the window and out into the cold night air even as he saw Luis and Eliza break Esther's fall, then drag her towards the street. He heard glass breaking as his feet pounded hard against the sidewalk, ...his knees bent and he went down on his right hip and side even as a quick, blast-furnace hot gust of air washed over him along with an orange flare that lit the sidewalk up...the front window of the bakery had blown, and fire was rolling up and over him. Issac crab-walked backwards frantically, hearing his wife and kids all calling for him.

After a couple of seconds that felt like the intake orientation class in Hell, he stood and jogged to the middle of the street, where Mr Wise and his terrified little boy had joined the rest of the White clan. His family was soot stained and dirty, and Esther was doubled over, retching from the smoke she'd 'eaten' inside the apartment...but all of them were alive. Little Pauline was trying to comfort the tiny Wise boy, whose dad had tear tracks running through the soot staining his face.

Flames were blowing out of the bakery and cascading up the building's front wall, joining with the fire now blowing out of the window that the Wises had just escaped from to reach as high as the fourth floor. The fire rolling out of the Wise apartment flared through the smoke pushing out of the grocery below it. Heavy smoke was boiling from the upper part of the building to roll upward into the night sky, bending northward as it did so. Even as they watched, the front window of the grocery blew out, and more fire boiled into the night. The street was lit up like noon-time, and even fifty or so feet away from the building, the little group had all but forgotten that it was cold outside.

The city's fire bells peeled in the background, and Issac couldn't help but think 'The boys won't have any trouble finding this one' as he asked 'Are we the only ones who made it out?'

"I think so..." He heard Mr Wise croak tearfully "Oh, my God, I think so..."

Though it wouldn't have mattered to him much at all...he'd just lost most of his family...Mr Wise was wrong. In the rear second floor apartment above the bakery, George Boedner had also discovered the fire fairly early as smoke filled his apartment, and had possibly, like Issac White, opened the door to the hallway to get a face-full of heat and smoke, then slammed the door and ordered his family to one of the living room windows, which looked out onto the rear yard of the tenement. They had an advantage that the occupants of the front apartments didn't have...a shed of some kind (Possibly the communal out-house) was hard by the rear of the building on that side, and he, his wife Frederica, and his sixteen year old son Henry (Very likely and almost inevitably called 'Hank') could just step out of the window onto the shed roof, then jump to the ground. His youngest child...tiny four year old Caroline...probably couldn't even see out of the windows, with their high-off-the floor sills, much less climb out of it, but he could just hand her out to one of the older kids.

The apartment was filling with smoke fast, and...like Mr White...he could see a flaring orange stripe beneath the hallway door. He shoved the window open and looked at his family.

'Hank, climb out onto the shed...Caroline come here honey...' He picked his daughter up as Hank quickly pulled himself through the window and stood on the sloping tin roof of the shed. 'Here...' he started to hand Caroline out to him '...Get your sis...WHOA!!!!'

The shed's tin roof rang like a bell, bouncing Hank Boedner off of his feet, as something...no some one...hit the roof hard and bounced, and only then did George see the clothesline rope hanging against the wall...the rope started swaying and swinging, and he heard someone above him, crying 'Francine...Oh My God, Francine...' Still holding Caroline, George leaned out of the window and looked up to see Bill Vopel, who lived in the fifth floor rear apartment above the bakery, climbing down the rope, hand over hand. His wife was lying on the roof on her side moaning. Hank, who'd missed being taken out by the plummeting Francine Vopel by less than a yard, was temporarily out of the ball game as he half sat, half leaned back on his hands, shaking his head back and forth as he tried to get the world to stop spinning in two or more different directions at once.

'Honey, I'm going to let you down on the roof' George told his daughter, then lowered her gently to the roof. 'Go over there' he pointed towards the end of the shed. She scampered in that direction only to be bounced off of her feet onto her bottom as Vopel dropped onto the roof. Hank, now recovered, looked at his dad, who said 'Go check your sister, I'll get your mom...' then turned to see fire cooking through the top of the hallway door and running the ceiling. Frederica, overcome by smoke, was on the floor, under the flames, her nightgown beginning to smoke. George crab-walked to her...God it was hot!...and grabbed her hands, back scooting across the floor, coughing, retching as the smoke thickened...then someone said 'I've got you' and hands grabbed his shoulders a someone else grabbed his wife and started dragging her towards the window.

Many of the members of New York's volunteer fire companies 'Bunked In' at their stations overnight, to give them a quicker response time, and Lady Washington Engine Company 40 was no exception. Their firehouse was located just over five hundred feet from the tenement, and I have a sneaking suspicion that the very first notification of the fire came in the form of frantic pounding at their front door.

Lady Washington's house...and indeed, the majority of New York's volunteer houses in 1860...enjoyed all of the bells and whistles that the tenements lacked. They very likely had gas lighting, and heat, and spacious, comfortable lounges and day rooms, and it's a good bet that, at 7:30 PM, that the duty crew was awake and playing cards or discussing whatever was discussed in a 1860 New York firehouse when they were interrupted by loud frantic pounding at the station's front door.

A couple of Engine 40's guys...or possibly a couple of the company 'runners' who were hanging out in the cheerful warmth of the lounge...were sent downstairs to see what all the noise was about...they yanked open the 'man door (As opposed to the rig's 'Exit Door') to have a couple or more people yelling 'Oh My God, they're still inside!!!' and "It's on fire!!' while pointing up Elm Street towards the burning tenement. One of the members or runners looked up Elm Street to see the sun rising twelve hours early in the wrong direction. I can just about bet the words 'Oh S***!!!' were yelled loudly even as their eyes went huge as they turned to yell up the stairs..

"Let's GO!!! We got one in full bloom right up Elm Street!!!!

