The Atlantic City Drawbridge Disaster

October 28, 1906

Atlantic City's Deadly Duo Part 2

When Jonathon Pitney invited several Philadelphia land developers to take a look at a remote, all but uninhabited 8-mile-long sand-spit just off of the New Jersey coast back in 1853, he kicked off something big. As in kicking off what would grow into a much-beloved major industry 'Big'. As in kicking off what would become a summer tradition for thousands upon thousands of families by planting the seeds that would grow into The Jersey Shore 'big'. As in kicking off the development of the nation's very first 'Railroad Resort'...a little burg we now call Atlantic City...'big'. That kind of big.

When trains started rolling along the Camden & Atlantic Railroad and Atlantic City opened for business, Pitney obviously hoped that the new city, as well as the railroad he built to serve it, would prosper. And thrive. And, most importantly, make Big Bucks for he and his backers.

And the soon to be Crown Jewel of The Jersey Shore did all of the above, succeeding beyond Dr. Pitney's wildest dreams. The public, though they didn't realize it until the first dozen or so trainloads of vacationers rolled into Atlantic City, wanted an easily accessible beach. I mean really wanted. Craved may even be a better word.

The first two hotels (The Beloe House, and the United States Hotel, the latter of which at one time was the largest hotel in the country) were soon joined by well over a dozen equally huge, even more lavish inns, while new attractions were added every summer. The city's soon to be legendary resort strip grew ever larger, expanding yearly, with new hotels and amusements, and restaurants, and other assorted attractions abuilding during the off-season to open, amid great fanfare and extravagant advertisements, at the beginning of each new summer season.

As the resort strip grew, so did the beach-craving crowds that flocked to it each summer. By 1878 500,000 people were riding the train into Atlantic City annually, and, by 1900, that total had more than doubled to well over a million visitors every summer, brought there by dozens of trains daily, rolling in on at least four different rail lines.

This led to a problem...Atlantic City was experiencing a traffic jam. The Camden and Atlantic had been joined by three other lines serving two different railroad stations, with nearly a hundred trains rolling into town daily during the summer. More trains were coming into the city than the infrastructure could really handle.

Not only were trains rolling into town right on top of each other, these same trains had to be turned around so they could head back out of the city. To do this, they probably used a turning wye...an arrangement of tracks and turnouts, shaped like, well, a 'y', that allowed trains to make what was essentially a three-point turn. This was not a quick, easy procedure, and in fact, it was manpower, time, and space intensive at best, and probably lead to iron-horse gridlock at worst.

Worst still, having that many train-movements in both that small of an area and that short of a period of time was just asking for a collision or three. There had, I'm sure, been minor incidents over the years, but not all of them were minor. The city fathers and railroad brass had already dealt with one major train wreck, and they really wanted to avoid another. The July 30, 1896 Atlantic City Diamond Crossing Collision was still fresh in their memories as the new century dawned, and they took great pains to avoid a repeat of that horror, or train collisions of any other variety, be they crossing collisions, rear end collisions, or head on collisions. All of the above could be equally devastating and deadly.

And they apparently did a pretty good job in avoiding another major collision, but they didn't foresee what would happen on Oct 28, 1906, and really, I'm not sure they could have. A decade and change after the Diamond Crossing collision took fifty lives, yet another train wreck matched that number and added to it, killing fifty-three. And that second wreck occurred partially because Atlantic City was modernizing its rail network. But that modernization had a tiny, but fatal, flaw and mechanical flaws can be every bit as deadly as carelessness ever dared to be.

Before we take a look at the wreck, we've got to take a quick look at the upgrades that were made to the 'West Jersey' as the locals called the West Jersey & Seashore. The Pennsylvania Railroad, which had become the owners of the West Jersey, was...as they tended to do in that era...going first class in a big way. And, unfortunately, those first-class upgrades ultimately led to the wreck.

In the decade between the two wrecks, Atlantic City grew all but exponentially. There were already at least three and possibly four separate rail lines coming in to the city by the beginning of the 20th Century, owned by the Reading Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad, the latter through a pair of lines run by Pennsy subsidiary West Jersey & Seashore RR., yet this still wasn't really enough to efficiently handle all of the rail traffic crossing The Thoroughfare every summer.

The Pennsylvania Railroad had purchased the original line into Atlantic City...the old Camden and Atlantic...back in 1896, merging it with the West Jersey, and giving that road two lines into the resort city. The Camden and Atlantic ran into hard times during it's latter years. Freight traffic yielded the highest revenues, and therefore profits, for railroads, and the Camden and Atlantic just didn't have that much freight traffic, unlike it's two chief rivals, the Reading and the Pennsylvania railroads, both of which were huge interstate rail systems.

The Camden and Atlantic was a 70 or so mile long point to point rail line that was originally built for one purpose...bringing vacationers to Atlantic City. There just wasn't that much business or industry to generate freight traffic. The C&A brass had to hope that heavy summer passenger traffic would yield enough profit to carry them through the other nine months of the year, and it, well, just didn't

So, through corporate manipulations that are far too complicated to even think delving into here, the old Camden and Atlantic became part of the huge Pennsylvania R.R. system, through the West Jersey & Seashore. And I have a feeling that the Pennsy/West Jersey suits found that the C&A infrastructure was, well, lacking. Still single tracked and aging, it really wasn't up to the heavy traffic that the summer beach season brought each year. Therefore, they set out to upgrade and modernize, and by upgrade, I mean seriously upgrade. In late 1906, The West Jersey introduced some truly revolutionary technology.

Back in 1888, just a dozen or so miles north of where I'm typing this, the very first electric street railroad, AKA trolley line, opened for business in Richmond Va. It was pretty much an instant success, and other cities, nationwide, quickly jumped on the band wagon. Again, I'm simplifying big time here, but railroads took notice, initially with thoughts of how to solve the problems of steam locomotives in long tunnels,

The first electric locomotive was developed in 1893, and in 1895, the Baltimore & Ohio opened the first electrified stretch of main line...a four mile long stretch of connector track that connected the City of Baltimore to the main line into New York. This line entered Baltimore through a series of long tunnels. After that connector line was electrified, the steam loco crews would bank their fires, then the electrics would couple on to them, and pull the trains through the tunnels, a system that was ultimately used in several other cities.

Seeing how effortlessly those first electric locomotives pulled entire trains, steam locomotives included, railroad brass began pondering on the question 'I wonder if electrifying long stretches of track and getting rid of the steam locomotive entirely would work?'. To make a long story short, yes...yes it would. Very very well, in fact.

The Pennsylvania Railroad got on the electrification bandwagon early, and probably included the West Jersey in those plans as soon as the option to pull their trains with electric locomotives became available. Oh...the Pennsy was going in a slightly different and arguably even more high tech direction with the West Jersey electrification.

Rather than an electric locomotive pulling a string of coaches, they decided to go with what were basically powered coaches...self-propelled, double-ended passenger cars, each with an operators compartment on both ends and their own self contained electric motor...a type that would become very familiar on subways, elevated trains, and commuter trains over the following decades, and that survives in more modern form to this very day.

The West Jersey bought sixty-eight of the new cars. Each of them was just over fifty-five feet long, weighed in at 89,000 lbs. apiece, and seated fifty-eight passengers. Most importantly, all of them...sixty-two 'chair cars', and six baggage-mail combinations...were motorized, with each of the cars powered by a pair of 200 H.P. General Electric electric motors...one on each truck, as the wheelsets are called. This meant that every car could be used as a 'control car' at the train's head end, and each train had a control car on both ends.

This gave the new cars a whole slew of advantages, not the least of which being they didn't have to be turned around in Atlantic City. On a multiple car train, all the engineer...actually known as a 'motorman' on an electric train...had to do was switch ends, now running the train from the operators compartment on the other end...now the front...of the train. Just pull out of the station, switch over onto the westbound track at a crossover, and head back for Camden.

