The Atlantic City Diamond Crossing Train Collision

July 30, 1896

Atlantic City's Deadly Duo Part 1

A Deadly End To A Day At The Beach

By the time 1896 rolled around, there were just shy of 190,000 miles of revenue generating railroad in the U.S., an increase of right around 2000% over the total mileage forty-three years earlier, in 1853, the year that Chicago's Grand Crossing Disaster...the nation's first major loss of life train wreck and subject of my last post...occurred. That averages out to about 4200 miles of new track per year, every year, for four decades and change...someone had definitely been busy 'Workin' On The Railroad', as the classic old tune goes.

While those 190,000 miles were a bit more evenly distributed across the nation in 1896 than they were four decades earlier, the Northeast still boasted well more than its share of track. Just take a look at the number of major cities stuffed into the 440 or so mile stretch between Washington, DC and Boston, Mass. and you begin to understand why. Simply put there were (And are) a slew of people stuffed into that relatively small area.

Rail lines were built where the people were, and by the late 19th Century, the Northeastern U.S was already pretty well packed with said people, with more arriving every day. On top of that, the region was home to much of the nation's heavy industry as well as several of the country's largest and busiest ports (Including the busiest, a little burg named New York City). Thanks to the ever-growing transportation needs of what's known today as the Northeast Corridor, track milage in the region increased even more quickly than it did in the rest of the country.

By 1896 there were probably 30,000 miles or more of track in the northeast alone, and when you have that many rail lines in that small of an area, it's a given that they are going to cross each other a bit more than occasionally.

Ideally, all of these crossings would have been what the railroads refer to as 'Grade Separated'...one line crossing the other on a bridge...from the git-go. This is obviously the safest way to go, but needless to say, not the least expensive...just the opposite in fact. And the railroad bean counters...like those in any and all industries... absolutely hated 'expensive', so if they were given the choice between Expensive and Safe vs Inexpensive and Not So Safe, inexpensive would win every time.

This is why there were way more than a few locations where railroads crossed each other at grade, the tracks crossing at what's called a 'Diamond Crossing'. Frogs, as the slotted metal castings that allow two tracks to intersect are called, are way less expensive than bridges. Of course, once those crossings were in place you had the minor little issue of two trains approaching the same crossing at the same time, often several times a day on busy rail lines.

This, needless to say, invited disaster on engraved invitations, and my post about the Grand Crossing Collision illustrated that just about perfectly. Sure, safety technology had advanced in leaps and bounds in the forty-three years between 1853 and1896, and that should have prevented, or at least minimized such disasters. The tools to do so were certainly in place as the end of the 19th Century loomed.

All of the major railroads had installed air brakes on their trains, covered vestibules between passenger cars were becoming more common, passenger cars were heated by steam rather than stoves in each car, and most passenger trains had electric lighting rather than oil or kerosene lamps. On the track side of things, by the end of the 19th Century block signaling was replacing timetable based traffic control, which meant that the great majority of diamond crossings were also protected by trackside signals. Granted, they were often manual rather than automatic, but that was still far better than no signals. Well, most of the time, anyway.

See, there's a reason I mentioned these manual signals...one thing that all of the more-modern technology in the world can't change is human nature. And manual signals were controlled by, well, humans. And humans have an unfortunate tendency to make mistakes. And those manual signals, coupled with a couple of those mistakes, were very much the cause when, forty-three years and change after the Grand Crossing Collision, there was yet another diamond crossing collision, and this one was about three times more deadly.

For this one we're heading for the Jersey Shore, and specifically, to Atlantic City, New Jersey. You know Atlantic City...featured most famously in the beloved board game 'Monopoly', most recently in the hit HBO series 'Boardwalk Empire', and currently, while still beloved for its beaches and boardwalk, probably best known as the second most popular gambling destination in the U.S.

In the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries, Atlantic City was known for its beaches, huge, lavish and luxurious hotels, and seven-mile-long boardwalk. What a lot of people don't know about Atlantic City, however, is that it was one of the very first 'Railroad Resorts'. It was, in fact, very literally built to be a railroad resort.

*

|

| An Atlantic City beach scene from mid-summer 1896...crowds at the beach are not a new thing! |

*

In the early 1850s, a New Jersey doctor named Jonathon Pitney got hold of a group of developers from Philadelphia and invited them to come and take a look at some land. The land in question was a large, isolated sandspit off of the New Jersey coast...an eight-mile-long arrowhead shaped expanse of sand and dunes and grasses that, while picturesque, didn't seem to be all that useful. It wasn't easily accessible, had few structures and no roads, and boasted a total population of about eight.

Nonetheless, the good Doctor and these future-gazing developers looked over said sand-spit, rubbed their chins thoughtfully, and surmised 'If we build a big hotel here, connect it to Philadelphia via a rail line, and advertise the benefits of a beach vacation during the broiling hot summer months, They Will Come...

So, Atlantic City was laid out on the wider, northern end of the sandspit, streets were graded, construction was started on the Belloe House and the United States Hotels as well as the Camden and Atlantic Railroad, stretching from Camden N.J. to the new beach city, and when all of the above were completed and advertised, 'they' did indeed come. Okay, the development of Atlantic City may have been a little more complicated than that, but those developers who gazed across that sandspit and saw dollar signs hit it right on the money.

Both the United States Hotel and the Belloe House were owned by the Camden and Atlantic, so the railroad (And its owners) made a handsome profit off of every facet of Atlantic City's early years, and still turned a handsome profit when other hotels were built shoulder to shoulder along Atlantic Ave.

The Camden & Atlantic RR, and Atlantic City itself, just about had a monopoly at the time...see, going to the beach was way more complicated in the mid 19th Century than it is now (And has been for nearly a century.). Today, you want to go to the beach, you load kids and dogs and beach toys and such into the Family Truckster, maybe hook a boat or personal watercraft to the trailer hitch, jump on one of those roads with a red, white, and blue shield denoting the route number, and head for your beach of choice.

If you live in one of the coastal states along the US. East Coast, you're no more than five hours from a beach, and that's if you live, say, in the westernmost reaches of Virginia or North Carolina. Most people on the East Coast live three hours or less from several beaches. It can literally be a day trip. Leave home by 7:30AM, be at the beach well before lunchtime, spend a good six or more hours on the beach (Long enough for a real good burn!), leave around supper-time, and be home in time for the eleven o'clock news..

Even if your home's in one of the land locked states, if you want to spend a week at the beach it's still only a two or three day trip at the most by car or a flight of a few hours on one of those big birds built by Boeing or Airbus.

In 1853, however, there just weren't many real resort beaches (If there were any). Unless the beach was hard by a major city, it wasn't easily accessible, and if you wanted to stay there for a few days, you'd be living in a tent. And there was no way to get to the beach quickly, unless you lived practically within sight of it.

Atlantic City changed that. Jump on one of the Camden & Atlantic's trains in Camden, N.J, just across the Delaware River from Philly, or at one of the towns between Philadelphia and Atlantic City served by the line, sit back in an upholstered seat in a railroad passenger coach, watch the scenery roll by, and be among the first several thousand people to experience that lovely feeling of 'Being Able To Smell The Ocean' when you're a few miles from the beach.

Then you had the hotels, which were massive and luxurious and overlooked miles upon miles of pristine beach with the Atlantic surf smacking the sand. Attractions were added yearly. The boardwalk was added around 1870 and expanded annually. Specialty shops and restaurants were opened, side shows and amusement parks were added, and the beach got more crowded every year.

By 1874, even though the city's permanent population was only around 2500, the summer population exploded every year, with around 500,000 people riding the train into Atlantic City annually to spend a few weeks frolicking in the sun. By 1896, the year we're looking at in this post, the number of visitors had grown exponentially, and the number of railroads serving the Crown Jewel of the embryotic Jersey Shore had, at the very least, quadrupled, with the Camden & Atlantic, the West Jersey and Seashore, the Reading Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad all running trains into the city.