Shoes clattered on steps as firefighters and runners bailed out of the lounge and down the stairs. There was no telegraph alarm system back then, but there was a telegraph system connecting the bell towers, and some of the stations also had a telegraph key. I don't know if Lady Washington's house was one of them or not...but if it was, one of the crew who was trained on using it immediately started pounding out a message to the bell towers.

As one of their number frantically pounded on the telegraph key, a couple of the crew pushed the big exit doors open as other members, along with runners, grabbed the twin tow ropes strung to either side of their rig's tongue, and started dragging the big white, blue, and gold leaf painted crane-neck style side-stroke hand engine out onto the street. Their firehouse was north of the burning tenement, on the opposite side of the street, so they swung out and to the left as they left the house. Even as their foreman shouted 'Start her lively, Boys!!!' they heard the District 5 fire bell's first sharp, clear 'BONG!!' as it began banging out the alarm.

| |

A beautifully detailed drawing of Lady Washington's rig, from Kenneth Holcomb Dunshee's 1939 book 'Enjine! Enjine!, which described in detail the development of hand-pumped fire engines in New York. The rig was known as a 'Crane Neck' engine because of the way the frame curved upward behind the front wheels...this allowed the wheels to pass beneath the frame and turn 90 degrees, which allowed the engine to be turned around in it's own length. The reel mounted ropes just ahead of the front wheels were the tow ropes the crew grabbed hold of to pull the rig...the tongue was used more for steering and for pushing the rig backwards than for pulling.

The red cylindrical structure with the company number painted on it houses the air chamber, which filled with water. forcing air into the top of the chamber. As the crew pumped, this trapped air would push additional water into the hose line on each stroke, which created a steady, solid stream of water rather than 'spurts' or a ragged stream. Air cylinders were, and indeed, still are, an integral part of all piston type pumpers...be they hand, stream, gasoline or Diesel operated.

The rig was built in 1856 by a company named James Smith, and had twin 8.5 inch diameter pump cylinders with 9 inch strokes, giving it a capacity of 265 GPM @ 60 strokes per minute. Of course, the faster the crew on the 'brakes' pumped, the more water they could move, so at, say, 80 strokes per minute, they could get 350 GPM out of the rig...but only for as long as the crew could keep that pace up. This is why engine companies of this era needed huge crews...as many as 40 to 60 guys (Not all actual members of the fire company...we'll get to that in Notes, too) would be queuing up to take their turns at the Brakes as the guys pumping them tired out.

The cylinder bearing the company number above the front wheels is the rig's hose reel, which carried 200 feet of 2.5 inch hose. The hose on the reels was primarily used when multiple engines were used to relay water from a distant water source to the fire. The engine on the water source...be it hydrant, cistern, or river...would hook up to the hydrant/drop it's suction hose into the water source, then pull all of it hose off of the reel, connecting to to their pumpers discharge. The next arriving engine would connect the line to their intake, then pull their hose off of and lay it out for the next engine,...the process would be repeated until they got water to the fire. There were stories of as many as thirty engines being involved in relay operations a full mile in length. Politics sometimes made this operation even more complicated...we'll get to that in 'Notes'.

|

| ||

An immaculately restored 1853 James Smith and Co hand tub just about identical in design to Lady Washington Engine 40's rig, right down to the front mounted hose reel. This rig is owned by the Fire Museum of Maryland, and was built for the Brooklyn Fire Department in 1853. The Storm Engine Company, of Babylon, New York bought it used and placed it in service in 1881. I'm not sure when the Fire Museum of Md. purchased, but it was pictured in the 1939 book Enjine! Enjine!, referenced above, as a museum display. It's absolutely awesome, IMHO, that this rig has been maintained all these years...and yes, she's fully functional to this day.

There were pretty capable rigs for the day, capable of pumping around 265-350 or so GPM with a full crew working the brakes at full tilt, which would be around 60-80 strokes per minute. The problem was the crew could only keep that rate up for between five and ten minutes at best, even less if they were pumping harder. .This is why engine companies from this era required huge crews, so a fresh crew was ready to take over when the working crew grew tired and needed a break. Also, the crews usually didn't take breaks as a group...each person on the brakes would drop off as he became tired, to be replaced by one of the fresh men waiting their turn.

|

Today, the Officer In Charge of the first in engine company, seeing trapped residents hanging from the windows of a well involved multi story, multi family dwelling as he rolled up, would break out into a cold sweat even if he was riding right seat on a brand new example of the newest, most advanced pumper on the road, with an equally new, equally advanced 110 foot tower ladder rolling in right behind them, and the rest of a full first alarm commercial/multifamily dwelling assignment only minutes away. Needless to say, the foreman and crew of Lady Washington Engine 40 had it far, far worse than that modern fire officer.

While they did have hose...almost every N.Y.F.D. engine carried a reel with 200 feet of 2.5 inch hose and a couple of play pipes and nozzles, plus they had another four hundred feet of hose on the jumper, along with another playpipe...they didn't carry water on board (Booster tanks on fire apparatus weren't even a concept yet, and wouldn't become common for nearly 70 years.) and they didn't carry any more hose or any ladders. Hose Companies were separate companies, with their own houses, as were ladder companies.

The nearest hose company...Atlantic Hose Co 14...was quartered about a half mile east at at 3 Elizabeth Street, and the nearest hook and ladder company...Eagle Hook and Ladder # 4...was an equal distance away to the southeast at 22 Eldridge Street. Both companies were a good seven or eight minutes away with the crew running hard, feet pounding on cobblestones as they dragged the rigs behind them, and neither had the advantage of having the fire staring them in the face as they came out of their stations. They had to 'Chase the glow' to find the fire's location. Lady Washington's guys would be on their own for a long, long eight minutes or so.