Of course, if the West Jersey was going to upgrade it's rolling stock, they also needed to seriously upgrade their infrastructure as well. The first thing they did was double track the line, which would also double the number of trains that could run between Camden and Atlantic City in any given period of time.

Of course, double tracking the line also meant that they had to replace all of the bridges along that route as well, and electrifying that trackage just added an extra complication to that task. I have a feeling that one of the reasons that third rails were chosen for power transmission was because of the swing bridges that the line had to cross, all of which had to be rebuilt if not entirely replaced. It was probably far easier to connect/disconnect the third rail when the bridge was opened or closed than it would have been to do the same with an overhead trolley wire. (We're gonna look at this, as well as electrification of the line, a bit in 'NOTES' )

Speakin' of those swing bridges...One of the bridges that needed upgrading was the former Camden and Atlantic, now West Jersey, swing bridge over the Thoroughfare. Work on upgrading the former Camden and Atlantic track and bridges started in January of 1906 and continued through the first three-quarters of the year. Work probably progressed from west to east, and the bridge over The Thoroughfare was the last bridge to be upgraded. The Thoroughfare swing bridge didn't re-open to traffic until the new electric trains started running on September 18, 1906, likely amid much fanfare and after a huge amount of build-up. This also meant that the new bridge and the West Jersey's new electric trains both went in service too late for the Summer of '06' tourist season. It did, however, open in time to host Atlantic City's second major rail accident...

And this brings us to Sunday, October 28th, 1906.

The new bridge over The Thoroughfare, like it's predecessor, was a wooden trestle with an iron or steel swing-span at it's mid-point. The swing-span, also like it's predecessor, was powered by electricity...but there the similarities between the two bridges apparently ended. Being double tracked, the new bridge was wider than the one it replaced, which would have made the swing span larger and heavier as well. The new bridge also included installation of the third rails that provided power to the new electric trains' motors...lets take a quick look at the operation of this bridge.

When a ship or boat whistled for the bridge to be opened, the bridge tender referred to his train schedule, then replied, using the bridge whistle (Then as now, an air horn on electrically powered bridges) to advise the pilot and captain of the approaching vessel whether they were clear to proceed. Then he'd engage the bridge's electric motor and pull a 'johnson bar' like directional lever to open the bridge.

The mechanism that opened the bridge first lifted the entire lift span a few inches to disengage the third rail, then turned the bridge 90 degrees to open a pair of channels on either side of the swing span. The instant that bridge started turning, automatic signals...probably semaphores in that era...a half mile or so from either end of the bridge dropped to the 'STOP' position, the lights installed with them going red, indicating that the bridge was open and that approaching trains needed to stop short before reaching it..

Note the way I worded that...the signals didn't change until the bridge started swinging...not when the mechanism lifted it prior to turning it. Keep that in mind, it'll be real important a few paragraphs down, when we get into just what happened 116 years ago, at around 2:20 PM on October 28, 1906.

On that long ago Sunday afternoon. Atlantic City suffered a drawbridge accident...but it wouldn't be your typical drawbridge disaster...you know, the kind where an engineer ignores signals and manages to drive a train off of an open drawbridge. This one would come in out of left field, big-time, because when this drawbridge disaster happened, the bridge was closed.

Just how does a drawbridge disaster happen with the bridge closed???'. Remember that mechanical flaw I mentioned earlier...?'

Sometime around, or maybe a bit before 2 PM that afternoon, a yacht blew for the bridges over the thoroughfare to be opened (There were at least five of them back then...one for each rail line as well as a swing bridge for the Pleasantville-Atlantic City Turnpike. Getting all of them opened must've looked like a giant-sized water ballet of sorts.). In the bridge tender's cabin for the new West Jersey bridge, sixty-five year old Danial Stewart probably first glanced at his train schedule to make sure he wasn't getting ready to open the bridge beneath an oncoming train. When he saw that the next scheduled train wasn't due to pull out of the West Jersey's Atlantic City depot for about 20 minutes, he tooted the bridge's airhorn to let the yacht's pilot know he was clear to proceed, threw what was very likely an old fashioned knife-switch to start the process of opening the bridge, then yanked the 'johnson bar' to 'OPEN'.

As noted above, the bridge first raised about three inches or so, then started turning, powered by a big electric motor beneath the center of the swing-span. The instant the swing-span started turning, a pair of semaphores, a half mile or so from either end of the bridge, dropped to the horizontal position, indicating to on-coming engineers that they needed to stop short of the bridge. Upon seeing the 'STOP signal, most engineers would probably slow to a crawl, then stop where they could see the bridge, as well as a second pair of semaphores, hard by the span, that would indicate that the bridge was closed, locked, and safe to cross once the bridge was closed again.

But the semaphores went unseen this time. There were no trains approaching. One West Jersey train was getting ready to pull out of Atlantic City, and a second, inbound from Camden, was still about a half hour out. Dan Stewart probably just leaned out of one of the bridge tender cabin's windows, enjoying the crisp fall air as he watched the yacht ease through the channel between shore and swing-span, thoughts of his impending retirement passing through his head. He may have even wondered what it was like to be rich enough to afford a vessel such as the one passing the bridge, He didn't suspect for one second that he was less than a half hour away from witnessing a nightmare.

Then the yacht was clear, and Stewart shook his head, banishing the daydreams of retirement and large, expensive watercraft for the time being as he tooted the bridge's horn to warn that it would be moving, then pulled the Johnson Bar to 'CLOSE' and threw the knife switch again. Technology had evolved exponentially since the Norwalk Bridge Disaster fifty three years earlier. Bridge operation was now semi-automatic. The swing-span slowly turned back to the closed position, then as soon as the tracks were lined up horizontally, the electric motor powering it shut down and the span stopped turning. It was supposed to also lower as soon as the tracks on the swing span were lined up with those on the fixed section of the bridge, and it did... sort of. Somehow within the last few hours, the swing-span had been knocked out of balance. It lowered, but only one end actually lined up with the fixed track properly...the east end, closest to the Atlantic city rail terminal...and even that end wasn't perfectly lined up, as the rails on the bridge were tilted very subtly upwards.

Had the signaling system been designed to indicate that the bridge was completely lined up, both vertically and horizontally, the semaphores would have remained in the 'STOP' position, but the system only indicated horizontal alignment.

So as soon as swing-span stopped turning as it lined up with the tracks on the fixed trestle, the semaphores swung up to the vertical position, indicating that the bridge was closed, and the track was clear. Stewart then grasped the 'Johnson bar and shifted it back to the 'Locked' position...and as he did that, the semaphores hard by the ends of the bridge swung upwards, indicating...falsely...that the bridge was safe to cross.

As far as Stewart could tell, everything was perfectly normal. And as far as the signals were concerned, he was absolutely right.

Then, a few minutes after he closed the bridge, the 2:15 train from Atlantic City to Camden rumbled onto the bridge, eerily silent compared to steam locomotives, it's three cars looking for all the world as if they were rolling along without the benefit of a locomotive. The shoes sliding along the third rail may have spit the occasional blue spark, the wheels click-clacking over the rail joints, doing so particularly loudly as the train rolled across the joint between the fixed trestle and the swing-span itself.

And, as the train's motorman raised a hand in greeting as they passed the bridge tender's cabin, something completely unnoticed happened...the swing span tilted the other way. As the train crossed the out-of-balance span, its weight shifted from one end to the other, tilting the west end of the swing span downward, lining the track on that end of the swing span up with the fixed bridge just long enough for the train to safely cross from the swing span to the fixed section of the bridge.

Again, that distinctive 'click-clack' as the train's wheels crossed the gap between swing-span and trestle may have been a bit sharper than usual, the jolt felt by passengers and crew just a scosh rougher...but not enough for anyone to comment on it. If they did notice that extra-sharp little jolt, it was forgotten as the motorman moved the motor controller around its quadrant, and the train all but silently picked up speed...