This extensive rail network had made Atlantic City into a popular summer day-trip destination for groups, associations, and lodges. Members of these various organizations and their families would board an excursion train early in the morning for the hour or two trip to Atlantic City, be on the beach well before noon, spend a long day in the sun and surf, and catch another train home that evening.

One group that booked such an excursion was the Bridgeton Chapter of the of the Improved Order Of Red Men from Bridgeton, New Jersey, forty or so miles southwest of Atlantic City, in the southwestern part of the state. They booked the trip for Saturday, July 30th, and gathered at the Bridgeton train station probably around 8AM or so, to board and make the hour or so trip to Atlantic City.

I'll let your imaginations play with that happy scene. Dozens of giddily excited kids on that adrenalin-and-sugar fueled high that beach-bound kids have down to an art form, while their parents tried, with that chaotic desperation known to parents the world over, to keep their flocks of kids and their gear more or less organized. Keep in mind here that families tended to be large back then.

Ultimately rounding up said kids...threats of 'Turning Around And Going Right Back Home', a standard weapon in the parental arsenal for centuries, were very likely deployed here and there...before getting ready to board. Brightly colored miniature metal pails and equally colorful metal shovels, along with whatever other toys and gear accompanied families to the beach in the late 19th Century were in abundant supply, as were bags holding extra clothing and swimwear for kids and parents alike. The air was absolutely tingling with excitement.

Finally getting aboard (There were reportedly as many as five or six hundred people on this excursion), and the train was alive with that giddy, giggly kid feeling, mirrored a bit more conservatively by their parents, as the locomotive started chugging busily, the train jerking gently as it started moving. To understand the excitement level on that train, you have to remember, this type of trip was a, maybe, once in a summer event for inland-dwellers back then. You couldn't just jump in your car, get on the interstate, and head for the beach for the day every other weekend or so.

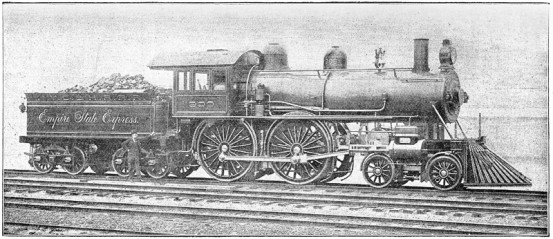

The excursion train they had just boarded was operated by the West Jersey and Sea Shore Railroad, one of the newer lines serving Atlantic City. The nearly 600 beach-goers were distributed through seven wooden coaches, very possibly headed up by a more modern version of the famed 4-4-0 American class, or maybe a 'Ten Wheeler' (4-6-0) or another larger class of passenger locomotive, with engineer John Greiner at the throttle.

*

They had probably arrived in Atlantic City by 10AM, and, while the excursionists were enjoying the beach, the train crew would enjoy a little down time...but not much. They had to service the locomotive with coal and water, oil the moving parts, inspect the brakes and other safety gear, and generally make sure the train was ready to head back west. Train orders had to be received from the dispatcher, then the train was likely run out to a turning wye to get swung around so the locomotive was aimed in the right direction for the trip home, that itself a laborious and manpower-intensive process.

By 6 PM the locomotive had been serviced, the train turned, and the crew fed. Also, by 6 PM, after eight or so hours on the beach, those same kids and parents were pleasantly bushed, ready to head for home, and gathering at Atlantic City's rail terminal, ready to board the train for the return trip. The boarding process took maybe a bit longer than normal, but by 6:40 PM all of them had grabbed seats throughout those seven coaches. Parents were talking about the day, laughing at humorous happenings, and comparing their and their kids' activities. The younger kids were quietly examining seashells and other gathered treasures, some of them leaning against their parents and each other in that sun-induced stupor all of us remember pleasantly from our childhoods. Meanwhile, the teens in the group talked among themselves, comparing and contrasting experiences, boys discussing hot girls and girls cute guys spotted, giggles inevitably erupting from the latter as the train pulled out of the station, about 10 minutes late, and headed west through the center of Atlantic City. In theory they were maybe an hour or so from Bridgeton. They wouldn't make it.

At the time, the WJ & SS...referred to from here on as the 'West Jersey'... tracks paralleled both the original rail line into Atlantic City...the Camden and Atlantic Railroad, by then actually a subsidiary of the West Jersey...and a competitor, the former Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railroad, now owned by the huge Reading Railroad system. From what I could gather, The Camden & Atlantic tracks ran just to the north of the West Jersey's tracks, the Reading tracks just to the south. The West Jersey tracks arrowed southwest for about three miles before they had to swing slightly northward to follow the northern shore of Lakes Bay before once again turning towards Bridgeton.

The Reading tracks also slanted southwest for a shade over two miles before, a bit more than a mile from the drawbridges over the narrow channel known as The Thoroughfare, curving gently northward to aim towards Philadelphia. Less than a hundred feet past that curve, they crossed the West Jersey tracks on a diamond crossing at an extreme angle.

This was a dangerous crossing, especially during the summer when traffic was heavy, and the extreme angle probably didn't help at all. Forward visibility from either side of a steam locomotive's cab is poor already without the added handicap of a screwed-up sight line thrown into the mix. On top of that is the fact that by the time an engineer realized that another train was fouling the crossing, it would be far too late to bring his train to a stop, even with modern airbrakes. There had to be a way to control traffic to avoid...well to avoid incidents like the one I'm covering in this post. And there was, in fact, traffic control in place, traffic control that had worked flawlessly for at least a couple of decades.

Hard by the crossing was what is known in railroad parlance as a 'Tower'...a small two-story structure with the entire upper half of all four second story walls consisting of windows. The tower operator's primary responsibility was controlling traffic passing through the crossing. To do this he set manually controlled semaphore signals that indicated whether the crossing was clear or occupied, and if a train...or pair of trains...was approaching it, which of them had the right of way.

Railroad semaphore signals consisted of a brightly painted wooden or metal arm, mounted on a pivot at the top of a tall mast beside the tracks. If this arm was vertical, it indicated the track ahead was clear, set diagonally, meant that the engineer needed to be prepared to stop at the next signal, and horizontal indicated 'STOP until the signal indicated otherwise.

The Reading's double-tracks had three semaphores on either side of the crossing, the furthest out about 2000 yards...just over a mile...west of the crossing. The West Jerseys' tracks east of the crossing were controlled by a pair of semaphores, the furthest out very likely just west of the drawbridge. These signals were what were known as interlocking signals...if the operator set the signal to indicate, say 'Clear' for the West Jersy, the signals for the Reading would automatically set to 'STOP', and vice versa.

The signals weren't set on a whim of the operator, either...or at least they weren't supposed to be. There was a hierarchy of trains and a protocol that was to be followed. Inbound trains had priority over outbound trains. And top priority trains, such as express trains, had priority over lower priority trains, such as our excursion train, which was considered an 'Extra' train. On top of that, scheduled trains always had the right of way over 'extra' trains.

*

*

About fifty minutes before the West Jersey excursion train pulled out of Atlantic City's terminal, an express train, bound for Atlantic City, pulled out of Philadelphia's Reading Terminal and headed east, with veteran engineer Edward Farr in the locomotive's right seat. The train was cleared through to Atlantic City with few stops, so Farr shoved the throttle open once they cleared the station and rolled onto the branch line from Philly to A.C, and by the time they crossed the Delaware River on the newly built Delair Bridge, they were rocking along at between 50 and 60 mph. In Atlantic City, the tired excursionists were gathering kids and belongings to make their way to the West Jersey railroad station. Fifty people had right around an hour to live.