Lady Washington's crew did have a hydrant though, at Elm and Grand Streets, just north of the fire. Lady Washington's crew started scrambling. Their foreman shouted up to the people trapped in the building to hang on, that help was on the way, then, over the rumbling crackle of flames, and peeling of the fire bells, started barking orders to his crew.

"Lets get on that hydrant and get a line in service!!" Then to the crew on the jumper...' Get some more line off for a second line!!' This taken care of, he looked at two of his firefighters...Danial Scully and one other firefighter.. "Dan...you two haul ass around back and see what we've got on the backside of this thing...

The two firefighters disappeared down an ally between a pair of storefronts as the hose reel sang, spinning fast as the crew dragged all 200 feet off of it. One member cut it at the first coupling, grabbed a hydrant wrench out of the engine's tool box, and dragged the female end towards the hydrant as another grabbed the male end and quickly spun the coupling onto the rigs's intake. Another crew coupled the rest of the line to one of the pumper's two discharges and screwed a playpipe and nozzle to the line's business end, while the rest of Lady Washington's guys unfolded the brakes from the 'traveling' position, pulling them down and out to the rig's sides.

"Ready for water!!" The hydrant man slapped the hydrant wrench onto the operating nut on top of the hydrant and spun it, water surged through the hose line, swelling it as it rushed into rig's tank as twenty guys...ten on each side...grabbed hold of the brakes, waiting for the water to fill the tank so they could prime the pump.

"OK...Work her boys!!!" The rig started rocking as the crew slammed the brakes up and down, shoving water through the attack line, then a half inch stream of water spurted from the nozzle and blasted into the flames roaring from the bakery windows...

As the first stream bored into the fire, the jumper's reel sang as a second line was pulled, cut at a coupling, and connected to the engine's second discharge. Another playpipe was spun onto that line's business end, and the call 'Ready for water on the second line!! was called back to the engine. A firefighter at the rig spun the discharge valve open and a second stream bored into the flames.

With the guys on the brakes going all out, they may have been pumping as many as 80 or so strokes per minute, or about 350 GPM from the pump's twin 8.5 inch diameter by 9 inch stroke cylinders, or about 175 GPM from each of the two lines. They may have even darkened the fire in the two stores down a little bit, giving the very false impression for a hopeful minute that they were getting ahead of it...but the fire was already way ahead of them, and they knew it. The stairwell and public halls were fully involved on all six floors, and the fire had rolled into apartments on at least three floors.

Around on the backside of the building, fire had cooked through several sixth floor rear windows already, and smoke was pushing from several other windows as Dan Scully and the other fire fighter ran up to the rear of the burning tenement. The communal outhouse was hard by the north side of the rear wall, and several people were on it's roof, but even worse, there were people leaning out of a third floor window on the south side of the building, smoke billowing around them as they screamed for help.

'Give me a boost up on that roof, then haul ass back around front and tell 'em we need men and ladders back here!' Scully said, then yelled up...to both the people on the shed roof and the ones at the window... "Hang on!!'

Scully's partner made a stirrup with his hands and boosted him upward as he pulled himself over the edge of the roof, looking at the four people standing, and in one case, lying on the tin. One, a boy of about sixteen or so was holding a little girl. A couple of feet away from the kids a man was kneeling next to a woman who was lying on her side, moaning in pain. A clothesline was swaying in the breeze...which was blowing towards the front of the building...as it led upward to a fifth floor window that was just beginning to show fire.

'My Mom and dad are still in there!' the teenager yelled, pointing at an open second floor window The smoke rolling from the window was tinted orange. Scully knew what his next move had to be. 'I've got 'em' he told the youth, then ran across the roof and looked through the window. He could see the garish orange glow of flames through the smoke, which was banked down to within two feet of the floor, boiling out of the window like it was being pushed by a pump. He could see movement...

Mrs McCarrick wasn't a tiny woman, but thankfully she wasn't huge either....Scully swung her around behind him, yelling for Mr. McCarrick to climb out onto the ladder. Scully then turned and helped McCarrick out of the window as, out of the corner of his eye, he saw the firefighter on the ladder next to them grab his wife, almost over balancing as he did so. Rather than swinging her onto the roof he helped her find her footing on the ladder in front of him, then guided her down as he climbed down the ladder.

Even as Dan Scully and his crew, along with Ladder 4's crew, were getting the Boedners and the McCarricks out of the building, more companies were rolling in. As the hose companies arrived, their crews laid lines from more distant hydrants, meaning that as the engines were dragged on scene, their crews had to set up relay operations to get water to the scene. As many as three or four engines would be lined up 200 feet apart, pumping into the next engine's intake, each relay supplying a single stream. Twenty man crews manned the brakes on each engine while anywhere from thirty to sixty men on each waited their turn to take over for two to three minutes at a pop...that was as long as anyone could last pumping the rigs before they needed to rest for a few minutes. As many as six or eight streams were probably playing on the fire, but sadly all of this effort was all but futile, as the only effect those multiple streams seemed to be having on the fire was to annoy it a bit.

Meanwhile more ladder companies...the city had 17 of them at the time and at least three or four responded to the scene...rolled in behind Ladder 4. Even as the more streams were placed in service, 'Truckies' slid the heavy wooden ground ladders out of their racks on the long, hand-pulled ladder rigs, and hustled them to where they were needed on the front and rear of the building.

It was a hectic, boisterous, and active scene, and the noise was horrendous. Disjointed calls of 'Pump! Pump! Pump! at each engine, timing the rocking 'CLANK-CLANK! of the brakes, were overshadowed by shouted orders, screams for help, and the rumble of flames.

These later arriving companies were making another desperate rescue on the front side of the building even as Dan Scully and his crew raced against time to get the McCarricks out of their rear apartment. Bill North, his wife, and their three kids lived in the third floor apartment directly above the Wise apartment and the grocery, and now the couple was leaning out of a smoke-puking third floor window, yelling for help, their kids cowering behind them.