**

..And, as the train accelerated westward across The Meadows, the out of balance swing span again tilted, kicking the west end upward and leaving the track on that end of the swing span about three or four inches higher than the track on the trestle. No one noticed the movement.

An hour or so before that westbound train crossed the swing-span, it's twin had pulled out of the new West Jersey terminal in Camden with motorman Walter Scott driving. Conductor John Curtis was in charge of the train, while Brakeman Ralph Wood rounded out the three man crew. Only two of the three would survive the trip.

About four miles east of the Camden terminal, Scott switched over from overhead wire to third rail, The train had two cars when it pulled out of Camden, running as a two car train until it rolled in to one of its first stops, Westville, bordering Camden to the south. The train had around 80 passengers distributed throughout its two coaches, most of them women and children. Twenty of the passengers were members of Tasca's Royal Artillery Band, enroute to Atlantic City to play at Young's Million Dollar Pier. A third coach was added in Westville, and several passengers moved to what was now the rear car of the train. Unfortunately for the band members, they elected to stay where they were.

The train made several more stops on the way to Atlantic City, dropping off and picking up passengers at each stop, until it reached The Meadows, just west of the bridge, sometime around 2:20 PM, rolling along at a good fifty or so. Walter Scott saw the westbound train approaching on the other track, and very likely raised his hand in greeting, maybe even giving the airhorn a quick blast as the two trains blurred past each other.

Shortly after they passed the westbound train, Scott spotted several semaphore signals...one set giving the status of the track ahead, another indicating whether the draw bridge over The Thoroughfare was open or closed...ahead of him. The arms of both were sticking straight up, the lights below the arms glowing green, indicating a clear track ahead.

Scott could see the new bridge about a half mile ahead of him. He had to start slowing both to enter Atlantic City, and to stop at the new Atlantic City terminal, less than a half mile beyond the bridge, so he backed the speed controller off a couple of notches, and possibly made a gentle application of the air brakes, slowing gradually to make the ride as gentle as possible for the train's passengers.

Early afternoon sunlight glinted off the thoroughfare as they approached the bridge, brakes hissing and squealing subtly, dragging the train's speed down to about 40 by the time they rolled onto the fixed trestle, seconds away from the swing-span. Below them, though they couldn't see it happening, water eddied and burbled around the bridge pilings as the tide rolled in.

Afternoon sun flickering off of the thoroughfare's placid water caught the attention of the train's passengers, and I can just about bet a mom or two pointed to the yacht receding in the distance and said 'See the boat?' to her child. Other passengers began making ready to disembark, a few others were carrying on conversation...and suddenly their world was shattered as the train's leading truck slammed into a cliff.

The 'cliff' was only three or four inches high, but it might as well have been a solid rock wall when the leading wheels hit it at forty miles per hour. The front end of the car bounced upward a good foot, jolting to the right at the same instant, then came down hard, with the front truck off the track and slued to the right. The hot-shoe broke contact with the third rail, killing power to the car instantly, but a combined hundred and thirty or so tons of momentum kept the train moving, shuddering along the ties and angling towards the edge of the swing-span as it went.

Every head in the car jerked around towards the sudden, solid, ringing 'BAM!!!' that reverberated from forward and beneath the car at the same instant that all of interior lights went out and all of them were thrown forward, catching themselves with a hand against the seat back ahead of them. A dozen moms threw the 'stiff-armed seatbelt' across their children's chests as the car started shuddering, bouncing rapidly up and down as it moved forward, still moving at between 35 and 40 MPH. and angling further to the right with every bounce.

In the control cabin at the forward end of the car, Scott caught himself before he was thrown headfirst through the car's tall, narrow windscreen, but he still likely slammed against the control pedestal painfully. Instinct and training kicked in, and, even as the shuddery bouncing blurred his view through the windscreen, he slammed the brakes into emergency, even though he knew it wouldn't do any good. He knew what was happening...the car had derailed, and the front truck was bouncing along the ties.

The first car's rear truck probably hit the end of the displaced swing-span at about the same instant Scott slammed the brakes into emergency, doing the same violent hop-and-skip as the front truck. The train's first car, now completely off the track, bounced along the ties, angling to the right, for maybe another 20 feet before plunging off of the south side of the swing-span. the falling car angled downward violently, still moving forward at thirty or so when it speared into the water fifteen feet below the tracks, sending a curtain-like geyser of water up and over the bridge.

The car's occupants screamed in terror as the front end of the car angled downward, then were pitched head long into aisles and over seat backs when the front end slammed into the water with about the same impact as slamming into a brick wall at 30 MPH, a wall of water bursting through the twin windscreens with the force of a dozen fire hoses, bowling people over like paper cups caught in a gutter during a downpour.

The car filled in an instant, going under like a crash-diving submarine, its front end slamming hard into the muddy bottom twenty or so feet below the surface. The car's front end dug into the bottom and kept going, angling away from the bridge, throwing mud-clouds aside as both its own momentum, multiplied by the momentum of the still coupled, still moving second and third coaches shoved it along the bottom.

The coupling between the first and second coaches likely ripped apart as they went off of the bridge, dropping the back end of the first coach straight down. A second curtain-shaped geyser of salt water blossomed up higher than the bridge deck as the back end of the lead car hit the water and just kept going, the rear truck sinking deep into the bottom mud.

The second coach didn't fare much better than the first, and its occupants got even less warning than those in the first coach. The front end of the car was suddenly jerked violently to the right and off the track, slamming across the up-kicked end of the swing-span at just about the same instant. Its wheels shuddered across the ties for about half the length of the swing-span before it, too, careened off of the bridge and sent a geyser skyward as it hit the water.

These coaches weren't meant to be water-tight and were immensely heavy. The second coach didn't even pretend to try to float, instead angling downward as water gushed in through dozens of openings while the panicked, terrified occupants desperately tried to pull themselves through open windows and open the doors at the ends of the car. The front end of the second coach probably slammed into the back end of the first as it went under, partially crushing the first car's roof, before ricocheting to the right and digging its own furrow through the bottom mud as it careened across the bottom of the thoroughfare.

Most of the passengers who were still in the first two coaches when they slammed into the water were probably thrown forward, ending up in a tangled mass of limbs at the forward ends of the cars. This violent tumble injured many of them as they bounced into seats, package shelves, and each other, making escape all but impossible. In the first coach, Motorman Walter Scott never even made it out of his operator's compartment, his body likely crushed by the mass of humanity that was slammed forward by the car's impact with the bottom.

Terrified watery bedlam reigned inside both coaches as passengers tried desperately to escape before the cars flooded and sank. They had only seconds...well less than a minute...to make their escape. I don't know if they broke windows out, or simply opened them, but a dozen or so passengers did make it out of windows, one of them being conductor John Curtiss. One man in the second coach, however, managed to get stuck as he was trying to pull himself through a window, and drowned as the car sank.

The third coach all but mimicked the second, jerking to the right and slamming across the end of the swing-span as the wheels jittered and bounced across the ties before hurtling off of the bridge and angling downward into the water, sending yet another curtain of water skyward...but the occupants of the third coach got a break. The passengers, and more importantly, brakeman Ralph Wood, had watched the two cars ahead of them plunge off of the bridge, and as the third coach's wheels jolted across the ties, Wood ran to the rear of the car and yanked hard on the lever that threw the doors open.

The passengers made for the doors almost as a single body, probably literally climbing over each other...and then the front end of the car tilted downward as it left the bridge. The women and children screamed, the men cursed...and the car slammed to a stop, throwing some of them forward. The coupling between the third and second cars, like that between the first and second, had torn loose, so the third coach was no longer being dragged along. Then, as the car fell from the bridge, either the coupling on the rear of the car, or possibly the rear truck itself got snagged on the abutment supporting the end of the swing-span, jerking the falling car to a sudden stop.

This break was only temporary...the car was tilted sharply downward, it's front end in the water and flooded back at least to the fifth or sixth row of seats. The car's own weight, as well as that of the water inside of it, was pulling it off of the abutment...the car's occupants could feel it shifting, hear the creaking and groaning as it started sliding.