Back in Atlantic City, not quite an hour after the Express pulled out of Philly's old Reading Station, Greiner was pulling out of Atlantic City's West Jersey/Camden and Atlantic train depot. He had to keep the excursion train's speed down until he crossed a drawbridge over the Thoroughfare...a winding channel separating Atlantic City from the mainland...but once he crossed the bridge, he, too, could shove the throttle open...but not wide open. Just under a mile after crossing the drawbridge, he had to cross the Reading tracks, and he needed to watch for the semaphore near the bridge...the 'distant' signal. If it was yellow...which he seriously suspected it would be because he knew the express was due just before 7PM...it would mean he should be ready to stop at the second signal...the 'Home' signal, nearer the crossing.

On that Saturday evening, a fellow by the name of George Hauser was manning the tower. The Reading/West Jersey crossing was situated on a marshy, wooded peninsula in a compact little region of N.J. known as The Meadows, and the tower was probably sited in the crossing's northern quadrant, situated so the tower operator could see for a couple of miles, both east and west, along both sets of tracks. Most importantly, he could see up the West Jersey tracks, all the way to the drawbridge.

On that hot July evening, Hauser not only had this unobstructed view of the rail lines to guide his actions, it's a pretty good bet that he also had a copy of the train schedules as well as a clipboard holding any special train orders to guide him, On top of that, he was probably well aware that the daily 5:40 Reading R.R. express from Philly, scheduled to arrive in Atlantic City at 6:55 PM, was due.

In fact, as the minute hand of the big clock set on the tower's wall eased upward across the '9', and the hour hand crept ever closer to '7', he was probably looking at the Reading express, still a couple of miles out. He then turned to look up the West Jersey tracks. Thanks to the train order board, he also knew that an 'Extra' train, an excursion train bound for Bridgeton, was due to pass the tower any minute. In fact, as he turned and looked back towards Atlantic City, he could also see the excursion crossing the drawbridge.

As I noted above, there were explicit rules and regulations that dealt with this very situation. The express train was inbound and a regularly scheduled train at that. The excursion train was outbound, and a lower priority 'extra' train. So it should have been a simple, and all but instinctive move...the Reading express train should have been given the right of way, and the two semaphores for the excursion train should have been set, respectively, to' Caution' and 'STOP'...but that's not the way it happened.

The Express was between one and two miles out. The Excursion was less than a mile out. Hauser did some quick mental triangulation, squinted meaningfully, then grabbed one of the shoulder-high metal levers that controlled the semaphores, and heaved on it, pulling it towards him. Inexplicably, the semaphores for the West Jersey...the excursion train...swung upright, indicating a clear track. At the same time, the signals controlling the Reading dropped, the distant and midpoint signals going to a diagonal position to indicate 'Prepare To Stop, the 'Home' signal...closest to the crossing...dropping until it was horizontal, indicating 'STOP'.

As the excursion train rolled off the drawbridge, Greiner was leaning out of the cab's right side picture window, peering ahead of the locomotive, rolling along at about 25 MPH or so as he looked for the signal mast that should be visible on the right side of the right-of-way. While Greiner could see the right side of the tracks, he couldn't see to the locomotive's left, because the boiler blocked his view, which also meant he couldn't see the Reading's tracks east of the crossing...but he could see them, angling away, ahead and to his right, west of the crossing, so it's a good bet he could at least see the smoke from the express train's locomotive. In fact, it's not at all unlikely he was actually expecting to see the express train as it was a daily run.

This should have been his first clue that he was going to have to stop. He should have backed off of the throttle and pulled the train's airbrakes into the 'service' position, slowing the train to bring it to a smooth, slow stop short of the crossing, because he, like the tower operator, was more than familiar with the regulations governing the crossing. Inbound trains had the right of way.

But there was a problem...about the time he spotted the express train, likely saying something like 'Reading express's inbound...he's a little early...', Greiner also saw the 'Distant' semaphore signal, and the long, red and white finger of the semaphore was vertical, indicating that his train had the right of way, and a clear track. Greiner pulled the throttle towards him, at the same time looking over towards his fireman and saying '...Annnd, believe it or not, we've got a clear board...'

A similar conversation was probably taking place in the cab of the express train's locomotive, very possibly at almost the exact same time. Farr's fireman had most likely also spotted the smoke from the excursion train's locomotive, and had turned and called 'Ed we got a train on the West Jersey tracks!' across the cab, to be told something to the effect of 'He should be stopping for us...we've got the clear track inbound'.

And this is where things really began to go south. Ed Farr may not have seen the first semaphore...the 'Distant' signal... set to 'Caution' because the express may have already passed it before Hauser reset them. Even so he still had to pass the intermediate and home signals, with the former set to 'Prepare to Stop', and the latter set to 'STOP'. and he should have seen them and, well, stopped. And here's where that ol' bugaboo, complacency rears it's ugly head.

Farr had probably been driving the express for at least a couple of years at this point, and he seldom if ever had to stop inbound. An inbound express train had the right of way at the crossing on two different levels...it was, well, inbound, and it was also a top priority train, one that other, lesser, trains yielded the right-of-way to.

Because he'd been driving the Express for so long, Ed Farr knew exactly where to start looking for the semaphore signals. In fact it was probably second nature. The problem is, though, he had almost never had to stop for them, so, well he didn't. He may not have even looked at the semaphores as he passed them. He could have just assumed that they would be set to give him the clear track ahead, so he didn't even slack up, roaring towards the crossing at around 45 MPH.

Meanwhile, totally against protocol as it may have been, Greiner did have a 'Clear Board'...the signals set to give him a clear track ahead. Seconds after he saw the semaphore, John Greiner was pulling the overhead-mounted throttle back towards him, opening the valve that sent steam to the cylinders, the locomotive's connecting rods flashing as the train accelerated toward its cruising speed of fifty or so Miles Per Hour.

As the excursion train hurtled towards the crossing, Greiner keeping an eye on the moving column of smoke marking the express train, watching as the locomotive, then the string of coaches following it became visible. Farr's eyebrows raised in puzzlement. Something wasn't right. The express was supposed to be easing to a stop. It was not supposed to be punching a smoke column skyward, connecting rods a blur as it bore down on the crossing at nearly fifty miles per hour. His eyes wide with horror, Greiner shouted, 'HE'S NOT STOPPING!!!, at first lunging for the brake handle before realizing it was futile...the crossing was less than a hundred feet away. They were pounding across it before Greiner could even grab the brake handle.

In the cab of the Reading train, Ed Farr's fireman went bug-eyed, possibly exclaiming 'What the hell is this guy doing'???' an instant before he very likely and very loudly yelled something like '...Big Hole her, Ed!!!!!'...Railroad speak for 'Emergency Stop NOW!!!!'. Ed Farr didn't take time to ask what was wrong...he just grabbed the brake handle and yanked it hard into 'emergency' with one hand while grabbing the 'Johnson Bar', as the reversing lever was known, on the right side of the cab, with the other and hauling it into 'reverse'. Even as he was struggling with the Johnson bar, Farr suddenly saw the West Jersey locomotive sweep into view less than 100 yards ahead of them, and even as the brakes dumped and steel wheels began singing against the rails, he knew with a horrifying certainty that they wouldn't even come close to stopping in time...

Greiner's first instinct when he saw the Reading locomotive bearing down on them was to jump. In fact he even stepped back from his seat to the rear of the footplate, between the cab and the tender, tensing to leap, looking up as he heard their wheels hit the crossing to see that the front of the onrushing Reading locomotive, fifty or so yards away, coming fast and looking as big as a house as it bore down on them. Greiner, realizing that his own locomotive, at least, would get clear, dived back into the cab. His locomotive and tender got clear...