Several firefighters quickly sized up the problem, a plan very similar to the one Dan Scully came up with was hatched on the fly, and orders were shouted. Several firefighters ran into the building hard by the south side of the burning tenement and up the steps, quickly finding their way to a front second story window. Another crew began setting another forty footer against the wall of the tenement as the Norths begged them to please hurry. The top of the ladder slapped bricks just below and to the left of the window the Norths were hanging from, between it and the corner of the building.

A firefighter leaned out of the window of the building next door as two other firefighters quick-climbed the ladder, making it bounce as they bailed up the rungs. Fire was rolling from the window Mr Wise had escaped from and cascading upward, across the window next to the one the Norths were framed in while the window directly below them was painted a livid, flaring orange...only Divine Intervention, luck, or a little of both had kept it from blowing, the same elements apparently keeping the fire in the hallway from cooking through the Norths' hallway door.

'Give me the kids first!' the firefighter at the top of the ladder called to the Norths. He could feel the heat radiating through the orange-tinted second floor window directly below the trapped family. He looked below and to his left 'You guys ready?!?, getting a 'Yeah, go!!' The first child was handed out, the firefighter at the top of the ladder turned and handed him down to the firefighter below him, then twisted back around the grab the second child. As he was doing this, the second firefighter swung the first child over the the firefighter leaning from the second floor window of the building next door, who quickly pulled him inside the window. This process was repeated twice more, with all three firefighters hustling, the firefighter in the building next door telling each child to wait behind him as he pulled them in the window.

Mrs North was next....she climbed out onto the ladder...unlike the kids, she was too big to swing across. There was a cracking next to them, and fire boiled from one pane of the other window in the Wise apartment. The firefighters nearest the top of the ladder had 'leg-locked' the ladder, passing one leg around a rung and hooking that foot beneath the rung below it so he could use his arms to swing the kids over the firefighter next door. He kept the leg lock in place and had her climb down to him, then grasped her around the waist, twisted, and passed her down to the firefighter below him, who quickly started carrying her down the ladder.

|

| A firefighter applying a leg lock to a ladder. This allowed him to have his hands free so he could handle hose and tools and make rescues. There are actually a couple of ways to apply a leg lock...the firefighter can also lock his foot beneath a rung rather than the beam of the ladder, which is the method I've seen used most often. |

Mr. North was already climbing out of the window, even as the firefighter released the leg lock...as he pulled his leg back up and over the rung, more glass fell from the window of the Wise apartment, and more flames rolled into the night, causing him the forget that this was a Winter night. Unknowingly parroting Dan Scully, he asked Mr. North if he could make it down, to get an enthusiastic 'Yes!, even as Mr. North all but climbed over him...the two men scampered down the ladder. Just before they made it to the sidewalk, the entire building shuddered as if someone had tapped it with a giant sledgehammer, and fire blew from the second floor windows of the building next door...a sight that filled him with dread until he saw the three kids hugging their mom as the two firefighters who'd been in the building next door led them across the street. Both windows of the Wise apartment were vomiting fire and, as if in sympathy, the smoke boiling from the North apartment turned orange as flames rolled from those windows as well. The Norths were likely the last people to get out of the building alive.

Several firefighters laddered the steeply pitched roof of the building next door to the tenement's north wall, then pulled another of the big 40 foot ladders up to the lower building's roof. Then, working as quickly as the roof pitch would allow, they dragged the ladder up to the roof's peak, and set it against the wall of the tenement. If they could have set it straight up and down it might would have barely reached. But to be climbable, of course, it had to be at an angle...so when the ladder was raised, even at the steepest angle possible to climb, it was a good ten feet short of the tenement roof.

The fight to save the block may have been helped along by the Exempt Engine Company...an engine company comprised of semi-retired firefighters which was equipped with not one but two steamers, one of which was a big self-propelled rig with a capacity of around 800 GPM. The Exempts only responded on general alarms, and it's a good bet that at least one of these steamers responded to Elm Street when the general alarm was called for.

Of course with this rig's cold-molasses-like top speed of between two and five miles per hour, it could have taken as as long as 40 minutes to make the mile and a third between The Exempt's firehouse at #4 Centre Street and the fire scene. When they finally got on scene, they may have taken over the hydrant Lady Washington Engine 40 had been on (If Lady Washington's guys let them...more on the weird politics of those early volunteers in 'Notes'). But if the steamer did respond, and if they were allowed to take a hydrant and flow water, they would've been able to supply multiple lines all night long if necessary, and most of the battle to save the block would have been won.

|

| A drawing of a big Lee and Larned Self Propelled steamer of the type that Exempt Engine had in service and possibly responded to the Elm Street fire with on the general alarm. This thing was a beast! It weighed 11,000 pounds and was capable of pumping 800 GPM as long as it had fuel. The rig didn't require horses or men to get it to the scene or pump it...but it was also said to be slower than frozen molasses running up-hill. The rig's rotary gear pump was rear mounted...note the air chamber just behind the fellow in the rear of the rig. This guy would have been the rig's engineer, who was in charge of operating both the steam engine and the pump...oh, and the brakes. Yep...you read right...driving this behemoth was a two man operation. The driver steered, while the engineer handled the brakes...getting stopped required planning and team work. The Exempt rig's slow speed helped a bit there, but getting to a scene more than a mile or so away could be a half hour or longer trip. On the night of the Elm Street fire, the rig was responding from the Exempt's fire house at #4 Centre Street, about a mile and a third north of the scene, so at it's blazing top speed of between two and five miles per hour, it would have taken anywhere from fifteen to about forty minutes to get to the scene. That being said, if the rig did respond to Elm Street, it probably saved the block. |

The tenement was on the ground by about 11 PM, and probably burned a good portion of the night as the crews continued to throw water on it, but then the steamer would have been a true Godsend, able to pour water into the flaming, smoldering ruins for hours on end without breaking a sweat.