"Come on-GO!!!" Wood yelled, and the passengers on the high end of the car started pulling themselves out of the door and onto the pilings, some of the men helping wives and children out as they escaped. Passengers further forward in the car frantically pulled themselves upward, using the tilted seat backs as a make-do ladder. As they reached the high end of the car, Wood boosted them out through the door.

Most of the escaping passengers made it up onto the bridge, a couple dropped into the water then swam to one of the pilings and held on to await rescue. In all about twenty people made it out of the car before the up-tilted end of the car finally yanked free and dropped straight down, slamming hard against the fixed trestle and tearing away about ten feet of its sidewall while it was at it. The front end of the car shoved a mini-tidal wave through the bridge pilings as it struck the water while the now-damaged rear end of the of the car slammed down hard on the wood-timbered abutment, bounced sideways, then kept sliding, tilting hard to the right as it slid, The car finally jerked to a stop with its damaged rear end resting partially on the abutment, canted to the right with several feet of its roof and damaged side out of the water. A couple more people managed to pull themselves out of wrecked car once it's mad fall stopped, Brakeman Wood among them.

Brakeman Wood rode the car down, then pulled himself out of the wildly tilted end door...or maybe even through the hole where the sidewall used to be....as the car filled, shot to the surface, and swam to safety. As I noted above, a couple more people escaped with him, but everyone hadn't made it out of the car...a couple of other heroes were made that day.

A passenger named Harry Roemer, who was likely on the low end of the tilted car, was pulling himself through an open window when the car slipped off of the pilings and sank. Roemer managed to pull himself free, shot to the surface and sucked in a lung-full of air, then went back down, swimming along the side of the car, kicking in several windows, and pulling several people from the third car before he had to go back up for air.

The wreck didn't go unseen...far from it, in fact. Atlantic City was a pretty bustling little burg, even in the off-season, and the Atlantic City end of that bridge was right smack in the middle of town, so dozens of people saw the wreck or its immediate aftermath. Bridge Tender Dan Stewart was the closest to the scene by far...he watched the eastbound train roll onto the bridge just as he'd done dozens of times before, watching it, but not really seeing it, daydreaming as his eyes followed the train, not really paying attention to it until the lead car suddenly jumped upward, hopped sideways, and plunged off of the bridge, the second and third cars following it over the side.

Stewart's eyes went huge as a curtain of white water rose upward, then collapsed, splashing onto the swing span...and suddenly the train was gone. What Stewart should have been doing was snatching up the telephone, ringing the operator, and calling in the cavalry...should have been doing. Instead, however, he bailed out of the cabin, and walked to his house, where he was found, in a state of shock, several hours later.

A work train was parked on a siding couple of hundred feet west of the bridge, and maintenance worker J.S. Deford just happened to be looking out of one of the windows in a crew-car (Bunk room), when the inbound electric train rumbled past. Like the bridge tender, Deford was possibly daydreaming as he watched the train rolled onto the bridge...then suddenly his thoughts were shattered when he watched it shift violently to the right and plunge off of the bridge. His reaction was the polar opposite of Stewart's...Deford bailed out of the bunk car and ran hard across the grassy, dusty expanse between the siding and the bridge.

He probably watched the third coach slide into the water just about the time he made it to the fixed trestle, and when he looked down into the water, he saw a nightmare, The first two cars were completely under, marked only by their trolley poles poking above the surface. One end of the third car, tilted crazily to the right, stuck out of the water hard by the wooden abutment supporting the swing-span's east end. Panicking, terrified people were swimming...or trying to swim in the heavy clothing of the era...in the water near the bridge.

The tide was coming in, and that helped some....at least they weren't being carried away from the bridge...but as it dragged the struggling passengers under the trestle, the water eddied and swirled around the pilings, making it difficult for them to hold on and stay above the surface...especially the kids.

Deford didn't hesitate more than the second or so that it took him to yank his shoes and jacket off before diving in....but it still wasn't that much he could do. He pulled three people onto the wooden abutment, but unfortunately, two were already dead. But at least he'd tried. And he wasn't the only one. One woman smashed her way through a window, shot to the surface and took a huge breath, then submarined back down, pulling a man through a window and taking him back up, where he swam to the abutment. She did this three more times, rescuing three more men, including her own husband, from one of the submerged cars.

Several men from town had seen the wreck and rushed to the bridge, diving in themselves...but by then the incoming tide was rushing hard and fast, putting them in as much danger as the people they were trying to rescue...more than the ones gathered on the abutment. Cooler heads, as they say, prevailed, and several boats were launched, a couple of them, by 1906, possibly even gasoline powered. If not gasoline, the workhorse of the era, steam.

Though there's no record of it happening, I can easily picture a big steam or gasoline launch nosing in to the abutment, her pilot holding her bow against the pilings with engine and rudder, deck crew probably first tying off with a quick-hitch secured bow line, then assisting the stranded train passengers on board as other crewmen pulled people still in the water out of harm's way.

A dozen or more boats were probably on scene with-in a half hour of the wreck, all competently and even expertly crewed, and they had their work cut out for them. Somewhere between thirty and forty people made it out of the three cars before they sank. While the larger launch's crew dealt with the people on the abutment, the crews of the smaller boats plucked people clinging to the trestle pilings out of the water.

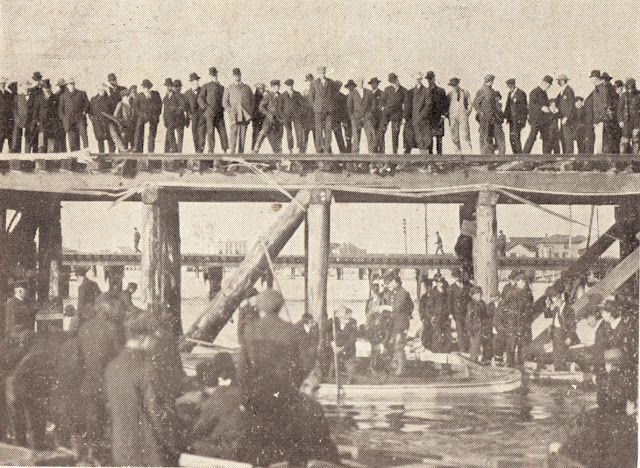

Unfortunately, not all of the citizens who flocked to the scene came to help. News of the accident spread through Atlantic City like wildfire, and hundreds if not thousands of people lined the bridge and the shorelines, many crossing the bridge over to The Meadows, watching the rescue and generally getting in the way.

Thankfully, several people had called both the cops and the fire department (What do you want to bet a few boxes were pulled, sending horse-drawn fire rigs rushing to the scene?) and several dozen officers ended up on scene, soon backed up by the Fire Department.

Police Chief Maxwell responded to the scene, and quickly had his men set up a cordon, at least pushing people back off of the bridge and on to the shore where they couldn't fall in and become even more of a problem. This singular task was more than enough to keep the Cops busy, but when a full first alarm assignment from the A.C.F.D. (Probably at least two engines, a truck company, and a battalion chief) rolled up, their guys really didn't have anything to do. Fire Chief Black arrived on scene fairly early in the incident (Then as now, major incidents attracted 'White Shirts' the way light attracts moths) and quickly made his guys available for 'Whatever was needed'. Several of them were temporarily detailed to Chief Maxwell, to assist with crowd control.

These guys had their work cut out for them in another, far more heartbreaking way...More than a few of the people watching the rescues were relatives of passengers who'd been on the train, waiting for word of their loved ones. And, as has happened at every major man-made disaster since it became possible to kill dozens of people at a time in one accident, those worried relatives crowd-rushed the cops and conscripted firefighters, demanding answers that were impossible to give. Sadly, this goes on at major incidents to this very day. Technology may have evolved hundreds of times in the last century and change, but worried-sick relatives terrified that their loved ones might be injured or worse have...and will...remain the same. Unfortunately, the relatives of fifty three of those passengers would have to wait until the morgue was opened to allow for public viewing the next morning. Hopefully, the relatives of the passengers who survived learned that their loved ones were still alive the evening of the accident.