*

.png) |

| For comparison purposes, a satellite view of the same approximate area shown in the area map above. The best part's the detail view, though. |

...But the first two passenger coaches didn't. The passengers seated on the right-hand side of the coaches saw what was coming. Some of them froze in terror, rooted to their seats while a few others dived out of their seats and scrambled for the vestibules, hoping to make it to coaches further back towards the end of the train. Not a one of them made it more than a few feet down the car's center aisle.

The Reading train was sliding. all wheels locked and singing against the rails, when its locomotive jack-hammered the first passenger coach just about broadside with a heart-stoppingly sudden, splintering 'CRUMP!!!', ripping through it almost lengthwise because of the crossing's extreme angle. The wooden coach came apart like a hammer-hit eggshell, splitting almost in two and leaving part of its sidewall draped across the locomotive's cab as it was kicked to the left, spinning clockwise and dragging the second coach off of the rails as it derailed violently. Almost all of the passengers in this first coach were ejected, either in the initial crash or as the shattered remains of the coach flipped and rolled, tossing passengers and wreckage in its wake, tumbling across the road that paralleled the Reading tracks back in that era before finally careening into a water-filled ditch just south of the road.

The second coach, careening off of the West Jersey tracks at an angle, slammed hard into left side of the Reading locomotive's cab. Slamming into the first West Jersy coach at an angle and over-running wreckage from it had already thrown the front end of the locomotive to the right and off of the track, and this second impact finished the job... The derailing locomotive, probably still moving at a good 35 to 40MPH, dragged its tender and the train's first coach off the rails before slamming over onto its right side, spinning, and sliding, digging a trench in the marshy soil between the Reading tracks and the road, tossing dirt-clods and mud curtains aside as it slid, shuddering to a stop with part of the first West Jersey coach lying across its cab. Farr and his fireman were both ejected as the locomotive flipped. Farr ended up partially beneath the locomotive, his fireman was nearby, mortally injured.

Even as the Reading locomotive slammed over and slid, its derailing tender pummeled the second West Jersey coach, already crushed for a quarter of its length, into kindling. The shattered coach derailed to the right, its shattered remains caroming across the road, shedding parts and passengers as it went. It's wreckage, no longer even vaguely resembling a railroad car, probably ended up partially on the road, blocking it.

The Reading train's first coach followed the locomotive and tender off the rails, bouncing across the West Jersey tracks, at the same instant the excursion train's still rolling third coach, which had ripped free of the second coach during the collision and derailment, reached the crossing. The excursion train's third coach probably broadsided the Reading coach, almost stopping short, definitely stopping quickly enough for the fourth coach to keep coming, over-ride it's coupler, and violently telescope the third coach, forcing its way a good quarter to a third of the way inside of it, brutally crushing and maiming passengers and smashing both cars into kindling while it was at it.

The Reading coach slammed over on its side, probably rotating even as it slid...inside, passengers tumbled from seats and bounced around the interior, pin-balling off of seats, walls, and each other like pocket change in a dryer for seconds that seemed like hours, before the shattered car shuddered to a stop, injuring nearly everyone on board and killing at least two.

The last three cars of the excursion train were still on the track and still rolling when they slammed into the fast-growing mound of debris directly ahead of them...the fifth coach overrode it's coupling and slammed hard into the fourth, crushing the vestibules of both as it came up short, but thankfully these three cars had lost enough momentum that they didn't telescope each other. The sixth and seventh coaches probably kept coming, possibly derailing and jackknifing at the same time the remainder of the express plowed into the wreckage fouling the crossing. The express train...or what was left of it...may have derailed as well. Then for a few seconds everything was, relatively at any rate, quiet.

The vestibules of the third and fourth cars of the excursion trains were blocked, so those passengers who could climb from the windows did so, dropping to the marshy ground. Parents lowered their kids out of the windows then climbed down themselves. Able-bodied passengers in the overturned Reading coach pulled themselves up and out through the windows on the high side, which had become skylights. Dads helped kids to climb onto the side of the car, told them to stay put, then helped wives to climb out before pulling themselves out and helping their families climb to the ground. Several passengers were able to escape in this manner...but several more were still inside the shattered coach, injured or worse

The second through last cars of the express train weren't as badly damaged as the excursion cars, and those passengers began climbing down from the platforms. Cries for help and moans were drifting out of the wreckage of the excursion train's first four cars and the express train's first car, and the uninjured and lesser-injured passengers made their way to the crushed cars and began working on rescuing trapped passengers. At least, they were thinking, it can't get any worse.

Except, it absolutely could...and did. Dozens of passengers were still trapped in the wreckage, and several dozen more were either on or in the coaches, trying desperately to disentangle the trapped passengers, or standing around, 'supervising', the entire scene backdropped by an eerie, all-encompassing roaring squeal as steam escaped from the overturned Reading locomotive's damaged boiler. No one gave it a second thought...The hissing roar of steam locomotive relief valves venting was a common sound.

Except this boiler was not only damaged, but catastrophically damaged in the crash, and in an instant frozen in the survivors' memories forever, the damaged seam let go with an ear-shattering roar, sending a thunderhead of condensing steam skyward and, far worse, spraying the trapped passengers and their would-be rescuers with high-pressure superheated steam and water. One second, they were straining and grunting, pulling at debris and lifting it away from trapped passengers, or standing on the gravel and earth embankment that the tracks and road were built on, the next second those grunts of effort became shrieks of agony as they were suddenly enveloped in a seemingly white-hot steam cloud while scalding sheets of super-heated water flayed away their skin. Dozens of passengers who had survived the crash...some relatively unscathed...were either scalded to death or critically burned.

News of the accident reached Atlantic City quickly! Hauser probably telegraphed the first report of the crash in almost as soon as it happened, and train-parts were very likely still bouncing and tumbling when he pounded out the first frantic dots and dashes. The citizens of Atlantic City, however, learned of the crash almost as quickly, and far more graphically. They probably first heard either the crash itself, or the Reading loco's boiler exploding, then saw that huge, boiling column of steam surging skyward. This steam cloud attracted first attention, then curiosity, then horrified realization. Atlantic City's citizens didn't know for sure exactly what had happened, but they knew something had happened, and whatever it was, it was bad. They started heading for the scene, singly and in small groups at first, then, as more detailed information filtered back to the city, in droves.

Reaching the accident was actually pretty easy back in the day. A drawbridge carried the Pleasantville and Atlantic City Turnpike across the Thoroughfare just south of the Reading and West Jersey RR drawbridges. After crossing The Thoroughfare, the road slanted northwest for about a half mile before swinging into a sharp left-hand curve and paralleling the Reading tracks all the way to, and beyond the scene, ironically very likely crossing the West Jersey tracks at a grade crossing just beyond the scene. From the looks of things, the present-day Atlantic City Expressway follows just about the exact same route as the former turnpike from that left-hand curve westward for at least several miles.

Within a half hour or less of the crash traffic between the drawbridge and the accident scene was every bit as crowded as modern beachbound holiday weekend traffic ever dares to get, with what was said to be thousands of people on foot and horseback moving among and around every form of horse drawn vehicle imaginable. Once they arrived, these citizens found a scene that was just about as horrible as it gets.

When the Reading locomotive slammed into the West Jersey train's first coach, it all but tore it apart, literally smashing through the wooden car lengthwise before bunting it into the ditch. More than a dozen passengers were killed instantly in the collision, and several of them were literally torn apart as the locomotive ripped through the car. Other passengers were violently ejected from the shattered coach as it flipped across the road and landed in the ditch.

First arriving rescuers (And spectators...a slew of the Atlantic City residents who journeyed to the scene did so out of curiosity) ran up on a mound of wreckage blocking the turnpike, crowds of passengers...both slightly injured and uninjured...pulling them towards the moans and pain-filled cries coming from said wreckage, and bodies all over the scene, some horribly injured, others already very obviously dead.