Keep in mind that the tenement wasn't the only damaged building they had to overhaul. There were at least four other structures damaged. It's a pretty good bet that there were crews there for most of the night.

The investigation and search for bodies didn't start in earnest until the next morning. Portable lights powerful enough to illuminate an entire scene were still a couple of decades away at best (And lights both portable enough and powerful enough to be taken into nooks and crannies while searching along with generators portable enough to be taken to scenes, were even further in the future). They also had to wait for the building's ruins to cool down enough for them to begin digging.

It very likely took at least a couple of days for investigators to locate and remove all of the bodies (If they, indeed, did find all of them), but it was obvious before they started, just from the number of missing, that the death toll was bad. The New York Times published a pretty sensationalized article the very next morning estimating the death toll at 30 (Which I think is actually more accurate than the official death toll of 20...more on that in Notes) and the public took immediate notice

Several articles had been published over the last couple of years decrying the unsafe and horrible living conditions residents of these early tenements faced, and a horrific fire such as this had been predicted for years.

A Coroners Jury was impaneled, and came to some immediate conclusions about the fire. While an actual cause was never determined, it was determined that the building's poor design and lack of fire safety contributed directly to the loss of life. Building owner Edward Waring was found to be directly responsible for the building's poor condition, but I could find no record of what, if any action, was taken against him.

It's a good bet, however, that no action was taken against him at all. Waring was likely fairly prominent and more that a little wealthy, and wealthy building owners very frequently skated on charges of negligence and worse in multiple fatality fires back in that era, an outcome that occurred well into the 20th century, as I've already recounted in a couple of posts. On top of that, Waring's building, sadly, was not only far from being an isolated case, it was actually the norm for tenements of the day.

With the Coroner's Jury opinion and suggestions backing them up, the public demanded action from the city, but local governments had (And to this day still have) a tendency to react at the approximate speed of a turtle going uphill. You know the drill. While some discussion very likely did take place concerning a fix for the city's overabundance of firetraps, nothing was actually done. See, the city's Common Council (What we'd call 'City Council' today) found they had a problem...they weren't authorized by state law to enact any kind of fire safety ordinances.

This, of course, meant that the Common Council had to get the state government involved. This caused things to move just as 'quickly' as you might think it would've. On February 10th...eight days after the fire....a bill was introduced to the State Legislature that would empower the city's 'Common Council' (What cities big and small call the 'City Council' today) to draw up, enact, and enforce ordinances.

While

awaiting passage of that law, New York's Common Council appointed a committee to look into the problem and suggest solutions. Then the Council studied and discussed the various suggestions that the committee came up with, and drew up some some pretty ground-breaking ordinances requiring all tenements to be equipped with fireproof stair towers and/or

fireproof exit stairways accessible from each and every apartment. Aaaaand, nearly two months after the Elm Street fire, that's all that had been done.

The problem was, of course, that until the law authorizing the common council to enact and enforce them was passed, the new ordinances weren't even worth the paper they were written on. Again, they had to wait for the State Legislature to give them legal authorization to enact the ordinaces, and waiting for the state to act on anything was like taking cold molasses, putting it the freezer, then trying to get it to flow uphill.

Unknown to anyone (And to everyone's ultimate horror), the February 2nd fire was just the first horrific tenement fire that would occur during the cold winter of 1860. OK...the second one was actually during the early Spring...March 28th to be exact, a week shy of two months after the Elm Street fire.

The winter of 1860 was likely beginning to wind down along with the month of March on the evening of March 27th, and as Tuesday the 27th became Wednesday the 28th, everyone in the four story wooden tenement at 90 West 45th Street, about three and a half miles north of the fire scene on Elm Street, was curled up in their beds, asleep.

The tenement at 90 West 45th Street was, if possible, even more of a fire trap than the building on Elm Street. It was one of four flat roofed, wood frame four story tenements...84-90 W 45th Street...that were thrown up quick and cheap in 1853. The four tenements were just shy of twenty feet wide by forty or so feet long. A combination grocery/liquor store was located on the first floor of 90 West 45th...the fire building...while a pair of three room apartments were located on that building's second, third, and forth floors. The buildings at 84-88 W 45th had apartments on all four floors rather than a first floor store.

Each

apartment in the fire building featured a main

living/cooking/dining room with a fireplace. and a pair

of tiny bedrooms

|

A good approximation of the floor plan of each of the 45th Street tenement's floors. Each floor had a pair of three room apartments, with the public hall and stairway on the right side of the building. The dotted square next to the stairway is the possible location of the roof scuttle, though it could well have been more towards either the front or rear of the building.

Like the Elm Street tenement, that hallway would have been pitch black at night even when it wasn't stuffed full of smoke...these buildings were the absolute definition of 'Fire Trap'.

|

|

| Detail map of the area surrounding the W. 45th Street fire scene. Unfortunately the map stopped at 46th Street, so I couldn't mark the exact locations of H&L 8, Hose 31, or Engine 1. |

Each of the four tenements had a public entrance toward the right side of the building (Separate from the store entrance on the fire building)) and a single three foot wide stairway that opened into a public hall on each residential floor. The first floor public hallways in the buildings at 84-88 W 45th likely also had back doors opening into the rear yard. Again, like the Elm Street tenement, there were absolutely no nods of any kind given to fire safety.

There were scuttles leading to the roofs of the buildings, but only one building...88 West 45th...had a ladder that allowed access to the roof through the scuttle.