Once things became a little organized, the phone lines began humming, and one of the first frantic phone calls made all but immediately after the wreck went to the West Jersey brass. The station master from Atlantic City was probably on scene almost before the rescues even began, and I can just about bet one of the West Jersey's new electric coaches was eastbound from Camden, scheduled as a special train, with the road's head honchos on board within a half hour or less of the wreck. They were likely on scene by 3:30 or so.

By that time anyone who survived the wreck was out of the water and the injured had been transported to the hospital. A few bodies...those that had somehow floated free of the submerged coaches...had been recovered and transported to a temporary morgue that had been set up at the nearby Empire Theater, but for the most part, things had reached an impasse, of sorts. The resources needed to recover bodies trapped in a submerged railroad car just didn't exist at the city...or even state...level in 1906. While the Navy, as well as civilian salvage firms, had and regularly used divers, their use in rescue and recovery situations such as this wreck was rare, and they were not set up for quick response. (A situation that's literally 180 degrees away from today. Now just about every coastal community as well as those with a large body of water within or bordering their boundaries either has their own fire department dive team or has access to one nearby that they can call for mutual aid. There would very likely be divers in the water within a half hour or less of any similar accident today.).

That's not saying that officials on scene just sat on their respective laurels and just waited for something to happen. Divers were quickly requested (Though I didn't see this stated, I believe they were U.S. Navy divers), while the West Jersey brass wasted no time in getting a pair of big wrecking cranes dispatched to the bridge. Again, though, this was 1906...none of this could happen particularly quickly.

The wrecking train was likely sitting on a side track, already made up and ready to roll...all they needed to do was couple a locomotive to it (A switch engine, already steamed up, was often used for this duty) and a crew had to be made up to man it (What do you want to bet this was handled with some form of on-call duty schedule?). The wreck train would have been ready to roll within an hour or less of being requested....but it likely didn't leave for a couple of hours.

The reason for this delay was likely the divers. If they were, in fact, U.S. Navy divers, they were probably dispatched from the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and it's a good bet that both divers and much of their equipment were brought to the scene by the same wreck train bringing the cranes...that would have been the most efficient way to transport them, at any rate...but it would have also delayed the wreck train's departure for the scene.

When they arrived in Atlantic City they still had to get a barge to work off of, and while that wouldn't have been a particularly difficult item to find in a coastal city, it still took time to find one, secure it's use, and get it to the scene. Enough time that, by the time our divers were on scene and on board the barge, gear and equipment sorted, checked, and ready to go, the sun was sliding down over The Meadows.

And one thing that they didn't have...and wouldn't have for more than a decade...was efficient and effective portable lights, and most importantly, a generator both portable enough and powerful enough to power them. All of the survivors had been rescued hours earlier by the time the divers were getting set up, and the operation had become purely a recovery operation. By a bit before Midnight, twenty-six bodies had been recovered and transported to the morgue, and the decision was made to hold off until the next morning.

While no activity took place after nightfall, I have a feeling that railroad and city officials burned a few barrels of midnight oil as planning sessions took place. So, once the sun came up the next morning, divers and crews returned to the scene and made ready to work (And the crowds returned and lined the banks of The Thoroughfare to watch the proceedings, likely again overtaxing the men of the A.C.P.D.)

While the city fathers and railroad brass burned midnight oil, relatives of missing passengers were showing up where-ever they thought they could get any information...the morgue, city Hall, the scene...and, to complicate matters even more, The Press was demanding information about the wreck itself. And The Pennsylvania Railroad, as Corporate America tended to do back then, absolutely and flatly refused to release any info.

The morning after the wreck, as operations at the scene ramped up, a public relations guru by the name of Ivy Lee, who is popularly regarded as the Father of Modern Public Relations, took a look at the incident and realized that The Pennsylvania R.R. (The parent company of The West Jersey & Seashore) had themselves a true public relations disaster brewing...brand new technology being involved in, or even worse, causing a major, catastrophic loss of life accident within the first month of beginning operation is still the stuff of corporate office nightmares.

The Pennsylvania Railroad Brass was refusing to release any info, which was tantamount, in the eyes of The Fourth Estate, to saying 'We Know We're Guilty'...trust me, Corporate America was seen as a dishonest and untrustworthy Evil by the Press, and much of the American public.

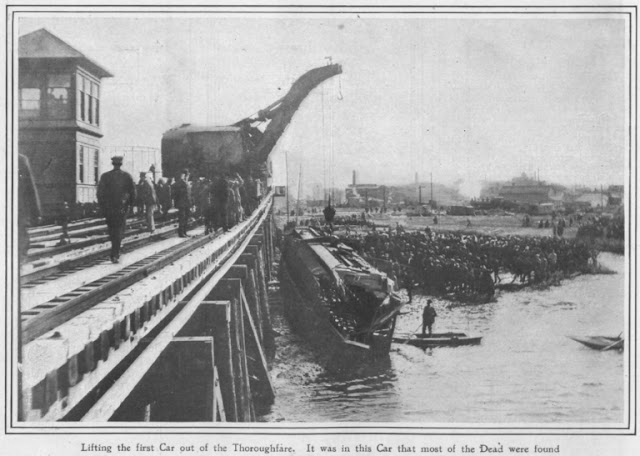

Lee got hold of the Pennsylvania R.R. brass, and persuaded them to not only release information and allow the Press on scene to take their own photos, he also persuaded them to give him the info and allow him to release it to major papers and wire services as what would go down in history as the very first press release. He also managed to get his ideas approved early enough in the operation for photos of the cars being lifted from the water to appear in papers along with the afore-mentioned premiere press release on October 30th, only two days after the wreck.

Of course, while Ivy Lee was meeting with the railroad brass-hats, divers and railroad employees and APD officers were gathering at the scene and setting up for what can only be described as a macabre day's work. I don't believe the divers entered the coaches to remove bodies, because I believe the decision was made to raise the cars, then remove the bodies...this would have been, by far, the easiest and most efficient way to recover the bodies of the deceased. The divers' main job was hooking the cables from the big steam cranes to the coaches. I would imagine they also made a sweep of the area in order to go ahead and recover any easily accessible bodies, and I believe several bodies were brought up and taken ashore aboard a big gas or steam powered launch before the cars were raised.

Once these tasks were complete, the big wreckers were eased out onto the bridge, and, one by one, the divers connected cables to the sunken cars so they could be worked in closer to the bridge, then raised and brought ashore. As each car was dragged ashore and secured, crews would enter the cars, and begin removing the bodies and loading them in ambulance wagons for transport to the temporary morgue.

***

Plenty of on-scene pics of this one. I didn't even try to pick and choose...I just posted all of the pics I found that were decent quality:

| Remember me commenting on how close spectators were allowed to be to the scene...here's the proof. Some of these guys had to have been railroad employees, though the boats may have been privately owned. I have a feeling this may have been earlier in the incident, before the wrecking train arrived on scene, while bodies that had floated free of the cars were being removed from the thoroughfare. The majority of the bodies were left aboard the submerged cars and removed once the cares were brought ashore. Take a look in the background, beyond the bridge, and you can see one of the other railroad bridges across the Thoroughfare...there were four of them by this time, as well as the bridge for the Pleasantville-Atlantic City Turnpike. All were in place and in use until at least the early to mid 1930s. |

And here's where a problem that seems to crop up at every incident with catastrophic loss of life from this era, and even well into the first quarter or so of the last century rears its head...no one's absolutely sure just how many people actually died. The most commonly quoted figure is 53, but a couple of sources have given the figure as 57, and one early newspaper article actually reported a death toll of 74, a figure that, thankfully, was greatly inflated.