With growing horror, these same rescuers (And spectators) realized that some of the smaller pieces of wreckage were actually body parts. Swallowing both horror and nausea, many of the men climbed into the wreckage, trying to disentangle and extricate the trapped passengers. Freeing some of them was relatively easy, involving simply lifting them and carrying them out of the wrecked cars. Others required more work.

You have to remember that this was 1896, decades before even the most basic mechanical rescue tools were introduced. While many of the passengers had self-extricated, at least a couple of dozen of the injured passengers were in those first four West Jersey coaches. Anyone still inside the first two were probably already dead, but well over a dozen more people were likely still trapped in the telescoped third and fourth coaches as well as the overturned Reading coach. With only hand tools, probably from either the intact Reading coaches or the undamaged West Jersey locomotive (Both passenger trains as well as locomotives and cabooses carried a variety of rescue tools...prybars and hand saws...back in the day.) they started prying and pulling and cutting to free the trapped passengers. They had their work cut out for them, most especially in the telescoped coaches.

One account I read while researching this one spoke of 'The roof of one car being ripped off and dropping into the car on top of them'...that almost had to be the third coach, and rescuers who made their way inside found an absolute horror. Passengers in the about a third or so of the third coach...the distance that the fourth coach had forced its way inside of it...were crushed to death, probably accounting for at least a quarter of the fatalities, but there were also passengers trapped beneath the car's collapsed roof, as well as other passengers trapped inside the shattered coach. Many of the trapped, injured passengers were women and kids, and the rescuers did their best to comfort the frightened victims as they employed brute strength to lift and pry the broken car away from them.

The same thing was going on in the overturned Reading coach, which had probably been pile-drived by the still-moving third West Jersey coach before overturning. The Reading coach wasn't as badly damaged as the telescoped West Jersey coaches, but it presented another rescue problem...the make-do rescuers had to remove the victims through the windows, or possibly the now horizontal doors on the ends of the cars. This would have been a difficult and involved technical rescue operation today, even with modern equipment and training. A hundred and twenty-three years ago, without either, it would have been a nightmare.

Even worse, many of the passengers in all of the wrecked coaches had been horribly burned when the boiler exploded and were screaming in agony whenever anyone so much as touched then. When lifted, their skin and flesh sloughed from their bodies, and many of them were all but insane from pain. Most of the burn victims who were still alive when the rescuers arrived wouldn't live another 24 hours.

As several crews worked to free the trapped passengers, another group of rescuers moved among the bodies of the passengers who had been ejected, looking for signs of life and finding that many of these people were, amazingly, alive. Many of them horribly injured, some of them also burned, but alive. Rescuers started moving them to the embankment, probably between the road and the track, separating the still live victims from the deceased while they were at it.

Greiner and his fireman both survived with few if any injuries, but Farr and his fireman weren't so lucky. Both were ejected as the locomotive rolled and slid, with the fireman found either gravely injured or dead near the wrecked locomotive, and Farr dead, his body trapped beneath the locomotive's drive wheels and running gear. While the fireman's body was recoverable, removal of Farr's body would have to wait until a heavy wrecking crane could lift the wrecked locomotive.

In the tower, Hauser was busier than the oft-noted one-armed-paper-hanger. Telegraph wires were humming, and one of the very first things that he probably did, hard on the heels of the crash, was pounding out urgent messages to stations west of the scene stopping all traffic into Atlantic City on both the Reading and the West Jersey tracks. Once he confirmed that it was a major accident, with multiple injuries and deaths, another message was sent to Atlantic City Hospital, on the oceanfront, to tell them to get ready for an influx of patients. When the hospital received that message, calls went out for every doctor in Atlantic City to head for either the hospital or to the scene.

By 1896, the era of sending a rider on a fast horse to deliver these messages and requests had, thankfully, ended. The telegraph took care of the inter-station messages such as the urgent order to stop traffic, but I have a sneaking suspicion that most of the local messages were sent and handled quickly and relatively smoothly, thanks to Alex G. Bell's little invention. The telephone had become a common tool in businesses by the end of the 19th Century. There were somewhere around 250,000 telephones in use nationally by 1896, with the number growing quickly. Most were in either businesses or government offices, and I can just about bet that Atlantic City's hospital, hotels, and major businesses such as railroad offices had phones to communicate at least locally.

Meanwhile, as those notifications were being made, anyone who had brought a wagon to the scene was recruited as a make-do ambulance driver, and said wagons were maneuvered in as close to the scene as possible, the first group of patients were loaded, and these make-shift ambulances headed back for the city. There would be, very literally, dozens more patients to follow, suffering the gamut of injuries, from lacerations and contusions to massive, unsurvivable trauma. Six of these injured patients would die before morning, two more would die with-in the next few day, bumping the total number of fatalities to at least fifty.

While those patients were being loaded aboard the makeshift ambulances and some rescuers continued to search for injures passengers, others rolled up their sleeves and started the macabre task of body recovery, gathering the bodies they could access and recover, then laying them out on the embankment and covering them, often with newspapers, to await transport to a temporary morgue when one was set up an hour or two into the incident. Other hardy (and strong-stomached) individuals started gathering the body parts that were scattered around the scene and piling them in one place, while another group began collecting personal belongings, and piling them in another spot.

As these volunteer rescuers removed trapped passengers, loaded the injured onto wagons, and collected bodies, they realized that they were running into another problem...it was getting dark. The crash happened around 6:50 PM. This was long before 'Daylight Time' came into being, so by about 7:15 the sun was already dropping below the tree line and daylight was fast slipping away. Decently powerful portable scene lights and the generators needed to power them just plain long didn't exist yet and wouldn't for about a quarter century or so.

They may not have had lights, but they did have a lot of wooden debris. Men gathered wreckage from the wooden coaches, piled it high in a couple of strategic locations, and lit it off to provide light. These bonfires gave them light, after a fashion at any rate, but they also had to have given the already macabre scene an even more eerie, Dante-esque atmosphere.

They were going to need the light from the bonfires, because they weren't finished by a long shot. There were still passengers, living and dead, trapped in the wrecked coaches. They had made pretty amazing progress in the first hour or so of the incident, though, especially considering this was a group of 'civilians' and not an organized emergency response team of any kind, and that they were working with, at the most, hand tools. With darkness falling and flames dancing high into the hot night, they continued their efforts, now bathed in the flickering orange glow from the bonfires.

Even as all of this was happening, the investigation into the accident was kicked into gear by the arrival of Coroner William McLaughlin, who headed for the scene as soon as he got word of the accident. It's unknown just how soon into the incident he got there, but I believe it was fairly early on, possibly even before the bonfires were lit. He probably gave the wreck a quick 360...or as much of a 360 as was possible...when he arrived and may or may not have found and questioned John Greiner and his fireman while he was at it. We do know for sure that he went to the tower very shortly after he got there, bailed up the outside stairway, entered the tower, and probably started questioning Hauser almost before the door slammed closed.

He probably asked what happened first, and in answer Houser equally likely told him something to the effect of 'The West Jersey Excursion train had the clear track, and the Express ran the signal and hit it'. Mclaughlin's mouth probably dropped open upon hearing this. He was likely aware of railroad protocol as well as the fact that Hauser's actions busted it wide open, and when Hauser saw his look of disapproving surprise, he insisted that he set the signals to favor the excursion train because he thought it had time to clear the crossing. McLaughlin's very next question would...or at least should...have been something to the effect of. 'I don't care how much time you thought the West Jersey train had, why did you bust protocol bigtime by giving it a clear track'...but that question wouldn't get asked, at least not right then or right there.

Why? Because some things really haven't changed in a century and a quarter or so. The railroad was already in Damage Control mode. The phone was ringing, or the telegraph sounder was pounding out a message before McLaughlin could ask more than that first question, and when Hauser answered he was told in no uncertain terms not to answer any questions about the accident from anyone until he talked to the railroad brass.