Five of the six apartments in the fire building were occupied, all by large families. Timothy Nolan and his wife and four kids called the 2nd floor rear apartment home, while a widower named Kearney lived in the 2nd floor front apartment with his two children. On the third floor we had the six members of William Irving's family in the front apartment and Thomas Bennett, his wife, and four kids in the rear apartment. In the Bennett apartment, Mrs. Bennett's sister Jane McNalley was visiting, and was staying overnight.

The front 4th floor apartment was unoccupied, while Andrew Wheeler, his wife, and their four kids lived in the rear 4th floor apartment.

Several of the fathers worked for New York's Sixth Street Railroad Company, and two of them...Thomas Bennett and Andrew Wheeler...were working a midnight shift, meaning that they weren't at home and that their families were slumbering peacefully in their absence when, sometime around 1 AM, someone slipped into the unlocked public entrance of 90 W.45th, opened up a closet beneath the stairs, set the contents of the closet on fire, then slipped back out into the night.

If the arsonist meant for the fire to take the whole building...and it's a good bet he did...he probably left the closet door open, but even in the unlikely event that he closed it, it wouldn't have taken long for the flames to have cooked through both the flimsy door and the steps themselves, and then, just as it did on Elm Street nearly two months earlier, the stairwell acted just like a chimney, drawing heat and smoke upward to the forth floor, where it immediately started mushrooming.

What happened next was a near-repeat of the Elm Street fire, as smoke and heat filled the cock loft (Space between top floor ceiling and roof) and fourth floor chock-full in only minutes even as flames stair-climbed the wooden staircase. Of course, all of the heat and smoke didn't go up the stairwell, as the fire would have rolled across the hallway ceilings on each floor as well. Keep in mind that these were narrow little hallways...about five feet wide, and the stairwell, which was filled with first heat and smoke, and only minutes later, flames, took up three of those feet. Fast rising flames would have lapped over into the hallways and started running the ceilings as soon as the flames themselves reached each floor, and this would have happened from the bottom up, only a minute or so after the heat and smoke reached the fourth floor hallway and started mushrooming. This would have blocked any possibility of escaping down the stairs long before any of the occupants discovered the fire.

The lower floor apartments themselves would have stayed smoke free for a few...a very few...minutes as smoke and heat 'mushroomed', filling the building from the top down to meet up with the flames climbing the stairs. It was a toss-up as to who discovered the fire first...the Wheelers on the 4th floor, or either the Nolans, or Mr. Kearney and his kids on the second floor, but my bet's on the Wheelers, and the reason why is also the reason that this fire was a near repeat of Elm Street.

The fire started in the first floor hallway...next to the apartments...rather than the basement, beneath them, as it had on Elm Street, so for the first few minutes of the fire all of the heat and smoke went straight up the stairwell rather than pushing up through the floors and walls. This kept the second floor apartments from filling with smoke for just a little longer than had happened two months earlier, allowing the Nolans and Kearneys to sleep in innocent and ignorant bliss for a few minutes even as the Wheelers were discovering, to their horror, that their apartment was filling with smoke.

Of course, there is another, even more likely scenereo that would have been more merciful if no less horrible. Mrs Wheeler and her kids could have also suffocated in their sleep, never realizing the horror that overtook and killed them.

If the Wheelers did wake up and try to make it out, Thomas Bennett's wife, her sister, and the Bennett children were possibly awakened a floor below them, in the rear third floor apartment, by what sounded like a thundering herd pounding across the floor above them as the Wheelers ran out of, then back into their apartment. It's even possible that the Bennett apartment hadn't filled with smoke as thickly as the Wheeler's top floor apartment yet, but there was still smoke hanging, evil and malignant, when the Bennetts woke up, heavy enough to snap all of them wide awake and send them, like the Wheelers in the apartment above, tumbling and rushing for the door.

Mushrooming smoke had banked down enough to fill the third floor hallway by the time the Bennetts woke up, and when Mrs. Bennett yanked the door open, she was met with a fast thickening wall of smoke and heat that rushed into the apartment like a vaporous tidal wave, filling the tiny living room before she could slam the door on it. I'm of two minds as to whether she did get it closed or not...but we'll get to why in a second. Whatever happened in the Bennett apartment, we know for sure that they did wake up, because Mrs. Bennetts sister would make it out...which is also why I wonder about the front door.

In the front third floor apartment, William Irving and his family likely woke up in much the same way as the Wheelers and Bennetts, coughing and hacking and wheezing on the smoke pushing into their apartment. And, also like the other two families, they rushed to the front windows when they found the hallway blocked by smoke and flames. They shoved the windows open and looked down at the sidewalk...thirty or so feet below them.

When they looked down they very possibly saw Mr. Kearney lowering his two kids out of a front window of his second floor apartment...he probably leaned out of the window, stretching his arms downward as he held each child's hands, trying to get them as close to the ground as possible, before he let them drop. Once he was sure they were safe, while yelling at them to 'Stay right There!!. he climbed out of that same window and dropped to the sidewalk in front of the building, gathering his two kids and getting them away from the fire. We know for sure that the Kearneys as well as the Nolans in the second floor rear apartment made it out uninjured, and likely did so fairly early in the incident. My bet is that the Irvings called to Mr. Kearny to help them, or to call the fire department or just screamed 'Oh, God, please help us!!!, but whatever actually happened, Mr Kearny quickly realized that there were people trapped in the building.

Or, maybe some of the occupants of 88 W 45th...the tenement next door to the fire building...were awakened by the commotion and, realizing that the building next door was burning like a torch, evacuated their own building. And if that's what happened, it's a good bet that some of them started going through the other two tenements and getting people out. We'll never know for sure just how the the residents of the other three tenements found out about the fire, but we do know that everyone in those three buildings made it out without even breaking a sweat.

Of course, as residents made it out of the buildings, they had another problem on their hands...Unlike Elm Street, there was no fire station near the scene on 45th street, so someone also had to haul ass to either a police station or the bell tower to report the fire, which had been burning for as much as ten or fifteen minutes before the citywide fire bells began banging out the alarm.