Officials weren't even sure of just how many passengers were on the train in the first place, making it even more difficult to come up with a good figure for the total number of fatalities. They should have been able to compare the number of tickets sold to the number of survivors, and at least come up with a solid number of missing passengers. But it didn't work that way.

As I noted above, Conductor John Curtis survived the wreck, and was probably rescued, along with over a dozen passengers, from one of the bridge abutments. One of the very first things he was asked by his bosses after his rescue was how many passengers were on board. Should have been an easy question...all he had to do was count the tickets...but there was a problem.

After kicking his way through a window and nearly drowning, Curtis was all but totally traumatized...he couldn't even give them a cohesive account of what had happened and kept changing the total number of passengers to totals that were just shy of ridiculous.... all of the figures he gave them were north of one hundred...before finally admitting that he had no clue how many passengers were on board the train.

Ultimately eighty-eight punched, full fare tickets were found, and that was determined to be the total number of passengers on board. This figure apparently also matched up when officials compared the number of survivors to the number of fatalities, though when those two totals were added, they actually came up with 89. Only fifty-two of the fatalities were passengers...the fifty-third was Motorman Walter Scott. So they at least knew they didn't have anyone missing and had finally come up with the official number of fatalities.

All of the bodies were transported to the morgue, and a parade of distraught relatives of the missing shuffled through, desperately hoping their loved one wouldn't be under one of those shrouds even as they knew they would. Then a mother or wife would scream a horrible, despondent sob, or a husband or father would croak a more subdued, but still heart broken 'Oh, God', and another body would be officially I..D.ed.

There is very little more heartbreaking that having to identify a loved one's body, but a couple of these cases were especially heartrending. Philadelphia resident Fred Benckert, for example, was supposed to have made the trip to Atlantic City with his wife and two small sons, but some work obligation kept him from doing so, so he made the trip later. He traveled to Atlantic City by car, itself an adventure of the first magnitude in 1906, and arrived only to be told of the wreck. After searching for his family, he made his way to the morgue, only to find all three of them among the dead. Mr. Benckert is said to have fallen into a dead faint at the sight, and had to be helped from the building

Then there was Sam McElroy, also a Philly resident, who was making the trip to Atlantic City with his wife, five year old daughter, and three year old son. Apparently, he made it out of one of the cars, but was unable to rescue his family. After spending a sleepless night somewhere, he had to undergo the agony of watching the recovery operation the next day, then searching for his family at the morgue, and IDing the bodies of his wife and daughter. His son was still missing (And sadly, I found no info on whether the child was found or not, though I assume he was.). When asked for his home address as the inevitable forms were filled out, he gave the official his home address, but also informed him that he wouldn't be returning there, as there was nothing to return for.

These are just two of over fifty such sad tales.

As heartbreaking as this task was, identification of bodies was probably a fairly quick process, as almost all of the passengers were local, many of them actual residents of Atlantic City. Releasing the bodies to the families, and arranging transport to their funeral home of choice would have been yet another heartbreaking task, one that would have been a bit more time consuming as well as involving red tape and paperwork, but it, too, likely took only a couple of days at the most.

The funerals, however, probably seemed to go on forever.

A Coroner's Jury was all but inevitably convened to determine cause, and if possible, assign responsibility for the disaster, and once Pennsylvania Rail Road officials and mechanics discovered that the swing span was out of alignment and tilted, the cause was pretty straightforward. It was a mechanical glitch, nothing more or less, and for once, the Coroners Jury couldn't really assign blame for the accident. I can only assume that all the deaths were listed as being caused by drowning.

The three wrecked coaches sat, side by side, on the shore of the Thoroughfare until those same wreckers could put new trucks on the rails and lift the coaches onto them. (These were likely unpowered trucks used for the singular purpose pf towing the wrecks to the West Jersey shops...the original powered trucks were still on the bottom of the thoroughfare, and our divers likely assisted with their recovery as well.)

I can just about guarantee that the Pennsylvania railroad made sure that the cars were removed from the scene as quickly as possibly...they didn't want them sitting there in plain sight, reminding everyone who so much as glanced at them of the disaster, any longer than absolutely necessary. Then once they got them to the West Jersey shops, if at all possible, they were probably repaired and reused, if not as powered cars then as regular passenger coaches on another portion of the line. All three of the coaches were damaged in the tumble from the bridge, and from slamming into each other as they went in the water, but none of them appeared to be complete write-offs by any means.

It probably took another day or two for mechanics to chase down the gremlin that caused the problem and then fix it, but I can just about guarantee you that the bridge was repaired, back in service, with trains running again, within about a week.

All of the rail lines into Atlantic City, as well as the old turnpike, were still in use, with all of the drawbridges still in place, at least until the early-1930s (The last aerial photo I found with them in place was taken in 1933), but by 1957, only the present-day modern bridge (Today's NJT line, built on the old Reading RR right-of-way) was in place. The new Atlantic City Expressway had been added by 1970. The old right of ways...rail lines and old turnpike...were, and still apparently are, still clearly visible.

And the story pretty much fades away into the sunset. No memorial was ever erected to the memory of the fifty-three who died in The Thoroughfare that Long ago mid-fall Sunday afternoon. Even the bridge itself, and the rail line it served. is long gone, and the wreck has become a historic footnote in the city's history. At least it's somewhat remembered, unlike the diamond crossing collision a decade earlier. Unfortunately, like the fifty victims of that wreck, the Atlantic City Drawbridge Disaster's fifty-three victims remain without a memorial.

<***>NOTES, LINKS, AND STUFF<***>

I did not enjoy the same level of good luck, research-wise, with this post that I did with the Diamond Crossing collision's post. Not even close, in fact, and actually that's a little bit puzzling.

The Drawbridge Disaster is the best known of Atlantic City's two rail disasters, yet it's also the least represented of the two on the ol' inter-webs. Seriously, there was very little information out there about this one. This was especially puzzling considering that the very first press release...ever...was released by the Pennsylvania Railroad's embryotic public relations department with-in 24 hours of the wreck in an early effort at damage control.

The Drawbridge Disaster is also pretty well known among serious railfans, as well as serious scholars of Atlantic City history, so there should have been at least a little more info available, but, trust me on this, it just ain't out there...I looked.

Another interesting paradox is that the Drawbridge Disaster is by far the better represented of the two disasters in written, spoken, and video histories of the city despite the fact that it's the least represented on-line. Seriously, the Drawbridge Disaster is usually mentioned in some detail in any history of the resort city, while the Diamond Crossing collision is barely mentioned in passing, if at all.

Interesting Fact Number Three...this is the second time that a drawbridge disaster has overshadowed a diamond crossing collision in the media. (The first was when Chicago's Grand Crossing Collision was completely overshadowed by the Norwalk Bridge Disaster.). It seems a bit more puzzling in this case, though, because both incidents occurred in the same city, on the same rail line, were just about equally as deadly, and were both pretty spectacular, news-story wise.. I think the fact that the Drawbridge Disaster involved brand new, cutting edge technology, and happened right at the city's front door, in full view of many of it's citizens, may have had something to do with this.

The Drawbridge Disaster, BTW, was also one of the very early incidents of any kind to have fairly extensive photographic coverage in the press, some pretty good pics at that. I have a feeling that this fact alone may go a long way in explaining why the Drawbridge Disaster is the better known of the two...it became a press photographer's fantasy, one that they took full advantage of, making the Drawbridge Disaster, by far, the better documented of the two.

Speaking of those photos, happily, several of them are available on-line. Unfortunately, they included very little text describing just what you were looking at...not a problem with some shots, such as the cars being lifted from the water, but it would have been nice to know, for example, just where in the incident's timeline some of the more generic shots were taken. Still, it was nice to have some pics of the incident itself.

And as for links, I did manage to find one very good newspaper article that provided the bulk of my research, a slew of photos of the scene, and the Wiki page which, like the Diamond Crossing Disaster's Wiki page, was actually pretty sparse, info-wise.