When Hauser told McLaughlin that he couldn't answer any more questions. McLaughlin replied by having him arrested pending an investigation and transported to the Atlantic City jail. Hauser immediately posted a $500 bond...almost $17,000 in 2022 dollars...and likely went home to await the empanelment of a Coroner's Jury (And very possibly to pour himself a strong drink).

After Hauser was arrested, though, they probably have had another problem. The tower was more than likely being used as the on-scene command post, so they needed someone who was telegraph-qualified. Of course, it's a good bet that it also had a telephone by 1896, which would have simplified things greatly. Whatever they were going to do to take care of this sudden communications gap needed to be done quickly (And apparently, was), because as the rescues were in progress and the investigation starting, city officials in Atlantic City weren't just sitting on their hands.

While Atlantic City didn't have a paid fire department yet...fire protection was provided by nine volunteer companies until a salaried department was organized in1904...they did have a director of Public Safety, a gent by the name of James Hoyt, who had also been notified early in the ball game, He set up a command post (Probably at City Hall), probably grabbed a few other city officials to give him a hand, and they collectively rolled up their sleeves and dived right into the action.

It had quickly become obvious that this was a horribly grisly scene, with multiple fatalities, and one of the first things they needed to do was set up a morgue. The old Excursion House hotel, on Mississippi Ave at the oceanfront, hard by the turnpike, was chosen as the site for the morgue, probably due to its location and the fact that it may have been vacant at the time. Word was relayed to the scene (To the tower), probably by telephone, to have all of the bodies transported there.

While they were at it they needed to simplify the transport of both the injured and bodies. A call was made to Atlantic City's central rail terminal, and Hoyt told them he needed a couple of passenger cars and a locomotive. Preferably yesterday.

I'm not sure exactly how they did it, but I'm thinking that, if the last couple of West Jersey coaches were still on the track, a locomotive was backed to the scene and coupled to them, and those coaches would be used to shuttle both injured and dead, as well as the uninjured passengers from both trains, into the city. It would take a while to make that happen, though...up to a couple of hours if they didn't have an available locomotive with steam up.

If the West Jersey coaches were derailed, it would be longer still...not only would they have to find a locomotive and crew, they would also have to scare up a couple of passenger coaches. At any rate, they wouldn't be able to transport by railroad until at least a couple of hours into the incident, so at least half of the injured and many of the bodies were transported by wagon.

Meanwhile, the injured were arriving four or five at a time, in the backs of wagons, and all of them were going to Atlantic City's hospital. Atlantic City's then small hospital quickly became overwhelmed when thirty-plus patients, all badly injured, arrived with-in the first hour or so, a fact that Hoyt was quickly made aware of. He had a group start calling hotels near the Excursion House to ask if they could be used as temporary hospitals. The names of the hotels willing to do so were relayed to Hoyt at the command post, and he and his assistants put their heads together to brainstorm a game plan. One thing they absolutely needed to do was manage just how many patients were sent to each hotel.

They came up with a number, then probably either sent someone to the Atlantic City side of the turnpike drawbridge, or even more likely, recruited the bridge tender and had him intercept each wagon load of either patients or bodies and direct them to the proper destination. I have a feeling that the telephone helped out here as well. Once they decided how many patients would go to each hotel, they could keep tabs on how many patients were at each location, then advise the bridge tender where the next 'X' number of patients were to go.

Of course, once they got a locomotive and crew out to the scene, either with a couple spare coaches from Atlantic City, or coupled it to a West Jersey coach or two that was still on the rails, the remaining injured would arrive en-mass, and the operation of the drawbridge could be terminated. Of course this created a possible new problem...now they would have possibly dozens more patients arriving at once. They absolutely had to get the hotel-hospital operation ironed out and running smoothly before that happened.

The incident had probably been on-going for a good hour or so by the time the decisions concerning the morgue and using the hotels as temporary hospitals were made, but they were still short on one more important resource. Doctors. Every MD in Atlantic City, along, likely, with a few vacationing doctors who volunteered their services, were up to their elbows in seriously injured patients, with each doctor having several patients under his care. One of the local MDs probably told Jim Hoyt, in no uncertain word that they needed help. Big-time.

It wouldn't surprise me if Hoyt was given this information about the same time as the decision to use the hotels was made ('Jim, we're running out of doctors, here...'). Being director of Public Safety, Hoyt knew that the City of Philadelphia had a 'Emergency Corps', consisting of doctors who volunteered to respond to any major incidents with-in the states of Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, (A concept that was pretty ahead of its time in 1896!), and the incident probably wasn't more than a couple of hours old when he had a message telegraphed...or maybe even telephoned... to Philly, requesting the team's response.

Of course, the Emergency Corps members still had to be notified, and then they had to get them to the scene.

Today regional technical rescue teams and mass casualty response teams are alerted by pager, and can be deployed quickly, with multiple specialized vehicles hitting the road and heading for the scene, Federal-Q sirens screaming and Grover air horns braying, within minutes of the request.

Back in 1896 it wasn't that simple. While the doctors could be (Maybe) reached by telephone, they still had to be found and notified. Maybe...I'll even say probably...there was some kind of duty schedule that simplified things a bit, but getting the team rolling still probably wasn't exactly lightning-fast.

While our doctors were being notified, a train and train crew had to be made up. By 1896, train wrecks, sadly, had become commonplace, and railroads had emergency response down to an art form, with trains made up, coupled together, loaded with supplies such as stretchers, medical supplies, hand tools, and even heavy lifting jacks, and ready to roll...but a locomotive and crew had to be found and readied. Slowing things up a bit more in this particular case, our Emergency Corps members had to be found, gathered, and boarded.

Fifteen of Philly's Emergency Corps doctors answered the call, grabbed medical bags, and gathered at, I seriously suspect, the Camden and Atlantic City rail terminal across the Delaware River, in Camden, New Jersey, which also meant they had to get to Camden. And we have another problem...there wouldn't be a road bridge across the Delaware River to Camden for another thirty years. This meant that they would have to catch a ferry across the Delaware River first, then make their way to the Camden train station. Needless to say, this delayed their departure for Atlantic City even more.

The train bearing the Emergency Corps members didn't pull out of Camden until about 10:45 PM, probably, as I noted above, using the former Camden and Atlantic City tracks, (Which also meant that this was also West Jersey train, as the Camden and Atlantic was owned by the West Jersey by 1896 ) as they weren't blocked by wreckage. The locomotive heading up the rescue train, carrying only the doctors, would have only been pulling a couple of coaches, and would have had the highest priority. Every train between Philadelphia and Atlantic City would have been ordered to take a siding until the rescue train roared past, throttle wide open, probably running an honest 60 or so MPH.

That absolutely had to have been a hell of a ride. You have to keep in mind that in 1896, 60 MPH was an all but unheard-of speed, and running that fast at night would have been a thrill-park-level ride. The cars would have been rocking gently, but perceptively, the rapid-fire 'click-clack,click-clack,click-clack,' of wheels hitting rail joints making their speed all the more obvious. Our doctors would have been discussing the crash all the way in, wondering just what had happened as well as just what they were facing and what they would need, their hearts thumping with an adrenalin-fueled hyper awareness that emergency responders have felt untold millions of times over the passage of time.

All of them would probably been in one coach, and as they neared 'The Shore'...probably about the time they blew through Pleasantville, just under three miles from the scene...they would have moved to the right side of the car and started pressing their faces against windows. They would have spotted the orange-tinged smoke columns from the bonfires first, making them wonder if the wreckage was on fire until they passed the scene. Their eyes would have widened in shocked horror as they rolled past the scene and saw the wreckage, jumbled together and silhouetted by the fires, a horror image that would be indelibly embedded in their memories forever

I can almost bet that whoever was in the tower called the station to let them know 'The relief train just went through' as they passed the scene. They would have rolled into Atlantic City only five or so minutes later to find transportation waiting for them at the train station. By then, Hoyt and his crew had the city-end of the operation running like a Swiss watch, and they had already decided how many of our relief doctors would go to which locations...the only decision that needed to be made was just who was going where.