Volunteer firefighters who were pulling duty at the stations rolled out of bed, pulled clothes on, and tumbled down stairs. Other firefighters unlocked the big exit doors and pushed them open, as even more firefighters and runners, coming from home, joined them at the tow-ropes, and the crews dragged rigs out of the exit doors, looking for a tell-tale glow or column of smoke..

The fire likely wasn't hard to spot. The building was all frame, and frame buildings tend to burn hot, fast, and bright. Fire had likely cooked through the building's fourth floor windows, and very possibly the windows of the Bennett apartment on the rear of the third floor. On top of that, fire had likely cooked through the roof, ignited the pitch-soaked canvas roof covering, and started advancing across the roof like a brush fire, quickly spreading southward to the roof of 88 W. 45th, next door.

|

Engraving of the 45th Street fire that appeared in the New York Times. The fire building's fully involved, and the fire is spreading southward...to the left...into 88, 86, and 84 W 45th. Ten people died at this fire.

Engine 46's steamer is shown on scene...but the rig pictured looks nothing like 46's Lee and Larned rig, leading me to wonder just how accurate the rest of the engraving is. If anything, the steamer in the engraving looks like Exempt Engine's self propeller, which didn't respond to the scene as far as I know.

Engine 46's Lee and Larned 300 GPM steamer was instrumental in stopping the fire from taking most of the block, and confining the fire to the upper floor or two and roof of 84-88 W 45th.

|

At 8th Ave and 48th Street, about a half mile north and slightly east of the fire, Hook and Ladder 8's crew quickly spotted the orange-tinted smoke column urging skyward to their south, and started dragging their big open frame ladder truck down 8th Ave, with Hose 31...quartered right around the corner and therefore directly behind Ladder 8's quarters...and Hudson Engine Co 1, whose house was a half a block up 48th Street, right behind them.

As they waited for a full crew to show up, the rig's engineer took a lighted taper from the stove and shoved it into the tinder and kindling laid on top and around the coal in the fire box, lighting it off. The ten or so minute run to the scene would be just about enough time to get steam up in the boiler.

As soon as enough men to pull the steamer showed up, they took their places at the tow ropes of both the steamer and the four wheeled hose wagon and dragged the rigs out of the station, the hose wagon leading the way.

Even as the crews of Ladder 8, Hose 31, Engine 1, Engine and Hose 46, and several other companies ran their rigs towards the fire, someone (A part of me wonders of it was the actual arsonist, but it could also have been one of the occupants of any of the four buildings as many of the men were employed by the railroad.) ran into the Sixth Ave Railway shops and shouted that 'The house at 90 West 45th was on fire!!!'

Andy Wheeler and Tom Bennett likely looked at each other, shouted near simultaneous 'Oh My God!!'s, and took off at a dead run. The fire was likely already lighting up the night sky by then, filling them with dread as they ran through the empty streets. The city fire bells began tolling even as they ran, as if to confirm what they were seeing.

Whoever ran into the shops and notified them did so early enough that the two men beat the rigs to the fire...they could see flames rolling from the upper floor windows for a couple of blocks as they ran up 45th street, and both of them tried to make it into the first floor public hallway when they got there. One of them yanked the door open (Probably burning his hand as he did so) to be met by a face-full of fire and a furnace-blast of heat as flames rolled out of the doorway and bent up and out, reaching to the third floor In that instant they saw that the hallway was burning from top to bottom, the stairs nothing more than a flaming framework, and knew that they couldn't get to their families.

Above them, the Irvings were hanging out of the windows of the third floor front apartment, yelling for help, and this gave Tom Bennett a little bit of hope. If the Irvings were still alive, maybe...

...But his hopes had already been dashed. In the third floor rear apartment, even as the two men ran up, the Bennetts were beyond desperation, into something beyond terror as flames roared into the apartment from the hallway. From the little I could find out (And trust me on this, it was very little) I think Mrs. Bennett was startled by the wall of smoke that rolled in to the apartment, and she and her sister grabbed the kids and left the door open as they ran to the windows, shoving one or maybe both of them open. This created a draft, that pulled the fire right on top of them as it rolled towards the open windows.

All five of them cowered from the flames, leaning out of the two rear windows until their night clothes began scorching. One of the kids started screaming as his shirt caught on fire. And in desperation, Jane McNalley climbed over the window sill and, as her sister and nieces and nephews screamed in pain and terror, jumped, injuring herself horrifically as she slammed into the backyard's packed earth. William Holden, who lived behind the burning tenement, on 46th Street, had been awakened by the screams of terror coming from the building (He would state later that he thought some of the husbands were beating their wives again (?!?!) ) and looked out of his window just in time to see her jump. He quickly dragged on some clothes, rushed downstairs and out of the back door of his own building, and reached the injured woman about the same time as as several neighbors (Among them Andrew Wheeler) along with some firefighters from the first arriving companies. They quickly carried her away from the building, to a near-by Police precinct. From there she was taken to the hospital with severe burns as well as a broken femur.

She probably jumped only a few minutes before the first rigs rolled onto the scene. Ladder 8's crew wasn't the first rig on scene, but they weren't far behind the first arriving engine and hose companies, and they were the first arriving ladder company. The glow became progressively brighter and larger as they neared the scene, and when they swung left onto W 45th, it looked like the sun was rising about five hours too early. The entire upper part of 90 W. 45th was a seething, crackling mass of flames rolling twenty or more feet above the burning roof, and flames had spread across the roofs of at least two of the other tenements, and possibly all three. They could look up, through the fourth floor windows of 84, 86, and 88 W 45th and see burning, melting tar dripping downward into the fourth floor, the top floor windows of 88 were likely already glowing orange. On top of that, flames could also be seen in the third floor windows of #88...fire had burned through the party wall between the two buildings.