Of course, there is a caveat to that newspaper article...news articles in that era were were both far more graphic than modern day news articles, as well as featuring near tabloid level sensationalism, so some of the actions reported may not have happened as written. Or even close to 'As Written'. Or, maybe even at all. One good example is that third coach....the article describes it as coming to rest almost completely submerged, while the photos clearly show that several feet of the car were out of the water, and that one end was heavily damaged, probably from hitting the bridge on the way down, a fact that was never even mentioned in the article.

How the wreck happened was pretty straightforward, of course, and that one detailed newspaper article I found gave a pretty good description of how the train went in the water, giving me a nice spring-board to use when describing the wreck as it happened. I, however, have no clue what really went on inside those three coaches in the minute or so between the first coach slamming into the out-of-sync swing span and the three coaches hitting the bottom of the Thoroughfare. It would be more than accurate and maybe even a bit of an understatement to call that minute or so a watery version of what nightmares are made of.

So...on to the 'Notes'!

<***>

Electrification was a huge technological advance for railroads in the late 19th/early 20th century and the West Jersey's parent company...the huge and legendary Pennsylvania Railroad System...adopted the new tech very early in the ball game. The P.R.R. used it extensively on portions of it's system, especially in the Northeast Corridor, until the road's ultimate twin demises...first being rolled into the Penn Central Transportation Company along with the New York Central and the New Haven railroads in 1969, then ultimately being gobbled up by Conrail and Amtrak in early 1976.

Electric locomotives were far more efficient than steam as well as far cleaner. But there was one drawback, initially, to electrification, and its name was infrastructure. When the Pennsylvania Railroad electrified one of its routes, they also had to build and install the infrastructure required to deliver the volts to the locomotives, and this resulted in a battle of the technologies that was even bigger than the infamous 'Betamax vs VHS' battle three quarters of a century later.

That battle was between Third Rail and Overhead Catenary systems, with the difference being that both systems won out in this case. As discussed in the main body of the post, a third rail is an electrically energized strip of metal that runs alongside the track to transmit electricity to a locomotive's motors through a 'hot shoe' attached to the locomotive or power car's trucks. This shoe slides along the rail to 'pick up' the electrical current. with the regular rails serving as the ground

On a train such as the West Jersey train involved in the wreck, each car is powered and has multiple shoes...generally one at each wheelset...and any one shoe can actually provide power for multiple cars.

This system is compact, comparatively inexpensive, and easy to build, but can be dangerous to the general public and railroad track maintenance workers. The rails carry both high amperage and somewhere around 600 volts, and coming into contact with the third rail would instantly fry anyone unfortunate enough do so.

Also, the rails have to be 'gapped' at grade crossings and the like...the third rail ends about 50 feet on either side of the grade crossing, and the train drifts through the gap, with the shoes resuming contact when the third rail continues. A buried cable bridges the gap between the two sections of third rail and the end of the third rail is ramped to ensure the reconnection with the shoe is smooth. Each car having multiple shoes helps out here, because if the train's long enough, there will always be a shoe in contact with the third rail on either side of the gap.

A similar buried cable also provides continuity at draw bridges, BTW. When the bridge is opened, the power is automatically switched to a cable, buried on the bottom of the body of water, that allows the circuit to remain complete. If this wasn't done, the circuit would be broken every time a bridge opened, stopping every train on that section of the line until the bridge closed again.

Then there were (And are) catenary systems, where a retractable framework on the roof of the locomotive picks up electricity from overhead wires suspended above the track. Far less dangerous to the public, but more difficult to build and maintain. The two systems battled it out at the beginning...

...And as I noted above, both systems won. The third rail system is still in heavy use in urban mass transit systems such as subways and Chicago's legendary 'El', while the catenary system is used on longer suburban lines, such as Metro North's line along Long Island Sound, as well as railroad mainlines such as Amtrak's operations along the Northeast Corridor.

Interestingly enough, though NJT has several electrified sections, their present-day line into Atlantic City isn't electrified. Those trains are headed by diesel locomotives.

<***>

The West Jersey's electrified line from Camden to Atlantic City generated more than a little controversy even before the Bridge Disaster occurred. There were several people killed or injured by the new electric trains in the month and a half between the line's opening and the disaster. At least three people were killed when struck by the trains, a couple more were injured in the same way, and there were also several close calls.

The lucky individuals who survived these far-too-close encounters with new technology all quoted the same causes for their accidents. They either didn't hear the train's near-silent approach, looked and saw only coaches and assumed they were not moving because they saw no locomotive, or a combination of the two.

While the argument can, and should, be made that if they had been both more careful and more observant, the accidents wouldn't have happened...walking across a railroad grade crossing without looking and listening has never been a good idea...their reasons actually had some merit.

These new motorized cars were very cutting edge for their day, and the idea of a railroad car moving under its own power, with no chuffing, steam and smoke belching behemoth at the head end of the train, was extremely difficult for John and Jane Q Public to get their collective heads around. People were used to watching for the column of smoke from the locomotive and listening for both the distinctive 'Chf-chf-chf-chf' of the locomotive's exhaust, and the sharp, shrill blast of a steam whistle.

The problem, of course, was the fact that there was no smoke column from the new cars, they were all but silent when approaching a crossing, and they had airhorns...likely among the first vehicles of any kind to be so equipped...rather than whistles. The airhorn's 'Bull in Heat' honk really didn't mean anything to the general public, though it should have made them at least look in the direction the sound was coming from to see what was making it.

Several people were also killed or injured when they came in contact with the third rail, but as the article I read noted, they pretty much had to be trespassing for this to happen. The third rails were well covered and guarded in the vicinity of stations and grade crossings, and there was a gap at the crossings themselves, as I noted above.

The accidents did instigate a call for better grade crossing safety (Watchmen at more crossings, and longer hours for the watchmen who were already in place. It'd be about a decade before the first automatic crossing signals...the venerable wig-wag signals...began appearing.).

<***>

Interestingly enough, several decades later, when diesel locomotives began heading up streamlined passenger trains, there was another rash of grade crossing accidents, these involving vehicles being struck by trains, and the absence of that tell-tale column of smoke was, once again, cited as one of the causes, along with drivers not recognizing the air horn as an oncoming train. I cover this as well as the iconic warning light that was developed to try and remedy the problem in the notes of this post .

<***>

Let's talk about our divers for a bit. Today, when we think of divers at an emergency scene such as the Bridge disaster, we think 'Scuba Diver', and picture our diver wearing a wet suit (Or dry suit...they look essentially identical, especially to the untrained observer.) and face mask, breathing through a regulator that's clenched between his teeth and connected to the single or double tank S.C.U.B.A. outfit on his back by hoses. This, of course, is exactly what modern day fire and police department scuba teams suit up in, and their units are often designated as 'Scuba Rescue' units.

And a problem raises it's head...in 1906, those familiar SCUBA outfits we're all so familiar hadn't been developed yet, and wouldn't be for nearly four decades. The first SCUBA gear of the type we're familiar with was developed during World War II by none other than the legendary Jacques Cousteau, and while self contained units such as oxygen rebreathers existed before before 1906, but weren't all that common nor were they cheap.

Generally commercial and military divers only had a couple of options.

They could use either the iconic diving helmets all of us are familiar with from watching cartoon deep sea divers do battle with cartoon octopi on Saturday mornings, or they could use early regulators and face masks. Regulators had been developed in the early 19th century, and one type, the Rouquayrol-Denayrouze was actually manufactured, with changes as technology progressed, from 1865 to 1965.

While some attempts at including a self contained air supply had been made, the means to store and supply high pressure gasses in such applications just wasn't there yet by 1906, nor would it be for a couple of decades or so, so all of these suits were supplied from an outside source...generally a ship or barge mounted air compressor. The earlier ones had been supplied by manually operated bellows.

My bet is our Navy divers utilized a full body diving suit with regulator and face mask for the recovery and salvage work in Atlantic City. The water depth was only about 20 feet, and they were working in close, cramped quarters, so the less cumbersome regulator and suit system would have been easier to work in, and probably safer, Of course, there was still one problem.