This was likely taken care of in a few minutes, and the horse drawn taxis or omnibuses that normally transported tourists now transported our doctors. They probably arrived in Atlantic City around 11:45 PM and were up to their armpits in patients by midnight or very shortly thereafter. To Atlantic City's overburdened MDs, they were about as welcome a sight as was possible. All of them would have a long long night.

The night would be equally long at the scene...most of the injured had probably been transported, either by wagon or train, by about 1AM, but there were still bodies that needed recovering, and a few of them...most notably Engineer Ed Farr's body...would have to await the arrival of a heavy wrecking crane. There were only twenty-nine bodies in the morgue by midnight, and body recovery went on through the night, with the last comparatively easily recovered bodies probably arriving at the temporary morgue sometime around sunrise the next morning. Forty-two bodies would ultimately be brought to the temporary morgue, with eight more dying at the hospital, bring ing the total numnber of fatalities to fifty.

The same train that had transported the injured and the bodies was likely also used to shuttle the uninjured passengers back to Atlantic City, where another special train would transport the uninjured excursion train passengers...along with thirty or so passengers whose injuries had been minor and who had already been discharged from the hospital... home. But it would take a while for that to happen as well.

The West Jersy tracks (As well as the Reading tracks) were still blocked. Both railroads, apparently, moved quickly to get the tracks cleared and repaired to the point that trains could run. working by firelight alongside the rescuers who were recovering bodies. The two groups just about had to be working on these two diverse tasks at the same time, because the West Jersey special train taking the uninjured excursion passengers back to Bridgeton left Atlantic City 'several hours' after the accident...I'm guessing around daybreak or a little before.

The first few minutes of that trip were probably about as traumatizing as it gets. The passengers first had to board another train at the very station where the fatal trip began, then ride along the exact same route, finally passing the scene, where the overturned and shattered Reading locomotive was on display for all to see, wreckage was piled high alongside the tracks, smoke was still rising from the bonfires, and people were still crawling around the ruins.

The scene was bad enough at night...daylight, however, revealed just how devastating the collision actually was. Of course, all of these people had experienced the collision firsthand the previous evening and were likely already traumatized. Passing the wreckage again just reinforced that trauma. On top of that the train probably had to creep past the scene at reduced speed. The tracks had been repaired, but this was likely a temporary repair, specifically to allow that particular train to pass, and to allow wrecking and recovery equipment access to the scene.

Coroner McLaughlin apparently didn't waste any time either...he had a Coroner's Jury empaneled by the afternoon of the next day (The 31st), though actual testimony apparently didn't get rolling for a couple of days. The most telling testimony came on August 4th, when John Greiner as well as several surviving passengers from both trains testified. The jury retired the next day and returned verdicts on August 7th. Greiner was all but cleared of fault, though the jury did note that he should have used more caution in crossing in front of the oncoming express train (Translated, I'm sure, to 'Knowing you were supposed to yield to the express, you should have slowed and prepared to stop, just in case.)

They really socked it to Ed Farr, who of course, wasn't able to defend himself. The jury noted that, in blowing through the crossing at 45-50 mph he ignored not one, but three signals...two set at caution, and the third to 'Stop'...a move that many found absolutely inexplicable, as he was well known as a very conscientious and safe engineer.

That old bugaboo, complacency, just may have been the culprit...the afternoon express had the right-of-way on two different levels. It was inbound and it had priority other trains going in either direction unless train orders demanded otherwise, so it was a fair to good bet that he just assumed he had the right-of-way...something he may have done multiple times in the past. It's a more than plausible theory, and the one I subscribe to (As if I'm some kind of expert or something).

There's one little problem with that theory, though...he had stopped, while inbound, on at least one other occasion, a fairly recent occasion at that, and that is what had people scratching their heads. Again, Farr was not known to be a reckless engineer. A few people theorized that he had possibly suffered a heart attack or stroke just before reaching the signals, but if that had been the case, his fireman would have been aware that something was wrong and could have brought the train to a stop. As both Farr and his fireman were killed in the crash, it was a mystery that would remain unsolved.

Of course, blaming the Express' crew was also the easiest way to close the case, and let's be real here...what ever the reason, he is the one who blew through three signals set against him while the excursion train did have a clear track.. Ed Farr's actions were found to be the primary cause of the collision.

While they were at it, the Coroner's Jury also slammed George Hauser, noting that he used exceedingly poor judgement when he abandoned all protocol and gave the excursion train the clear signal. There was no mention, however, of what if any consequences he suffered because if the jury's verdict, though I can't help but wonder of he ended up losing his job over his error.

Whatever consequences he may have suffered, it couldn't bring back the fifty people, many of them women and children, who died in the crash, nor could it miraculously heal the dozens who suffered debilitating injuries. Most of the victims lived in Bridgeton, New Jersey and news of the crash probably hit the town the next morning with the arrival of the uninjured and slightly injured passengers. Needless to say, family members of the doomed beach-goers wo didn't return to Bridgeton freaked, leading to an influx of worried family members who fell upon Atlantic City, but I suspect they had to wait a day or so.

Once the special train taking the uninjured excursionists home had passed the scene the tracks were probably blocked for several more hours as the big steam-powered wrecking crane righted and removed the Reading Locomotive, and Ed Farr's body was recovered. Then permanent repairs had to be made to the damaged tracks, which could have taken another day or so, so it could have well been August 1st or even 2nd before any other trains could pass the scene.

Once those repairs were completed, the family members of the deceased and injured fell upon Atlantic City, some to visit their injured relatives, and others to search for missing loved ones, many of whose bodies still hadn't been identified a couple of days after the accident. I couldn't find much information at all about this phase of the incident, but it couldn't have been even vaguely pleasant for either those manning the temporary morgue, or family members searching for loved ones. Many of the bodies were dismembered and mutilated beyond recognition, several were horribly burned by the steam from the boiler explosion, and in some cases identification was likely all but impossible.

On top of that, remember that this was in the middle of the Summer...Residents of any given U.S. East Coast beach city will tell you that their hometown is among the hottest places on earth during the summer. These bodies were sitting for a couple of days before they were identified and released to family members, or possibly released for burial in a mass grave (Which is what was done with the body parts that were recovered from the scene). The inside of the old Excursion House absolutely couldn't have been a pleasant place to be.

Then, of course, once the bodies were identified, the surviving relatives had to arrange for transport back to Bridgeton, where funerals probably seemed to go on forever during that first week of August, 1896. Many of these funerals were especially tragic because...as is often the case in accidents such as this...many families lost multiple children, several families lost both parents, and a couple of families were wiped out entirely.

Sadly, there doesn't seem to be any memorial to the fifty victims of the crash, which actually seems to have flown under the radar, largely because it was overshadowed ten years and change later by another deadly crash, also in Atlantic City, on the same railroad.

But it hasn't been entirely forgotten. The headstones of the victims still exist in Bridgeton, of course, and descendants of some of the victims still live there At least one of them has memorialized their distant, deceased relatives in a blog post, which I'll include in 'Links'

I always find it sad when victims go unmemorialized...these people left Bridgton that long ago July morning for a day at the beach, as millions of families have done over the last century and a half or so. Unfortunately, their day ended in a scene of absolute horror. Hopefully this post will help keep them from being forgotten.