Their was probably a hydrant fairly close to the scene, and the first engine had probably taken it, and gone in service, so there was at least one stream flowing water as Ladder 8 rolled up, but that one stream was all but pointless. Hose 32 and Engine 1 possibly laid in from a second hydrant on the way in...'Bringing their own water'....or they may have taken water from an earlier arriving engine, and another stream or two was soon boring into the flame. Even as the crews of Ladder 8, Engine 1, and Hose 32 rolled in and went to work, they took one look at the building, and at the flames walking across the roof and showing in the windows of #88...and someone very likely said something to the effect of 'We're gonna lose this whole f***ing block!'.

Fire had spread from first floor to roof in the stairwell of the original fire building, and heavy, boiling smoke was pushing from between the siding boards and churning from the front third floor windows, all but hiding the terrified people hanging out of them. Ladder 8's crew saw them through the billows of smoke, could hear them calling for help, and swung into action. They pulled a wooden ladder (Probably a 35 footer) from the rig and quickly raised it to the third floor window that the Irvings were hanging from...and that's where things went south.

Several firefighters quickly climbed the ladder, trying to reach the Irvings...too many of them, as it turned out, and the ladder fell (The NY Times article says it broke, I'm wondering of the bottom simply kicked out, but in either case...) the firefighters tumbled to the sidewalk, and the Irvings let out a collective groan of despair.

Thankfully the firefighters weren't injured, and quickly regrouped. They may have started to re-raise the ladder, but up on the third floor, John Irving came up with a new game plan...he first lowered his son, John Jr, then one of the boy's younger sisters down as far as he could reach, dropping them to the waiting firefighters who caught them and deposited them on the sidewalk...and then his wife screamed that two of the kids had run back to the bedroom and she couldn't get to them because of the smoke. Mr Irving told her to get out of the building, he'd go look for them. She refused, screaming that she wouldn't leave her kids even as her husband bodily dragged her to the window, and dropped her to the waiting firefighters as well, yelling down that he had to find his other two kids.

Ladder 8's guys were already raising another ladder, (Or re-raising the original one), yelling at him to get out of the building, that they'd go after them as they did so. I don't know for sure if Mr Irving jumped as well, or went down the ladder...The article says jumped, and I tend to agree, if for no other reason so he wouldn't delay the firefighters who quickly raised the ladder to the window. Two of them quickly scrambled up, and pulled themselves through the smoke-puking opening.

Keep in mind that this was long before any kind of breathing apparatus had even been thought of, so the best they could do was to stay low, crawling across the floor, breathing the tiny layer of breathable air next to the floor as they crawled to the first bedroom...the rooms were probably laid out 'railroad' style, one behind the other, with connecting doors, and the firefighters probably found the two kids cowering in that first room.

Did I mention it was getting hot in there as well, and that fire may have burned through the front door as they were carrying the kids back to the ladder? As they reached the window...the smoke was likely churning by now as fire rolled across the ceiling, and they only had a minute or so to make it out...the first firefighter to reach the window handed a child out to a comrade waiting on the ladder, that firefighter started down, carrying the terrified child. Then the firefighter at the window climbed out onto the ladder, took the second child, and started down, even as his partner bailed out onto the ladder right behind him. They likely hadn't reached the ground good when fire boiled out of the window they had just exited through. Ladder 8 had barely been on scene for ten minutes.

No more occupants would be rescued from the tenement, which was likely in 'Full Bloom' by now with fire rolling from every front window and through the roof. On top of that, the fire had extended across the roofs of all four tenements, flames were showing from the front windows of the third and fourth floors of 88 W 45th, and smoke was beginning to push from the eaves of the brick building at 92 W 45th, on the other side of the original fire building...things weren't lookin' good for the home team....

The scene was controlled bedlam as the Irving children were reunited with their parents...the rumbling crackle of flames overlaying the rocking clanking and shouted cadence of pumpers working, while several streams hissed into the fire, but it was obvious that the original fire building...and very likely 88 W 45th as well...were doomed. The crews pretty much 'X'ed off those two buildings and moved lines in place...front and rear,,,of 86 and 84 W 45th to try and stop it. They were about to get some much-needed help. Hose and Engine 46 (Possibly one of the very few 'two piece' companies in the city). made their way north on 7th Ave with the lighter hose wagon in the lead by a good half a block, their crews watching the ever-expanding orange glow.

They made the turn onto 45th and found the street lit up like noon-time, with flames rolling from just about every window of #90 as ladder 8 reunited the Irving children with their parents. The guys on the hose wagon wrapped a hydrant and laid the first of 46's lines in to the scene as the Steamer's crew made the turn, a cloud of smoke pushing from the rig's stack and following them up the street.

'How many lines can you guys pump??' A foreman asked Hose 46's crew as they spun a nozzle onto the end of the first line, getting a 'Two!!' in reply as a couple of the guys grabbed the female coupling on the end of the hose load, and started hand-jacking the second line back to the steamer...

At the hydrant, the crew nosed the engine in to plug, grabbed the suction hose, and made the connection (That front intake was way ahead of it's time BTW...modern pumpers have featured front intakes for decades because it makes 'hitting the plug' and connecting to the hydrant so much easier), spun the couplings of the two hand lines onto the pair of discharges just above and to the left of the intake, and waited for the call to 'Charge the lines!!'

When that call came minutes later, the steamer's engineer opened his throttle, then twisted the discharge valves open, and the lines jerked and swelled with water. The air became full of a new sound and sight that, would soon become common at fire scenes...the rapid, staccato 'CHF-CHF-CHF-CHF-CHF-CHF-CHF-' of a steam pumper running wide open as it punched a column of smoke skyward..