No matter which system they used, all of them were dragging an air hose along with them. This, of course, presented all kind of hazards. The hose could get snagged on the bridge or on wreckage and get cut, which would necessitate an immediate emergency ascent.

While that scenereo would've been sweaty-palm level scary, it wouldn't have been a death sentence by any means. These were, after all, professional divers, and they had probably drilled on the procedure for releasing their weight belts and shooting themselves to the surface to the point that they could do it in their sleep...it was, after all, a procedure that could potentially save their lives. If any of them did have to do an emergency surface, at least they weren't but twenty or so feet down, so the trip up to the surface...holding their breath, or more likely, breathing out slowly...wouldn't have taken but a few seconds, but it would have been a long, long few seconds!

Then there were the problems that weren't as dangerous, but were seriously aggravating, at best, such as getting the multiple air lines tangled when multiple divers were in the water. I believe a version of the 'Buddy System' was already policy for professional divers, be they military or commercial, so these guys probably went down in pairs. It wouldn't surprise me if, at least once or twice, a couple of divers had to back-trace their air hoses and untangle them before continuing.

These hoses, BTW, pretty much guaranteed that the divers wouldn't go inside the cars...had they done so, it wouldn't have been a case of If an air hose got snagged/cut/tangled, but When. And if one of the divers was inside one of the sunken coaches when he suffered a cut air hose, he wouldn't be able to surface quickly...or at all, and his name would have, sadly, very likely been added to the death toll from the wreck.

Of course...and I mentioned these devices above...there is the possibility our divers could have been equipped with something like the Fleuss Rebreather, which would have changed the whole ball game. These rigs reportedly allowed fairly decent bottom time and were self contained, so our divers wouldn't have had to drag an air hose around with them with all of the hazards and problems that entailed. These rigs would have also allowed far, far more freedom of movement, and if anyone had them it was likely to be the Navy, an organization known to do a bit of underwater work now and again. But even if the Navy did equip our divers with the rebreathers, they still didn't get in the water in time to do anything other than salvage and recovery. And they still wouldn't have gone inside the coaches to recover bodies, both because of visibility issues, and the cramped working conditions.

And most importantly, and sadly, there absolutely wouldn't have been any live rescues. While it's nice to think of our divers hustling to get in the water, and possibly make some rescues, it just wouldn't have happened...Time was against them from the instant a telephone rang at the Philly Navy Yard.

Anyone who didn't escape from the cars died within a couple of minutes of them going in the water, while it would have taken the divers, at best, two or so hours to get on scene, and that's if everything went absolutely smoothly from the minute a grizzled Chief answered our phone call. Once they got on scene, even if they were using the rebreathers, which would have cut their dress-out time immensely, it would have still very likely been 5 PM or so before a diver went in the water. (Full disclosure here, gang...one source did report that divers were in the water with-in an hour after the wreck, but I could find no details as to how they pulled that off, especially if our divers were Navy divers, coming from Philadelphia. Today they could absolutely have divers in the water well within an hour. Heck, with-in a half hour, and they'd be A.C.F.D. divers . But in1906? Can't see it happening.).

Their first task upon getting in the water would have been recon...determining just how the cars were resting on the bottom and how difficult either recovering the bodies or the cars themselves would be, as well as recovering any bodies that were immediately accessible. The decision to raise the cars and then recover the bodies was likely made very early in the ball game, possibly even before the first diver went in the water.

This type of dive is never a walk in the park, but this one was particularly hard on these guys. I read a description of what one of the first divers in the water saw when he looked in one of the coaches...the very first thing that met his eyes was a young child pressed up against a window. That, guys, is what PTSD, which wouldn't actually be identified and defined for nearly three quarters of a century, is made of.

Then, as described in the main body of the post, they assisted with rigging the cars to be raised. Our divers, guys, performed salvage and recon.

<***>

Emergency response to the Drawbridge Disaster wasn't quite 180 degrees away from what a modern response to a similar incident would be today...150 degrees maybe, but not a full 180.

There was actually a fairly effective emergency response, with multiple rescues made fairly early in the incident, and everyone who made it out of the coaches was on dry land with-in about an hour of the wreck. The only thing was, most, in not all, of these rescues were made by citizens and railroad employees rather then the fire department.

Back in this era, fire departments were set up to do one thing really well...operate at fires. The first purpose-organized rescue unit...FDNY's legendary Rescue 1...wouldn't go in service until 1915, and, while big-city departments located on the coast, or on the Great Lakes, had fireboats which were used to rescue people in the water occasionally, even these companies were mainly set up for, well, water-borne fire-fighting.

Smaller cities such as Atlantic City often didn't have fireboats, and Atlantic City's fire department...which had just gone fully paid two years earlier...had absolutely no water rescue capability in 1906. While the department did respond to the drawbridge disaster, likely to a pulled box or two, when they got to the scene there really wasn't much they could do. Citizens with boats had the rescues well under way, there was no fire, and they had absolutely no capability to deal with the submerged cars. When AFD's Chief of Department arrived on scene, very likely after being advised of what they had by the Alarm Office, he detailed his guys to assist the Police Department with crowd control.

Once the Navy divers arrived on scene, A.C.F.D.'s guys were likely released from the scene, and returned to service.

As for the cops, their task on scene was actually very similar to what the modern APD would be doing on a similar scene...crowd control and perimeter control, and from what I read, they had their work cut out for them (And from the pictures of the recovery operation, they ultimately got overwhelmed by the huge crowd)

The railroad, assisted by Navy divers, apparently handled the heavy work, while the police department likely handled body recovery once the cars were pulled up on shore, possibly assisted by the Fire Department. But the Atlantic City Fire Department played, at best, a secondary role in the incident.

NOW...lets take a quick look at the likely response if, say, the all but improbable happened and a NJT train managed to run an open swing bridge. To make it interesting, lets have the tones hit at either morning or evening rush hour.

The dispatcher lists off a long list of units to respond, then announces 'At the NJT bridge, for a train in the water...'

'Oh S--T!...would be spoken...loudly...a couple of times as the guys and gals slid the poles and bailed into the apparatus bays, trust me on this. Battery trickle-charger cords would be yanked free, turnouts would be pulled on, crew compartment doors would 'Crump!' closed as bay doors rumbled up, and big diesel engines would crank over with the sound of multiple giants clearing their throats. At Fire Station 2, a pair of boat trailers, each mounting a Zodiac, would be hitched up, one to Rescue 1's rig, the other likely to Special Ops 1's big dualie pick-up. Rigs would then pull out of the stations, swinging towards The Thoroughfare, Federal 'Q sirens yowling and air horns braying.

AT AFD's Fire Headquarters, the white-shirts would head for their cars, AFD Chief of Department Scott Evans among them. Atlantic City's FD would respond big, with Engine 2 responding from their North Indiana Ave station, only a half mile or so from the scene, first due. Engine 2 would be followed closely by Rescue 1 and Special Ops 1, each towing a Zodiac. The Zodiacs would be in the water with-in minutes of the tones hitting, their crews searching for any passengers or train crew who are in the water.

Atlantic City's Dive Team would be responding from Station 1, with divers paged out and converging on the scene from their duty stations...several would probably be with companies already responding to the scene.. They'd be putting divers in the water with-in 15 minutes of the train going in the water.

On shore, a command post would have been set up by the first due Battalion Chief, and a major incident would be declared, It's a good bet that Chief Evans would take command when he arrived. The Batt Chief would quickly give him a progress report, telling him what had already been done, and what resources he'd already requested, then he'd turn command over to Chief Evans, who would start divvying the scene into sectors (Marine, Medical, Rescue, etc) and giving each sector to one of his deputy or Battalion Chiefs. Dispatch would have already assigned a radio channel to the incident, and each major sector would very possibly get it's own channel.

It being a navigable waterway, I have a feeling the Coast Guard would be on scene to assist in short order as well.