<***> Notes, Links, And Stuff <***>

When an incident occurred a century and a quarter ago and isn't all that well known in the first place, I'm not exactly surprised when I can't find all that much information about it. In fact, I'm more surprised when I find any usable information...much less an actual abundance of it...about any obscure or semi-obscure incident, especially one that occurred over a century ago

That being said, when you've got a run of good luck going, you need to run with it. The 'Good Luck' I'm speaking of here is finding really good information sources for a post about a less than well known incident, even though few such sources actually exist. For the second post in a row, all of the links I found were good, solid links packed with useful information, even though there were only about four or five of them...the inevitable Wiki article, a pair of blog posts, a reprint of a newspaper article, and even a photo of the scene, taken the next morning.

And the good luck just kept on rolling in...what I believe to be the old right of way for the long-gone West Jersey and Seashore R.R. still exists, now utilized as a power line right-of-way, and clearly visible on Google Maps' satellite view.. You can...I think...even see where the old diamond crossing used to be, as the present-day NJT rail line into Atlantic city lies on the former Reading right-of-way. Of course, and maybe even inevitably, this happy find refuted a bit of the info I already had, as the description of the approach to the crossing in one of the blog posts I found and the way the crossing was actually laid out were two entirely different animals.

Still, with the quintet of good links, and the google maps satellite image of the old West Jersey right of way backing me up, I had a good solid base to start building this one on. Oh, there were a few more little bumps in the road...but they also added a bit of a challenge to the process and made it more fun to write. The afore-mentioned discovery of the old West Jersey right-of-way caused me to have to rework a few paragraphs. There was no real description of exactly how the crossing and tower were positioned in relation to each other or, even more importantly, exactly where the wrecked cars and locomotive ended up in relation to the crossing and each other. (That one scene photo helped immensely here...and contradicted the way I thought the Reading locomotive and the excursion train's cars landed while it was at it, causing me to have to make a couple more 'on the fly' changes), . Oh...the use of the telephone was pure speculation on my part...but I'm also pretty sure that one was right on the money (I'll look at why in one of the 'Notes'.)

Ineitably, I ran up a bit of contradictory info here and there. One good example's the name of the tower operator...he was identified as both George Hauser and William Thurlow....Hauser was the name that appeared most frequently, while Thurlow's name appeared only once, so I went with the most popular choice.

There was even a fair amount of detail concerning just what went on at what had to have been an unbelievably chaotic scene, but still not enough to keep me from filling in the blanks, so to speak, with what I think may have happened. Obviously, for example, I have no idea what conversations actually took place in the locomotive cabs or in the tower, but I think (Ok, hope) I made some pretty good guesses. I have no clue what went through the heads of James Hoyt and his crew as they did what can only be described as an outstanding job of getting things organized in Atlantic City, nor do I truly know how or when during the incident's time line anything happened, so I had to sort of read (And write, for that matter) between the lines a bit and hope that the way I think things happened is at least close (Or, barring that, at least makes sense) .

I also had to do a bit of guess work to figure out just how the West Jersey and Reading lines were actually situated as well, even with the West Jersey right-of-way still visible. In fact, that may have been the biggest guess of not only this post, but possibly of this entire blog so far.

The West Jersey line the wreck occurred on was described in one of blog posts I used for reference as running parallel to and between the former Camden & Atlantic and the Reading tracks until they reached the fatal crossing, but here's the thing...the former Camden & Atlantic was actually a subsidiary of the West Jersey in 1896 (Also making it, like the West Jersey, part of the ginormous Pennsylvania Railroad system).

The West Jersey was actually a pretty comprehensive system in 1896, comprising nearly 800 miles of track (Counting yard leads and sidings), with several long branch lines. If not for the fact that the blog post I just mentioned distinctly mentioned the West Jersey running parallel to and between the former C&A and the Reading, I would have wondered if the West Jersey right of way and the former C&A right of way were one and the same, with the branch line leading to Bridgeton actually branching off of the old C&A right of way at a turn-out (What non-railfans call a 'switch). And a tiny part of me still wonders if that was the case. The thing that puzzles me is the fact that the old C&A right of way is completely gone, though it does appear on some old topo maps (But the fatal diamond crossing doesn't, adding a bit more confusion to the mix)

So, after squinting at said maps and the satellite view meaningfully and at length I ended up writing it the way it seems to have happened, according to the descriptions I read, and the layout of the old right of way and what may be the location of the diamond crossing...I tried to get it close to right. That being said, as always, any errors are mine and mine alone, and anyone with better, more accurate information, please feel free to speak up. I hope I at least came close to being accurate, and while I was at it, I hope I made this post informative, interesting, and a good read.

On to the 'Notes'!

<***>

Not only was Edward Farr's death one of the most horrible out of the fifty deaths caused by the wreck, his death also caused one of the weirdest incidents of the whole event.

Farr was ejected from the cab of the Reading locomotive as it flipped on its side and slid, and he somehow apparently ended up beneath one of the big drive wheels, pinned between it and the ground. At least when the boiler exploded, he was probably already dead, because he would have been just about at ground zero when the huge burst of superheated steam and water blasted out of the boiler. Because his body was trapped beneath the overturned locomotive, it was also one of the last, if not the last to be recovered, probably the next morning.

Farr was also married, and his wife was likely notified of his death the next day, maybe even before her husband's body was removed from the scene. I believe the Farrs lived in Philadelphia, and his wife was probably notified of his death by Reading railroad officials. Several news articles reported that, upon hearing of her husband's death, Mrs. Farr 'Fell to the floor, dead'...likely suffering a fatal heart attack.

Then, a couple of days later, no less than the New York Times reported that Mrs. Farr attended her husband's funeral, and even gave a statement to the paper that she was 'absolutely devastated' by her husband's death.

Either the reports of her death were false news, meant to further sensationalize the wreck (Not all that improbable, as news reports in that era tended to be far more graphic and sensational than they are today) or, in an even weirder twist, someone impersonated her at her husband's funeral.

Either way, it just added a surreal bit of weirdness to an already immensely tragic accident.

<***>

While none of Atlantic City's fire companies responded to the scene, I can just about bet that some of the city's firefighters were among the huge crowd of citizens who responded to the crash. I can also just about guarantee that when they got to the scene, they dived in with both feet and went right to work. It also wouldn't surprise me if they were a large part of the reason that operations at the scene were handled with at least a suggestion of organization.

In 1896, Atlantic City's nine volunteer fire companies had well over a dozen huge frame hotels to protect as well as hundreds of smaller businesses, a few hundred private dwellings, and miles of boardwalk, so they had their share of incidents in any given year. The fact that this largely wooden city was still standing attests to their skill. These guys knew what they were doing.

And, judging from their stations, several of which were utilized by the salaried A.C.F.D. until well into the late 20th Century, these weren't impoverished fire companies running ancient equipment out of lean-to sheds. These were well financed, well equipped fire companies. Their guys were seasoned firefighters, their officers experienced in taking the chaos of a fire scene, and whipping it into order, and all of them were well acquainted with handling large, chaotic emergency scenes. And I have a feeling that the first several firefighters arriving on scene on scene did just that.

I also wouldn't be surprised if some of them weren't on the way to the scene as soon as they saw that column of steam boiling skyward, and when they got there, they dived right in and assisted in the rescues. I'm going to go out on a limb and say that word may have even been sent back for extra hand tools...axes and prybars...from the city's single truck company (The truck itself, being both horse drawn and the only ladder company in the city, most likely wouldn't have responded).

While firefighting and rescue in 1896 and 2022 are entire universes apart in many ways, the basics haven't changed. On a major accident scene, you locate your patients, you gain access to them, you disentangle them, you extricate them, and you transport them. From the sounds of things, the crowd gathered around that pile of wreckage a mile or so east of Atlantic City did just that. And, again, I have a sneaking suspicion that a few dozen members of Atlantic City's fire companies are a big part of the reason the operation went as smoothly as it did.

<***>

Ahhh, the telephone! When I stated that the telephone very possibly sped up and smoothed out communications, it was speculation, but it was speculation that had a few facts along to back it up.